If you’ve met me, firstly I apologise, and secondly it’ll come as no surprise that I have a tendency to ruminate on that which many others pass over without so much as a backward glance. Previously this resulted in me writing something in the region of 25,000 words on the Knox Decalogue, and today I’m going to turn my eye upon the Haycraft-Queen Cornerstones list. Prepare thyself…

Continue readingInverted Mystery

#859: “You’re a wicked man to be thinking such things…” – Shooting Script and Other Mysteries [ss] (2021) by William Link and Richard Levinson [ed. Joseph Goodrich]

William Link and Richard Levinson are undoubtedly best known today for their work done in creating TV crime-fighters Lieutenant Columbo, Jessica Fletcher, Joe Mannix, and Alexander and Leonard Blacke, as well as for a host of guest writing spots on other classic crime shows from the 1950s onwards. Shooting Script and Other Mysteries (2021) collects 17 stories by the pair that were published over a period of twelve years, mostly in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine.

Continue reading#858: The Bride Wore Black, a.k.a. Beware the Lady (1940) by Cornell Woolrich

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Past Jim has a lot to answer for — this haircut, for one, or that fact that I cannot forget the embarrassment of 11:48am on 4th June 1997 — but my current frustration with him is how easily and summarily he dismissed the writing of Cornell Woolrich after reading the Nightwebs (1971) collection as part of the Orion Crime Masterworks series. Had Past Jim possessed a little more discernment (or, dare I say it, maturity), I could have been loving Woolrich’s work for the last two decades instead of coming to it so late. Yes, I got here eventually, via some short stories, some novellas, and a couple of American Mystery Classics reissues, but what is life without something to lament?

#813: “French was close to the truth, hideously, damnably close…” – The 9.50 Up Express [ss] (2020) by Freeman Wills Crofts [ed. Tony Medawar]

I know what you’ve been thinking: “For such an apparently avowed fan of Freeman Wills Crofts, that Invisible Event guy hasn’t exactly jumped on the recent collection from Crippen & Landru…”. Well checkmate, my friend. Check. Mate.

Continue reading#780: Come, Tell Me How You Live – Repudiation in Narration via Murder Isn’t Easy (1936) by Richard Hull

The first time I ever emailed an author, it was to enquire of Harlan Coben why he’d opted in Tell No One (2001) to switch between first- and third-person narrative in the telling of a story that, to my callow, untutored eye, could have told throughout in third person. I phrased it more politely than that, but you get the gist.

Continue readingIn GAD We Trust – Episode 20: The Dr. Thorndyke Stories of R. Austin Freeman [w’ Dolores Gordon-Smith]

In January of last year, I read my first R. Austin Freeman novel, little suspecting that it was to be the first step along a road of sheer delight. And so, to mark the end of Series 2 of In GAD We Trust, today I’m discussing Freeman and the Thorndyke stories with author and fellow R.A.F. fan Dolores Gordon-Smith.

Continue reading#755: Mystery on Southampton Water, a.k.a. Crime on the Solent (1934) by Freeman Wills Crofts

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

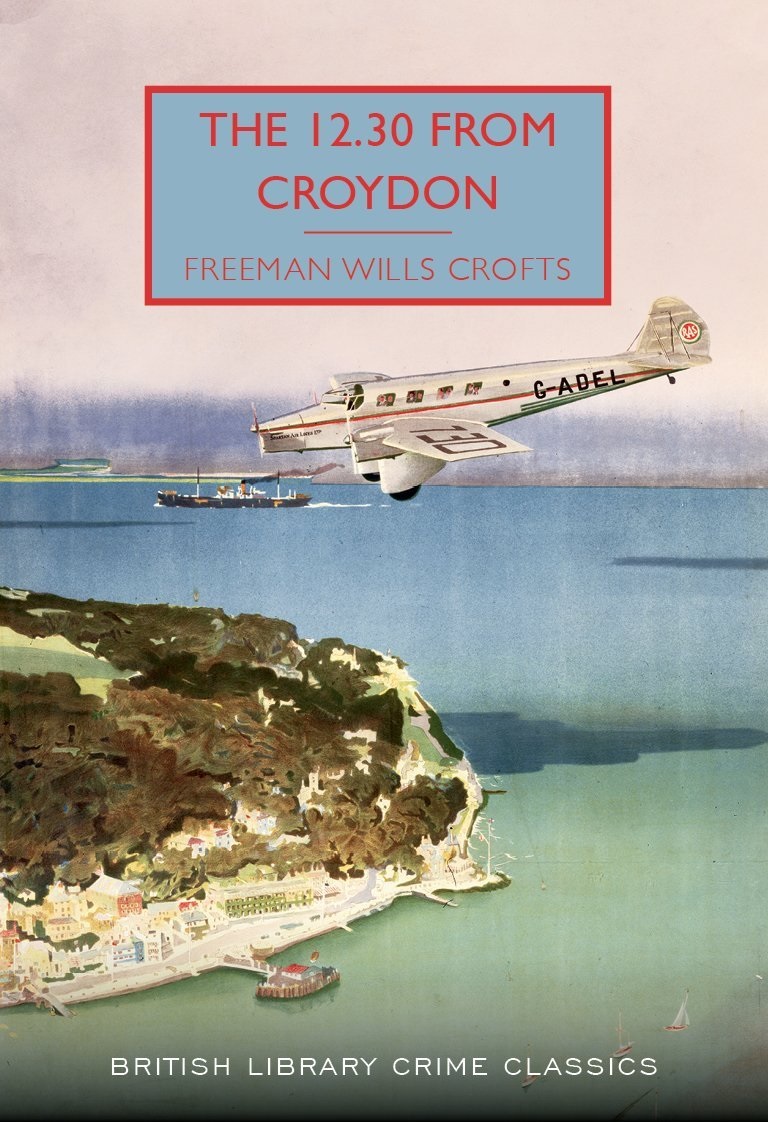

For evidence of the restless enthusiasm Freeman Wills Crofts brought to the writing of detective fiction, look no further than the two books he published in 1934. The first — The 12.30 from Croydon, a.k.a. Wilful and Premeditated — was his first inverted mystery, a fairly standard affair in which we are wise to the killer’s reasons, actions, and thoughts from the beginning and which Inspector Joseph French then unpicks quickly in the closing chapters. No doubt Crofts was interested in this new form, but simply repeating a formula which, if we’re honest, gets a little bit long-winded in the closing stages did not appeal. And so changes were wrought for a second stab.

#724: The 12.30 from Croydon, a.k.a. Wilful and Premeditated (1934) by Freeman Wills Crofts

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The writing of an inverted mystery must surely bring with it a certain amount of release. Your typical detective novel, after all, keeps the villain, their motives, their opportunity, and oftentimes their method occluded from the reader whilst ideally also dropping all manner of subtle hints about them, where the inverted mystery — in which we know the criminal and their motivation from the off, see the crime committed, and must then watch the detective figure it out — removes every single one of these difficulties, requiring only the investigation which would have happened in a ‘straight’ novel of detection anyway.