Today is the fifth Bodies from the Library conference at the British Library where, at approximately 16:40 this afternoon, after the intelligent people have had their say, Dan and I shall take to the stage to discuss impossible crimes in fiction.

Other bloggers, whose reportage skills far outstrip my own, will doubtless reflect on the day once it’s done, so I wanted to instead give you a preview of sorts. Because one of the 40+ impossible crimes we’ll be talking about is the novella Mystery in Room 913, a.k.a. The Room with Something Wrong (1938) by Cornell Woolrich and, having read it several years ago and reread it in preparation for our talk, I thought I’d dig into it here in decidedly more depth than I’m going to be able to there.

First appearing in Detective Fiction Weekly #120 in 1938, Mystery in Room 913 is essentially a Room That Kills impossible crime story: at seemingly random intervals, when young men check in alone — “It only happens to singles. When there’s two in the room nothing ever happens” — to the eponymous room in the St. Anselm Hotel, they’re found in the early hours of the morning having leapt to their death from the French windows. The room does not discern beyond the fact that each person is alone when they die — as far as anyone can tell, these men are in good spirits when they arrive: whistling show tunes from comedy performances they’ve been to see, recently engaged, having an offer of work after too long unemployed following the ravages of the Great Depression…nothing in their make-up on conduct would imply suicide anywhere in their minds, and yet each dies and the house detective Striker becomes increasingly overwrought at the apparently casual attitude of the City detective Eddie Courlander who always seems to be the one sent when the calls get made:

“Here’s how these things go,” he said patronizingly. “No one got in there or went near him, so it wasn’t murder. He left a note, so it wasn’t an accident. The word they got for this is suicide. Now, y’got it?”

Oh, yeah, the notes: always brief and to the point, always found in the room when the detectives go up to inspect the scene, and to providing a no doubt solid basis for Courlander’s quick conclusions. Nevertheless, Striker isn’t happy:

He went back up to his own room again with a vague feeling of dissatisfaction, that wasn’t strong enough to do anything about, and yet that he couldn’t altogether throw off. Like the feeling you get when you’re working out a crossword puzzle and one of the words fills up the space satisfactorily, but doesn’t seem to have the required meaning called for in the solution.

I first read Woolrich as part of the Orion Crime Masterworks series and at that time his gloomy, Noir-tinged style of writing didn’t quite play up to what I wanted from my fiction. While not exactly predictable, there was something puckish in the gleeful inevitability of the stories in that collection: inevitability not of glee, you understand, but of the quite, underplayed misery that would seep around the edges of his prose, situations, and characters, the unashamed embrace of the mire of negative inevitability. All his stories from that collection seem now, in my faulty memory, to be possessed of the same demeanour — an assiduous commitment to the sort of negativity now best associated with Scandi writers and their paedophile-hunting alcoholic divorcee detectives who don’t phone their daughters and have a violent streak. Whether this is emblematic of Woolrich’s work overall or not I don’t know, but I doubt it: the guy wrote a lot of stuff, and maybe that collection was simply a deliberate attempt to find the more Noir-focussed writing.

I first read Woolrich as part of the Orion Crime Masterworks series and at that time his gloomy, Noir-tinged style of writing didn’t quite play up to what I wanted from my fiction. While not exactly predictable, there was something puckish in the gleeful inevitability of the stories in that collection: inevitability not of glee, you understand, but of the quite, underplayed misery that would seep around the edges of his prose, situations, and characters, the unashamed embrace of the mire of negative inevitability. All his stories from that collection seem now, in my faulty memory, to be possessed of the same demeanour — an assiduous commitment to the sort of negativity now best associated with Scandi writers and their paedophile-hunting alcoholic divorcee detectives who don’t phone their daughters and have a violent streak. Whether this is emblematic of Woolrich’s work overall or not I don’t know, but I doubt it: the guy wrote a lot of stuff, and maybe that collection was simply a deliberate attempt to find the more Noir-focussed writing.

Or maybe I’m misremembering. That happens a lot these days.

So when I first read Mystery in Room 913 I was surprised at how much it fitted into what seemed to me at the time to be the typical Golden Age pattern of things: an (essentially) amateur detective going his own way to prove a series of cleverly-disguised murders as just that. With the benefit of hindsight, I see now that this isn’t exactly typical Golden Age; indeed, there’s much more of a thriller aspect to it with its nervy searching of rooms and all-action finale, but I think I had a sense of it being a far more detection sort of tale on account of it providing a clue in a manner that, at the time, I felt quite smart for having spotted (at least in part because something else, a little more detection-oriented, had hidden a clue in a similar way and so I deemed that this was how clues were done in detective fiction…Naivety, thy name is Jim). Bear in mind that, for context, I’d read a bunch of Agatha Christie and then the likes of Dashiell Hammett, Jim Thompson, Margaret Millar, and Ross Thomas, and was still on a Harlan Coben, Robert Crais, and Michael Connelly kick…so I didn’t really know what I was talking about.

Coming back to this a second time, it’s amusing to see that Woolrich anticipates in two keys ways almost the entire plot of a John Dickson Carr novel that’s still a few years off whilst also paying…maybe ‘homage’ is too strong a word…to an Agatha Christie novel that had preceded this by a similar duration. There’s very little in the way of clewing in the way that I remember, just that one instance of screaming unsubtle bell-ringing that even 2003 Jim could spot, and there’s a key development at the end which I do not remember and which, alas, put a slightly bitter spin on this reacquaintance, but overall I enjoyed this the second time around: it’s superbly written, dark and light in all the right places, has a effortless sense of place — no doubt informed by Woolrich living in an hotel at the time of writing — and, perhaps most delightfully, is full of tiny character beats that really came to life under my older eyes.

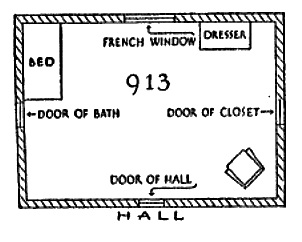

Also, there’s a floorplan!

In fact, there are two…but spoilers in the second.

As a more seasoned reader, I get a great deal more enjoyment from Miss Flobelle Heilbron, the “hatchet-faced, beady-eyed” denizen of room 911, who “seemed rather gratified at finding herself an object of attention, even in the middle of the night” following one of the suicides since “she couldn’t get anyone to listen to he most of the time” — captured beautifully in the complaint by the hotel manager Mr. Perry that “The building could be burning, and if we both landed in the same fireman’s net, she’d still roll over and complain to me about the service”. The Chinese-American lawyer Mr. Young and his nameless wife, considered to be ‘prestige’ guests on account of the money they possess which would allow them to stay at any number of other hotels, would no doubt delight Ronald Knox in Striker’s admission that “It’s because they’re Chinese that I was so ready to suspect them, They always seem sinister to the Occidental mind”…but then their Pekingese dog will whine at the apparent instigation of each murder… And then there’s Pete the Hermit in room 909 with his “mild blue eyes with something trusting and childlike about them” which speak volumes about the confidence tricksters who have sold him useless gold mines in Canada that he’s keen to discuss at every opportunity.

Now I see the genius in these thumbnail sketches, the canny weighing up of a person spotted in the corridors where Woolrich and his mother were making their home and then expanded just enough in his mind to be turned into fiction. Courlander himself is immediately marked out as a cop since “he couldn’t have looked at a dandelion without congenital suspicion”, and Perry summed up by his delight at the police refusing to see any suspicion in the deaths and so attach no bad name to his hotel. As the protagonist it’s perhaps to be expected that rather more can be said of Striker, and even as the only person to undergo any sort of change his development from a man who would much rather sit in bed and read “a crackling good super-science story” in his fiction magazines than get too involved in anything to being driven by the denial of those around him to get to a truth that only he can see is handled well.

The investigative sections of Striker’s transformation — submitting room 913 to an exacting search of all details not once but twice, even going so far as to pass a night in the room himself in order to confront the danger it represents — are balanced well against his legitimate personal interest in the well-being on those who stay there. The frank relief when the first couple to stay after one of the deaths leave the hotel after three days “perfectly unharmed and vowing they’d never enjoyed themselves as much in their lives” stands in blissful contrast to Striker’s 3am vigil with the hours ticking by “like drops of molten lead” as he waits with his nerves a-jangling to see if the newest occupant of the room with suffer the fate those French windows seem to rear up horribly in his mind as representing:

The investigative sections of Striker’s transformation — submitting room 913 to an exacting search of all details not once but twice, even going so far as to pass a night in the room himself in order to confront the danger it represents — are balanced well against his legitimate personal interest in the well-being on those who stay there. The frank relief when the first couple to stay after one of the deaths leave the hotel after three days “perfectly unharmed and vowing they’d never enjoyed themselves as much in their lives” stands in blissful contrast to Striker’s 3am vigil with the hours ticking by “like drops of molten lead” as he waits with his nerves a-jangling to see if the newest occupant of the room with suffer the fate those French windows seem to rear up horribly in his mind as representing:

He visualised it for the first time as a hungry, predatory maw, with an evil active intelligence of its own, swallowing the living beings the lingered too long within its reach… It looked like an upright, open black coffin there, against the cream-painted walls; all it needed was a silver handle at each end. Or like a symbolic Egyptian doorway to the land of the dead, with its severe proportions and pitch-black core and the hot, lazy air coming through it from the nether-world.

Jim

Good luck this afternoon. I’ll be rooting for you !

Nigel

LikeLike

Thanks, Nigel — it’s going to be a good day, always a highlight of my year. See you soon!

LikeLike

“Does anyone know of its inclusion in other anthologies? Because it doesn’t seem to be discussed much, and that’s a real shame.”

Douglas Greene included it in Death Locked In: An Anthology of Locked Room Stories and it made my list of favorite (short) impossible crime stories. I think it’s one of the best room-that-kills stories.

Remember to speak with religious fanaticism this afternoon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

He killed it, TomCat! You would have been proud! 🙂

LikeLike

Aw, hush 🙂

LikeLike

Yeah, it was the mention of this on your favourites list that spurred me to find it in the first place — indeed, I’m still working through that list to this day!

If anyone’s not seen TomCat’s two lists of favourite long- and short-form impossibilities, you can find the list of novels here and the short stories and novellas here. Some great suggestions there if you need any guidance on where to begin…

As for the religious fanaticism, I hope some of the enthusiasm Dan and I felt came across. The very first person I met at the conference told me that they weren’t really that sold on impossible crimes — even gave me their copies of Rim of the Pit and She Died a Lady, having found them a bit disappointing — and I didn’t get a chance to find out if they felt any different at the end…! Maybe they had a St Paul on the road to Damascus moment, or maybe they finally made peace with impossibilities simply not being their thing. I’ll take credit, either way 🙂

LikeLike

“Some great suggestions there if you need any guidance on where to begin…”

The lists need to be revised and updated, but glad they’re still being used to bloat people’s wish lists. As you work your way through those lists, you should give some priority to Robert Arthur’s “The Glass Bridge.” Xavier is the only one, besides me, who appears to have read that gem.

“The very first person I met at the conference told me that they weren’t really that sold on impossible crimes — even gave me their copies of Rim of the Pit and She Died a Lady, having found them a bit disappointing…”

Why didn’t you put this person to the sword?

LikeLike

As it happens, I did read ‘The Glass Bridge’ recently and will be writing about it next month — so stay tuned!

Why didn’t you put this person to the sword?

When you’re a speaker they give you a green name badge, and if I’d been identified as a murderer early on it may have made things awkward for our talk. I mean, sure, everyone there likes a good killing, but it still seemed a risky proposition… 😄

LikeLike

It’s a better than the tired old “a sword swallower ate my sword” excuse, I suppose.

“As it happens, I did read ‘The Glass Bridge’ recently and will be writing about it next month — so stay tuned!”

Excellent!

LikeLike

Have a good time at the Library!

I think you’re probably right that Woolrich has fallen a bit from view among crime-fiction readers. Of course, he most certainly hasn’t among film noir aficionados, for whom the knowledge that a movie’s based on a Woolrich tale is an immediate magnet.

LikeLike

My memories of Woolrich’s Noirish tendencies are vague, but I can see there’s a certain quality to his worldview that would lend itself to a type of classic cinema. Something between Hitchcock and HIBK, which handeled well could be very special.

Thanks for the kind word about Bodies, too. It was a great day, but then it always is.

LikeLike

Something between Hitchcock and HIBK, which handeled well could be very special.

Sort of like Rear Window, you mean?

LikeLike

Ha. Nice one.

LikeLike

It seems to be available on Kindle for a little over £2. Not exactly a ‘snip’ for seventy-odd pages but not too bad . Hope you had a good day.

LikeLike

Not a snip, no, but good money for a classic of the form. And it’s far too interesting a piece to dismiss, even if you don’t enjoy it. Snap it up!

LikeLike

Hope the event goes well – I am envious of all those attending and will look forward to reading all about it!

This work sounds really fun. My only taste of Woolrich so far was I Married A Dead Man which is, of course, an inverted story but I love the idea of this. I will clearly need to track down a copy for myself!

LikeLike

I love some of Woolrich’s titles, and I Married a Dead Man is just so redolent with possibility. I get the impression he wrote more in that sort of idiom than this one, but this is so good that I’d be tempted to “come across” to his more fervid setups and the sort of sweaty, EIRF-tinged prose I imagine him writing most of the rest of the time. The guy has a way with words, that’s undeniable.

LikeLike

This story, a great one, was also included in the William Irish anthology Somebody On the Phone (also published as Deadly Night Call), which also included Boy With Body, another classic Woolrich, as is Momentum. Room with Something Wrong also appeared in Ellery Queen magazine #79 (June, 1950), alongside Rex Stout, Q. Patrick, and Stuart Palmer–quite a lineup!

LikeLike

It’s always fascinating to me to see the covers of the old EQMMs and consider the wealth of talent that appeared in certain issues…and that’s just the names on the cover! While I’m sure a great many talented authors are writing for it today, it’s not really my area of enthusiasm and so I don’t feel quite so excited — though in 80 years from now people will doubtless be looking back going “Oh my days, how did someone not get excited about X and Y in the same issue together!” so I guess it’s all relative…

Thanks for the Woolrich/Irish recommendations; am keen to check out more by him on my recent experiences, so all recommendations are being noted down.

LikeLike

Pingback: My Book Notes: “Mystery in Room 913” (1938) a short story by Cornell Woolrich – A Crime is Afoot

Pingback: “Mystery In Room 913”: I wish you would step back from that ledge, my friend. | Lucynka Reviews Obscure Bullshit