Look, it took me a long time to appreciate the intelligence of the inverted mystery, in which we know who committed the crime and have to watch both them struggle over it and their eventual discoverer working out the threads of the case. Bugt the important thing is that I got there in the end.

Plenty of examples exist in modern(ish) media, with Columbo being, I believe, almost entirely inverted mysteries — the killer was always the famous guest star, and we watched them set up and execute the crime time after time — and even one episode of Jonathan Creek going weirdly inverted after being a whodunnit for years before (and after). Having now overed a moderate range of its possibilities, I will pick my current ten favourites today.

So. They are, by original release:

1. Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight (1930) by R. Austin Freeman

In which the eponymous Pottermack murders a blackmailer and then goes to repeated and incredible lengths to give, well, various impressions about the dead man. My first experience of the novels of R. Austin Freeman, this cemented something in my mind that would go on to become a firm conviction of the man’s genius, as he keeps his scientific principles pure, his characters achingly human, his ideas magnificently practical — he would, so the accepted wisdom goes, try out his criminals’ schemes himself to ensure a) they’d work and b) he was describing the processes accurately — and his plot boiling brilliantly. One of the Golden Age’s masterpieces, pure and simple. [My review]

2. The Norwich Victims (1932) by Francis Beeding

The Norwich Victims (1932) is one of those books that makes you understand why someone would be drawn to the inverted mystery in the first place. Murder for cash is the crime here, with a young policeman put on the case of a teacher seemingly slain for no reason…and a string of people who no longer exist being the last who had anything to do with her. This falls down very slightly on the detection, in that the terminal development was not within our sleuth’s understanding to make, but it enables an idea so superbly striking that I’m willing to forgive it. If you thought that knowing the killer would rob such an undertaking of any intrigue or intelligent surprises, I urge to you read this to see how wrong you were. [My review]

3. Family Matters (1933) by Anthony Rolls

Most comedies about murder tends to be arch in their schemes or protagonists a la Anthony Berkeley, or to be comedic in the characters while playing the scheme with a straight face, like Leo Bruce. Family Matters (1933) by Anthony Rolls, another superb selection by the British Library for their Crime Classics range, somehow makes everything funny without cracking a single joke. The multiple perspectives from which this is told allows characters to be presented in their own earnest outlook and then skewered by the opinions of someone else, and how everyone carries on while the awareness of them roils around you like thunder is a phenomenal experience. Simply divine. [My review]

4. Mystery on Southampton Water (1934) by Freeman Wills Crofts

Not among the most well-known of Crofts’s inverted mysteries, the corporate malfeasance at the heart of Mystery on Southampton Water (1934) is all the more thrilling for the intermingling perspectives through which it is told. The criminals’ scheme is, as Crofts often manages, almost heartbreakingly relatable, and their chutzpah never in doubt in some staggering sequences in which they row out across the mist-shrouded Solent. Yet their nemesis is upon them, with Inspector Joseph French bringing the full force of his ingenuity to bear on untangling the problem he’s faced with…and his enemies’ counter-moves making things both more obscure and yet, by nature of repetition, clarifying things as a horrible consequence. [My review]

5. This Way Out (1939) by James Ronald

Until a few years ago, I would have been nearly alone in my appreciation of this superb, sobering, moving tale of a man trapped in a loveless marriage. Thankfully Moonstone Press came along, and all James Ronald’s criminous stories are now readily available to everyone for sensible money. This is written without any sense of fanfare, which might explain how it seems to have gone largely unnoticed for decades, but as an examination of the human side of murder, both the inspiration and the dreadful knowledge that lingers afterwards, this is very probably the best example ever put on the page. Yes, you’re appalled, because what about Title X? Well, all I need to tell you about Title X is that This Way Out is better. [My review]

6. The Bride Wore Black (1940) by Cornell Woolrich

You don’t see Cornell Woolrich’s criminous debut discussed much when the best inverted mysteries are mentioned, and I’m not sure why. Maybe people think of it more as Suspense, but it undoubtedly qualifies: our eponymous lady committing a series of murders, and the police following in her wake trying to make sense of how she’s achieved her goal, why she’s doing it, and who she is. Contains some of the very best edge-of-your-seat sequences in the genre — hell, of any genre — and wraps up with an ending that is impossible to forget. Woolrich would explore these ideas again, but hit it off so damn perfectly at first swing that it’s difficult not to feel that he could have never written another word and we’d still be lauding him to this day. [My review]

7. The Case of the Crimson Kiss [n] (1948) by Erle Stanley Gardner

Two names not typically associated with the inverted mystery are Erle Stanley Gardner and Perry Mason. Yet the two did collaborate in the subgenre once, and this very entertaining novella is the outcome. To tell you that it’s breathlessly fast-moving is hardly news, but the way the murder is resolved — a second murder, incidentally, is told in a more traditional whodunnit manner, to perhaps assuage the confused ire of those who didn’t come to this place for this sort of thing — is very, very clever. Plus, Gardner really knows these characters by now, so the whole thing positively ripples with beautiful grace notes that speak of their various, deep connections. So good, you’ll wish he wrote a dozen of ’em.[My review]

8. The Chocolate Cobweb (1948) by Charlotte Armstrong

Authors choose to write inverted mysteries for, I’m sure, a number of reasons: because they have a clever clue to slide in front of the reader, or because they wish to toy with the notion of a genuinely sympathetic criminal and so to give more air time to their motivations. Charlotte Armstrong’s The Chocolate Cobweb (1948) is a masterpiece of delving into the mind of someone who has such a monomania that it has driven them to the point of madness, and seeing it unfold — seriously, now, don’t even know who it is before reading the book, it’s such a brilliant shock early on — is the very acme of what this genre was able to offer. Heart-pounding stuff, all the way through, and made all the more powerful by the canny insanity of our murderous miscreant. [My review]

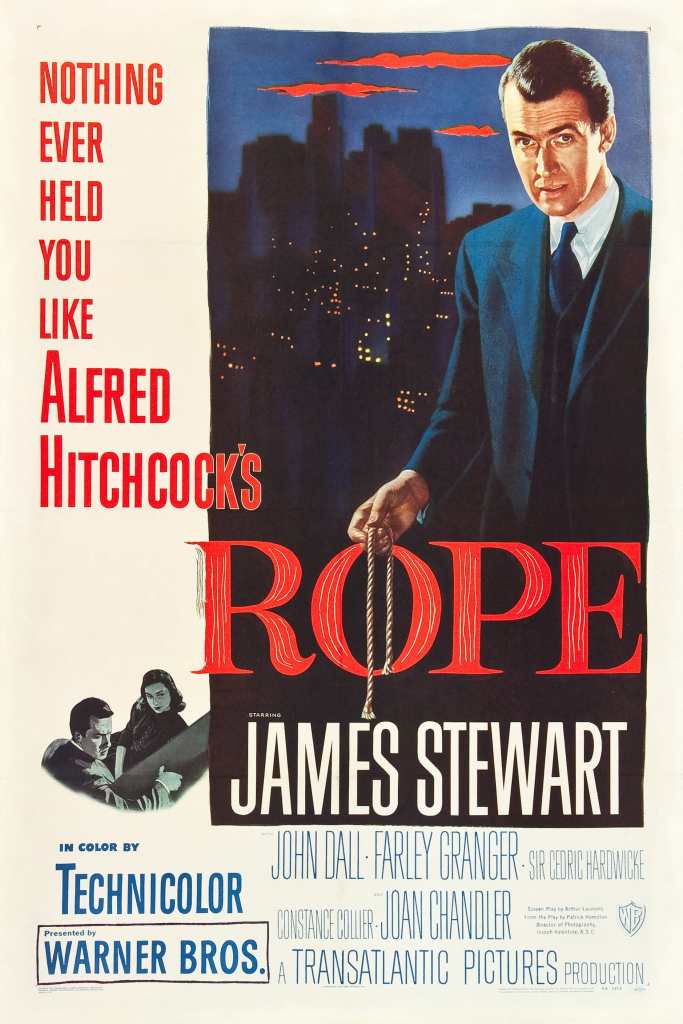

9. Rope (1948) by Arthur Laurents

I never said they’d all be books, did I? And, yes, while I’ll admit that I’m being slightly swayed by the presentation of this — those long takes really do amp up the excitement, giving the impression of really being there and watching it unfold in real time — I retain such hugely fond memories of this that I’m prepared to say it was the work which made inverted mysteries finally make sense to me. Two students kill a man, hide him in their rooms, and then invite a group of people in for a party — as horrendous a setup as you could ask for, and yet the slow unpicking of the murder by James Stewart’s character is calculating, compelling, and, ultimately, full of devastation (his face when he finds the body…perfection). Other Hitchcock inverteds might compel themselves to you; if so, write your own list.

10. A Kiss Before Dying (1953) by Ira Levin

There are authors who put their toe into criminous fiction and then, for reasons of their own, moved on to the regret of every sane person who has ever read them. Think John Sladek or someone who wasn’t A.A. Milne. To that list, add Ira Levin, whose A Kiss Before Dying (1953) shows once again how the concept of knowing your killer — though, arguably, we also don’t know the killer, which is kind of genius in its own way — can be mined until you feel like someone has squeezed the breath out of you. That might not sound like fun to you, but if you think you’re a fan of suspense writing and you somehow haven’t read this then, my goodness, do you have a treat in store. A simply sublime piece of tension-riddle play, with some great reversals and a few moments to take the breath away. [My review]

Some honorary mentions…

I suppose the inverted mystery has become a little like the locked room mystery, in that the terms is often misapplied — a true inverted mystery should have elements of detection about it, whereas something where we simply follow the criminal is…what? Merely a crime novel? That’s in part why Malice Aforethought (1931) by Francis Iles doesn’t make this list (also — prepare yourself — I’m not actually convinced it’s the masterpiece many claim). The same applies for Heir Presumptive (1935) by Henry Wade, which is one of the true, copper-bottomed masterpieces put out during the Golden Age. See also the doom-soaked Double Indemnity (1936) by James M. Cain, which was a shoo-in for this list until I reread it and realised that the investigation into the murder by our downfall-crossed lovers all happens in the background. And then there’s Pop. 1280 (1964) by Jim Thompson, a masterpiece in its own way but perhaps too late to qualify as from the Golden Age. Not, I suppose, that I said that up front. Hm.

~

My Ten Favourite…

An exceptional collection of books with a couple I have yet to read (so looking forward to addressing that!). I will always champion A Kiss Before Dying but there are some other excellent choices here too!

LikeLike

I’ve banged on for a while now about how “Malice Aforethought” is NOT an inverted mystery, because… well, it has no mystery in it. It’s also barely a crime novel, since the actual crime portions take up about 10-15% of the book? Also, I do agree with you that all the books on your list are better, even though I still do love MA. It’s brilliantly written and so incredibly funny throughout even though Iles/Berkeley never makes light of murder or any of his anti-hero’s extracurricular activities. That tonal balance between odium and humorous glee is what impressed me the most about the book. I was less impressed by the pacing (something I feel is this author’s perennial Achilles’ Heel), and the ending is a bit of a damp squib. The blatant misogyny on display is also quite unappealing, especially since Berkeley’s own professed views sometimes seem disturbingly close to Bickleigh’s. I think some of Ilesian proteges eventually surpassed their master, most notably Crofts’ dabbles in the subgenre (“The 12.30 from Croydon” is essentially a more mystery-oriented redress of “Malice Aforethought”), and Patricia Highsmith’s “Deep Water” which really blurs the line between odium and sympathy for the Devil as only she can.

As for your top 10 choices, I have no quibbles at all. OK, maybe I do prefer “The 12.30 from Croydon,” and I’m not sure “The Bride Wore Black” REALLY qualifies, but it’s as good a choice as any it’s possible to make. It’s a little strange you credit “Rope” solely to Laurents when it so faithfully adapts Patrick Hamilton’s play. I think the best parts of that script stem from the original. Speaking of Hamilton, by the way, “Mr Stimpson & Mr Gorse” could also qualify as an inverted mystery, and a very witty one at that.

Personally, I respond the most to more experimental inverted mysteries, one which play around with the formula a bit. “A Kiss Before Dying” is a superb example. “Columbo,” which is indeed made up entirely of inverted mysteries except for a single whodunit (which is also the most roundly despised episode the show), had a few clever inversions of the inverted mystery itself such as the episode in which we know one of a pair of twins is the killer, but we don’t know which one!

That’s why “Furuhata Ninzaburo” is my choice for my personal favourite inverted mystery in any medium. Every episode of that show feels like a novel approach to the subgenre. Whether it’s an inverted mystery in which we follow a man trying to commit suicide, or an inverted mystery in which one twin takes place of another, or an inverted mystery in which the killer is a real celebrity playing himself… That Koki Mitani sure knew how to write them. I especially love the episode in which Furuhata Ninzaburo finds himself investigating a traditional Seishi Yokomizo mystery in a remote Japanese village, and the guest star is the actor best known for playing Kosuke Kindaichi in the film series. There’s meta on top of meta in that one. (That’s also incidentally the episode in which the killer commits a murder based on a locked room story he wrote when he was a child. Clever bastard!)

LikeLike