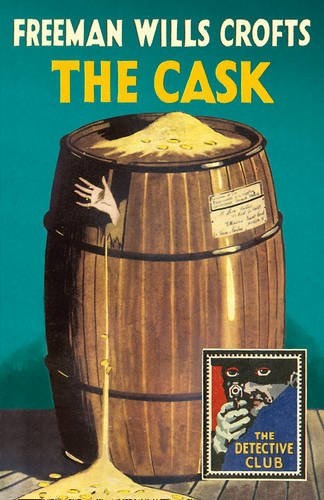

If I asked you to name the debut novel of a hugely influential detective fiction author that was originally written in 1916, published four years later, featured a character called Hastings, and had its ending rewritten at the publisher’s request to remove a courtroom/trial sequence…you’d no doubt be surprised just how much The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) by Agatha Christie and The Cask (1920) by Freeman Wills Crofts had in common. The intervening century has been kinder to Christie than to Crofts in both literary reputation and availability, and their divergence from these surface-level similarities is no doubt a part of that.

On paper, The Cask is the exact kind of puzzle that the prevailing literary trend at the time would have served up: a ship is unloaded at dock, an especially heavy cask overbalances things and falls to the ground, splitting open. Out fall gold sovereigns…and upon inspection a human hand is viewed within. Crofts’ frank genius — yes, genius — was to take the narrative here by the scruff of the neck and, instead of letting it meander down a well-trodden path of International Gangs, Kidnappings, and Peril, to turn it into a microscopic investigation of near-fractal detail and event. Everything you can look into is looked into, and from each event spins more and more possibilities and occurrences. As a narrative is does occasionally falter, but more often than not these stumbling efforts at detail and rigour are then paid off tenfold: chapter 6, ‘The Art of Detection’, is after ten decades now a little hoary and tedious, but its effect on the relevant person when their precise actions are repeated to them is salutary for what the genre was to become.

That microscopic detail has dogged Crofts ever since, and not unfairly, but this is also much more than simply combinatorics as applied to detection. The first section, in which Inspector Burnley is summoned to the docks to investigate, has about it the incident and invention of a pre-forensics 24: men and casks appear and disappear, motives and implications shift and are reframed, and the steady unravelling of what appears and what actually is could not be better marshalled. It’s whirligig stuff, all the more brilliant for how thoroughly each development is worked into the narrative — at each stage of circumspection, someone finds a way to mislead and achieve their aim. That Crofts’ criminals are assiduous in their schemes is old hat now, but at the time, when a genius amateur could point a finger with virtually nothing in the way of reasoning, seeing someone making their bread by so careful a plan laid out so openly would have been a revelation. No wonder it sold by the barrow-load.

Crofts would never top anyone’s list of the genre’s most nuanced stylists, but little flashes of fabulous writing are always there to be found, with wry gems like:

Palmer’s statement, divested of its Cockney slang and picturesque embellishments, was as follows.

Equally, the grief of one character is given more than adequate voice with a simple pathos that never seeks to outstay its welcome:

The sun shone gaily in with never a hint of tragedy, lighting up the bent figure in the armchair and bringing into pitiless prominence the details that should have been cloaked decently in shadow, from the drops of moisture on the drawn brown to the hands clenched white beneath the edge of the desk.

And if you can find a more steel-edged moment in fiction from this — or possibly any — era than the line “Keep them” from the denouement, well, good luck to you. Sure, we don’t get to indulge in the same breathless love of the outdoors that enriches the likes of The Groote Park Murder (1923), but when things do eventually move to France you at least get the feeling that Crofts has been there to see it himself, and tiny details speckle the further investigations of Burnley and the Sûreté’s Lefarge.

Tonally, you can feel the genre beginning to take shape with the way these two are able to apply some brilliant logic at times and yet jump to (or avoid) startlingly obvious conclusions at others: sawdust on a carpet, interior monologues about motive, automatic assumptions about shipping routes…jeepers, these two never miss a chance to leap over the obvious. And yet those deductions from chapter 6, or the suspicions about the provenance of a letter, or the refusal to accept that there is a body in the cask when it was clearly marked ‘Statuary’ and their witnesses only saw a hand…when this sort of detail was unexplored, there will inevitably be some unevenness. It’s also hilarious how freely they’re able to just pay people for information and then trust that what they’ve received is the real deal. The yen to believe is strong in these two.

The tenacious nature of Burnley and Lefarge is something that would betoken every Crofts protagonist, and two distinct lines in this narrative typify Crofts minutely: “Many and many a thorny problem had been solved with far less to go on” and “The oversights of criminals were notorious”. Yet they would — to employ the argot of the era — have pulled a massive boner but for private investigator Georges La Touche sweeping in to save their reputations come the final section (no spoiler; the fact that B&L have a watertight case with 100 pages to go will be a gigantic clue after all these years…), where come the final summation it’s fascinating to see the pattern finally drop into place — the essential idea is staggeringly simple once you get down to it, and dressed up beautifully — along with deliberate errors made by our criminal that were, as far as we know, entirely overlooked (a wonderful touch, that; a piece of utter beauty). Yes, some luck is involved — thank heavens that typist is so attractive, or that Constable Walker had read his “masters of detective fiction” — but the brains behind calling those footprints, say, are undeniable and account for the vast majority of the progress made.

In summation, it’s possible even after a hundred years to see how the confidence of detail here would cause a revolution in detective fiction. The measured, deliberate action of our protagonists, the intelligence of (most of) their deductions, the infernal brilliance of the villain in concocting what is, after all, a very practicable and believable ruse to cover their tracks, and the hugely satisfying ways the complexity builds without ever seeking to confound simply by weight of incident (Look at this! And this! And this! And these!) deserves so much credit for how it changed what had been until then a far messier, looser set of expectations. That Crofts and Christie, starting their careers as close together as they did, completely altered the face of detective fiction is surely undeniable. And that there’s still so much to enjoy in the texts that contributed so much to this volte face is a testament to the enduring alternatives they offered. Not always an easy read, not always a thrilling one, but a brilliant, brilliant, brilliant game-changing novel that still has the power to surprise even after all this time.

In summation, it’s possible even after a hundred years to see how the confidence of detail here would cause a revolution in detective fiction. The measured, deliberate action of our protagonists, the intelligence of (most of) their deductions, the infernal brilliance of the villain in concocting what is, after all, a very practicable and believable ruse to cover their tracks, and the hugely satisfying ways the complexity builds without ever seeking to confound simply by weight of incident (Look at this! And this! And this! And these!) deserves so much credit for how it changed what had been until then a far messier, looser set of expectations. That Crofts and Christie, starting their careers as close together as they did, completely altered the face of detective fiction is surely undeniable. And that there’s still so much to enjoy in the texts that contributed so much to this volte face is a testament to the enduring alternatives they offered. Not always an easy read, not always a thrilling one, but a brilliant, brilliant, brilliant game-changing novel that still has the power to surprise even after all this time.

~

See also

Martin Edwards: One of the suspects has an apparently unbreakable alibi, and much of the story is devoted to attempts to crack it. This was to become a trade mark device for Crofts. I was impressed by the way he maintained my interest in the story from start to finish. Yes, by modern standards, it is slow, but the elaborations of the puzzle are very well done. Much of the book is set in France, and the fact that many Golden Age novels had a rather cosmopolitan feel is rather under-estimated by their detractors. All in all, this is a book that is still definitely worth reading today.

Nick @ The Grandest Game in the World: It’s an enormous work (400 pages), but never boring—I was reminded of Heine’s famous comparison of Meyerbeer’s Huguenots to a Gothic cathedral, built by ‘a giant in the conception and design of the whole, a dwarf in the exhaustive execution of detail’. A rich and solid plot, with many leads to follow (the various investigators continually find new information) and the reader knowing as much as (and deducing less than) the police, make it a fascinating work.

TomCat @ Beneath the Stains of Time: The Cask is, at it’s core, a fairly simple case and the murderer successfully muddled the waters, which is probably when Crofts realized he had plotted himself in a corner and this resulted in a rushed, somewhat forced ending … I think the book would’ve had genuine status as a classic today if the murderer had laughed in La Touche’s face and wished him luck with proving his case in court, especially as an ending to an old-fashioned, almost charming story, but would such darkness have gone over well at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties?

~

Freeman Wills Crofts on The Invisible Event:

The Standalones

The Cask (1920)

The Ponson Case (1921)

The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922)

The Groote Park Murder (1923)

Featuring Inspector Joseph French

Inspector French’s Greatest Case (1924)

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery (1926)

Inspector French and the Starvel Hollow Tragedy (1927)

The Sea Mystery (1928)

The Box Office Murders, a.k.a. The Purple Sickle Murders (1929)

Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930)

Mystery in the Channel, a.k.a. Mystery in the English Channel (1931)

Sudden Death (1932)

Death on the Way, a.k.a. Double Death (1932)

The Hog’s Back Mystery, a.k.a. The Strange Case of Dr. Earle (1933)

The 12.30 from Croydon, a.k.a. Wilful and Premeditated (1934)

The Mystery on Southampton Water, a.k.a. Crime on the Solent (1934)

Crime at Guildford, a.k.a. The Crime at Nornes (1935)

The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’ (1936)

Man Overboard!, a.k.a. Cold-Blooded Murder (1936)

Found Floating (1937)

The End of Andrew Harrison, a.k.a. The Futile Alibi (1938)

Antidote to Venom (1938)

Fatal Venture, a.k.a. Tragedy in the Hollow (1939)

Golden Ashes (1940)

James Tarrant, Adventurer, a.k.a. Circumstantial Evidence (1941)

A Losing Game, a.k.a. The Losing Game (1941)

Fear Comes to Chalfont (1942)

The Affair at Little Wokeham, a.k.a. Double Tragedy (1943)

Young Robin Brand, Detective (1947)

The 9.50 Up Express and Other Stories [ss] (2020) ed. Tony Medawar

Some fascinating observations here that make me excited for the prospect of reading this one whenever I finally get around to tackling it. Was there anything at all in common with The Sea Mystery (for the benefit of anyone else reading this comment – a later Inspector French novel that spoils this one) in the end?

LikeLike

Oh. dammit, I knew I forgot something!

Short answer: no. Aside from a body in a wooden box of transport there’s no similarity that has any significance. Which I’m pleased about, because it feeds into my “Crofts always tried to write a different book” theory. The Sea Mystery is someone looking to expand their remit once they have a firmer grip on the sorts of books they write, where The Cask is by nature somewhat of an apprentice work trying to figure out both the author’s writing and the potentialities in this genre he’s trying for the first time.

LikeLike

Awesome. I had assuming so by the omission but it is good to know!

LikeLike

Must re-read this soon .i have a copy somewhere.

I’ve recently read ‘Golden Ashes’ which has been generally poorly received. My problem with ‘Ashes’ is that there are two bits where Crofts plot goes awry. There’s a ‘why didn’t she say x ‘ and a ‘why did he do y ‘ with no explanation other that it would harm the plot if they were answered. And that is so un-Croft’s like.

Apart from his famous attention to detail I like the authors ‘voice’. It’s a difficult thing to quantify but I always think Croft’s would have been a thoroughly decent bloke to know.

LikeLike

It’s interesting you mention the authorly voice, because that’s something I’ve really warmed to with Crofts — I look back at the first book of his I read, The HGog’s Back Mystery, and I reckon I’d enjoy it far more now that I’m attuned to his particular style of oration.

I was a little on the fence of whether to read this now or wait and read it last since it was spoiled by The Sea Mystery. What settled it for me was that a link was posted on the Facebook GAD group to the first ten minutes of the audiobook, which has recently been released, and I loved how perfectly the narrator’s voice fitted with the prose Crofts had written. Once I heard that, I couldn’t get it out of my head and so knew I had to read it.

And, yeah, I know exactly what you mean; I can easily believe Crofts was a lovely man.

LikeLike

haha you’re never going to convince me that Crofts is for me, but it remains enjoyable to see your enjoyment of his books. I think a vicarious experience of Crofts is the one for me!

LikeLike

It’s okay, Kate, we’ll always have Tragedy at Law…

LikeLike

Glad to see you liked this. I struggled with it but that was many years ago and I’ve been enjoying Crofts more and more in recent times. I may even go back and give this a look again, but not for some time as I have plenty by both Crofts and others to be getting on with at present.

LikeLike

The length of this commends it to those who are already at least partially signed up to Crofts, I feel, or those who are willing to commit to at least a few books no matter what their first experience. I defy anyone to find nothing to enjoy in it — if that’s the case, I doubt that person is reading the correct genre — but I’ll also fully allow that there are aspects of this that could prove challenging. It’s a fascinating document, though, and my interest in the unfolding of GAD’s wings would have gotten me through on its own even if I hadn’t also been caught up in the story. But yeah, this, Crofts, and any author you care to name, won’t be for everyone.

LikeLike

I had assumed I wouldn’t be reading this given an overlap with The Sea Mystery, but it looks like that’s not the case. It sounds like one I’ll need to track down. I really do need to get around to reading my second Crofts novel (currently Death of a Train is five down in the miscellaneous author TBR pile).

It’s tough though man. I’m trying to read a Carr and a Christie nearly every month. Mix that in with wanting to make some occasional progress on Brand, Queen, Boucher, Quentin, Fearn, Crispin, and Halter. Then throw in sub-genre’s like honkaku (first review pending…) and “classic” reads by the likes of Rawson, Berkeley, Sladek, Smith, and Roscoe. Plus, dabbling in Roos, Gallico, Blake, McCloy, Brean… I’m sure you’re feeling an immense amount of sympathy for my plight.

LikeLike

And Byrnside — don’t forget Byrnside!

A number of years ago I set myself a similar sort of reading target: everything would be either an impossible crime, classic work of detection, or a classic work of SF. I think I lasted about 12 books before the desire to simply read something that took my fancy kicked in, and it felt like a weight coming off my shoulders. Maybe relax your expectations. You’ll get to all this stuff, there’s plenty of time.

I struggle in a similar sort of way with this blog: I need to read usually two or three books a week to fulfil my own deadlines, and that leaves me very little time to read stuff just for the hell of reading it — I’ve had all 1144 pages of Pandora’s Star by Peter F. Hamilton on my TBR for over a year now, but when am I going to get time to dive into that brobdingnagian tome? I’m lucky to get through a 250-page GAD novel in time for my Thursday reviews sometimes…

Anyway, yes, this is worth tracing down since it is different in just about every regard to The Sea Mystery. But there’s no rush, remember: you’ve got plenty of time to find the rarest paperback edition ever for about $3.20 — actually, upon reflection, that’s far more than you’d have to pay given your track record. And if you have to compromise and get the new edition at the bottom of this review, at least it has an introduction by Dolores Gordon-Smith, and she’s so delightful a person that I can’t believe that would be anything other than a wonderful take on this book.

Win/win, really, Ben 🙂

LikeLike

I had to settle for a House of Stratus copy for $3 more than that. Although speaking of House of Stratus deals, I think you have everyone beat!

LikeLike

Perhaps, but given that it’s currently going to cost about £150 to get Andrew Harrison, Fear Comes to Chalfont, and Murderers Make Mistakes to complete my Crofts library…well, that changes things somewhat!

LikeLike

The opening section of The Cask is quite brilliant in the way that Burnley keeps losing the trail of the cask, but each time by the thinnest of clues manages to pick it up again. This is taut, edge-of-the-seat detection.

But around the middle of the book it goes a bit flabby. The problem is that there is only one real suspect, so it’s clear that the rest of the book is going to be a matter of breaking his alibi, and the flaws in the alibi are not so very well concealed, so that for the reader who spots them it becomes a matter of waiting a very long time for the detectives to cotton on to problems that you have already spotted, like which day Boirac made the phone call from the café in Charenton. Possibly this aspect of the book worked better in 1920 when the readers would have been less familiar with this kind of alibi-breaking exercise. In later books Crofts got better at pacing, introducing new material continually so that the detective never lags too far behind the reader.

It doesn’t help that the detectives keep changing. It is a realistic aspect of a police investigation that, say, Burnley of Scotland Yard should handle the English side and Lefarge of the Sûreté should handle the French. But it means that the sympathy the reader might have built up for the one is lost and has to be re-established for the other. Crofts persisted in this approach for several books — The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922) and The Groote Park Murder (1923) also swap detectives midway to their detriment.

The ending is simply terrible, descending into feeble thriller territory, with death-traps and cliff-hangers and an off-stage denouement. I don’t know what made Crofts do it — maybe he felt he had written himself into a corner whereby it was not possible for the detectives to acquire enough evidence to secure a conviction, so that only a violent ending would work. More likely though is that he had a secret liking for the thriller. There are incongruent thriller-style endings in many of his books, which has the (I think unintended) effect of of undermining the competence of his detectives. Inspector French, for example, is portrayed as very sharp for 95% of each of his books, but then he always makes an elementary blunder near the end resulting in an unnecessary scene of violence instead of the criminals coming quietly.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m glad we agree about the opening section, at least. I think many people will be surprised at how intelligently put together that first section is; certainly the density of switchbacks and revelations took me completely unawares, and I count myself as a fan of Crofts.

I think your observation that the middle section “worked better in 1920 when the readers would have been less familiar with this kind of alibi-breaking exercise” is the key thing here. It’s worth remembering that detective fiction like this wasn’t a think when Crofts wrote The Cask — as I said above, it was generally genius amateurs jumping to rock-solid answers on the flimsiest of reasoning — and so the sheer degree of work and declaration in here betokens how much little points like that phone call would be taken for granted. It’s a narrow alibi trick at best, possibly only outdone in these early Crofts books by the one in The Groote Park Murder, but the weight given to witness testimony in other matters speaks to how trusting the general attitude was towards this sort of endeavour in crime fiction: if the guys says it happened on Monday, then it happened on Monday. Crofts would absolutely improve, we agree there, but it seems a little harsh to hold against this first swing that it is a product of its time.

Personally, I like the change of detectives in these early books. The key pone for me is The Pit Prop Syndicate with its two parts called “The Amateurs” and “The Professionals”: the difference in approach is the key thing, each of his early investigators is limited in some way — be it authority, insight, or rigour — and he then needs someone else to come in and provide that spark, that moment of inspiration, to crack the thing (La Touche here being the perfect example). Do the books suffer for a change of central character? Maybe, but it’s not as if Crofts was every huge on characterisation to begin with, and his books always strike me much more as being about the criminals than the investigators.

The endings are, I feel, a product of their time — not necessarily that Crofts was in love with that kind of story, but that such an ending was just how stories of this sort ended: Holmes bearding the criminals in their den, Lattimer Shrive waiting in the dark with a gun, Sexton Blake doing some highly unlikely shenanigans that usually involved a fight…that’s just how criminal were caught back then. That a more sedate, measured ending became part of the genre is, I’d argue on very little evidence, probably a result of the more measured approach that Crofts showed could be taken where these sorts of tales were involved. I also think some of his thriller-ish endings — The Cheyne Mystery in particular, fight me — are brilliantly apposite in their deployment. I agree that the amalgamation of genres isn’t always done smoothly, but when you’re the one laying the road you’re merely showing the way for others to follow!

LikeLike

I was harsh about The Cask in my comment above but I very much agree with you that, considered as a debut novel, it is very impressive. Crofts takes the police procedural from a minor element in works like Bleak House and The Moonstone, expands it to fill a novel, and goes to invent the “breaking the unbreakable alibi” plot for an encore. And this without any planning! Crofts says in the introduction, “The Cask was built up, as it were, from hand to mouth. Each new ‘good notion’ was incorporated as it occurred to me, with the not infrequent result that it came out again next day, being found to conflict hopelessly with something else.” Given the circumstances of composition, it’s amazing that the book turned out readable at all!

It’s often the fate of a pioneering work to contain flaws that the author later figures out how to repair. The problem in The Cask is that the two elements of the puzzle are solved sequentially: first the movements of cask are established (which retains suspense), eventually revealing the suspect, and then his alibi has to be broken (which falls flat). In later novels, Crofts would figure out how to entwine the two aspects of the mystery, so that the detective’s progress on the mechanism of the crime proceeds in parallel with the breakdown of the alibi, maintaining the suspense on both points, and allowing one part of the investigation to inform the other (consider for example Sir John Magill’s Last Journey).

As for thriller-style endings, the one in The Cheyne Mystery is more excusable than most, since that book has thriller elements throughout. But in The Cask and elsewhere I think it shows that Crofts wasn’t confident in the original elements of his own work. He says in the introduction, “Were I writing The Cask to-day, it would probably turn out a very different book. All the stuff about the journeyings of the cask through London is irrelevant padding, and really ought to come out.” But this part of the novel is the best bit! Crofts’ great contribution to the genre was the dogged and meticulous investigations of his humdrum policemen, and not his sub-Edgar-Wallace fisticuffs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the quotes from Crofts’ introduction — I should try and track that down, since my House of Stratus edition doesn’t have it…seems a weird omission, but I guess such things weren’t foremost in the minds of GAD reissuers at the time. Love the idea of him writing it on the hoof; good heavens, what an accomplishment!

Magill is not the best Crofts, but I agree with you that it does demonstrate his genius in juggling the aspects of the plot. I think — I could be wrong — that it was the first book he wrote as a full-time writer, having given up work at the end of the 1920s, so maybe the fact that he didn’t have to concentrate on anything else away from it finally enabled him to unleash all his labyrinthine complexity. It’s a wonderful example of how to reframe existing narrative events, and should be a textbook for anyone wanting to write a legitimately twisty crime novel.

I’ll keep an eye out for these thriller-style endings, because you’ve made me curious. I’m still a Crofts neophyte — a mere ten books read — and so have plenty of remaining scope to look at that aspect of his writing. Thus far, I’ve been so swept up in enjoying what he writes that I’ve not noticed the Edgar Wallace-ish elements beyond The Cask and The Cheyne Mystery…and even then, in the latter, only because someone complained about it when I thought it was beautifully apposite. French’s Greatest Case will be the next one, so I’ll keep the ending in mind and report back…

LikeLike

The copy of The Cask at the Internet Archive has Croft’s preface.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, sublime! Many thanks.

LikeLike

Am I the only one to have noted the fundamental logical flaw? If I read correctly, the cask that contained the body and transported to Paris for identification was recognised by the packers of Dupierre as being undoubtedly the very one sent to Felix via Le Havre (the 1st travel of the cask). This identification was made by a very individual feature of the wood of the cask. Later on, we learn that actually this cask did not contain the body, but that the body was all the time in the cask sent to Boiret and that an exchange took place. But the positive identification by an individual feature of the cask is thereby rendered illogical, as most probably not both casks had this individual feature of the wood.

LikeLike

Huh, you could be onto something there — I can’t remember the precise details, but your version sounds right. How about that!? A hit, a palpable hit!

LikeLike

Pingback: My Book Notes: The Cask, 1920 by Freeman Wills Crofts – A Crime is Afoot

Pingback: Forgotten Book of 1920: The Cask by Freeman Wills Crofts – a hot cup of pleasure

I read The Cask after The Sea Mystery and even though that book spoiled this one, it’s always interesting to see how authors adjust subsequent to their first book.

The Cask seemed to me overly long and I thought it suffered a bit from having so many different detectives. I was fine with the British and French police collaborating but then the lawyer got involved doing some investigation/interrogation, and then he turned it over to the private detective, and the case was ultimately solved by someone who appears very late in the narrative. Plus each new investigator had to be briefed and then go through the same thought processess, which again seemed unnecessary. The central idea/plot would have been more effective with less padding obscuring it, and part of what I enjoy about the Inspector French books is traveling the entire course with him as he unravels the knot.

LikeLike

I think it’s important to remember that this sort of detective story wasn’t particularly well understood when Crofts wrote The Cask, and it would be through the experimentation you refer to (multiple sleuths, etc) that the genre started to find its shape. Fascinating to think that this stuff was being made up as Crofts wrote, and how much influence this novel in particular would have had over so may who went on to become fixtures in the genre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It takes 30 pages to finally inform the owner of the cask that there’s body in it. Quite ridiculous.

LikeLike