![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

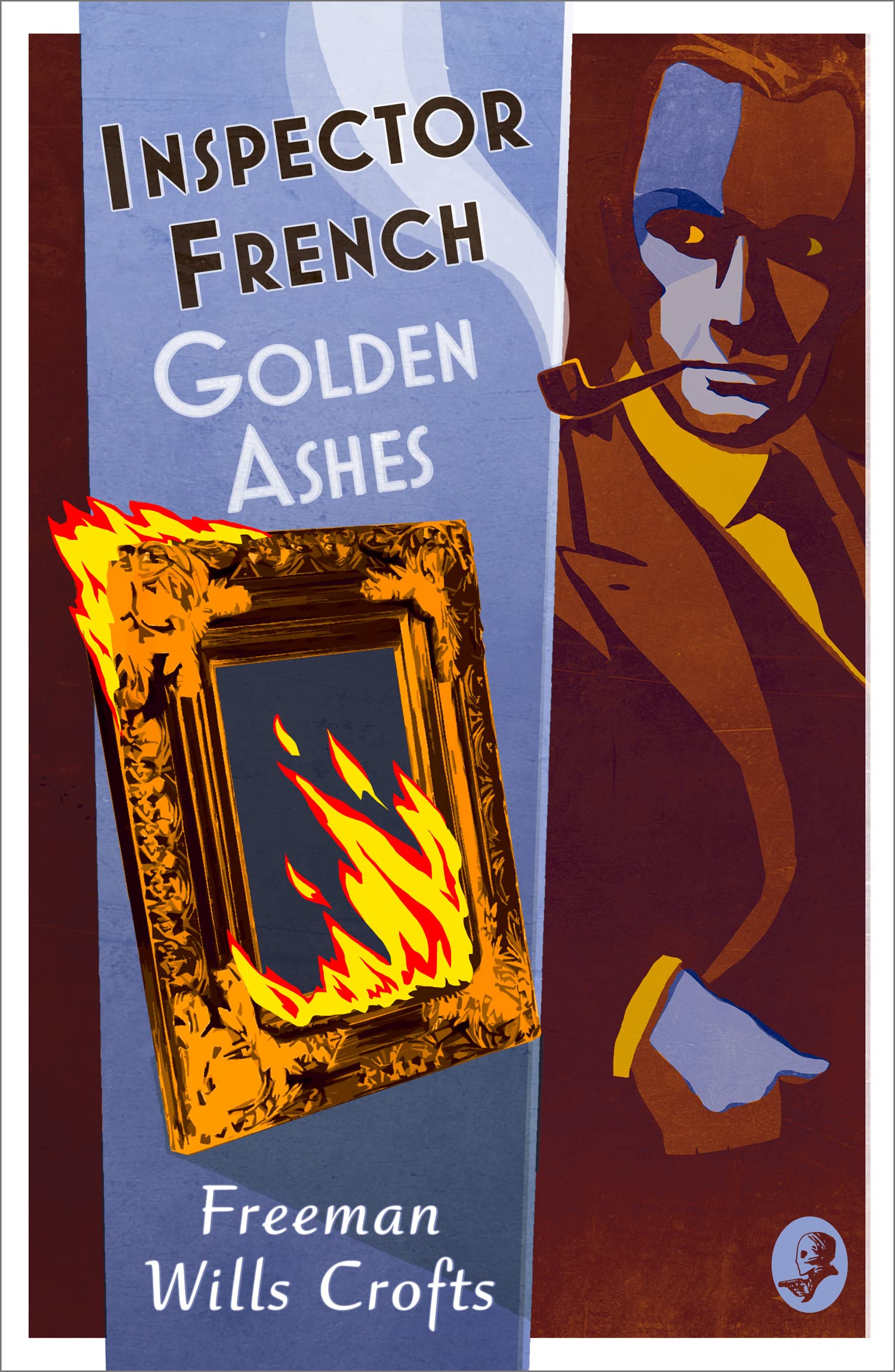

Rendered a widow and penniless at a young age — well, she is a Freeman Wills Crofts protagonist — Betty Stanton is fortunate in finding a job as housekeeper and general organiser of newly-minted baronet Sir Geoffrey Buller. Betty is delighted both with the setting of Forde Manor and the enviable collection of art on display — art that is of particular interest to her friend, the famous authority Charles Barke. Before long, however, tragedy strikes — again, this is a Freeman Wills Crofts novel — and Forde Manor burns down, resulting in the loss of both the priceless artefacts within and Betty’s position. And when Charles Barke disappears soon thereafter, a certain DCI French begins to suspect that the events might be linked.

Those seeking the most devious puzzling delights of detective fiction’s Golden Age need not apply to Golden Ashes (1940), since Crofts tells you what scheme is at work before the halfway stage, so the focus is not so much on who might be guilty and what motive they could have. Instead, as has become increasingly a source of joy for me with this author, and as no-one else seems to be able to do even half as well, the book is about French accruing sufficient evidence — all the happenstance and suspicion in the world are of no use to a professional detective — to both prove that a crime has been committed and to bring the perpetrator to book.

In so many of his cases the puzzle was to reconcile what appeared to be conflicting facts, but here it was in the absence of facts that his difficulty lay.

This is, then, another patient investigation — with, it must be said, a completely redundant side quest at one point because Betty Stanton withholds information that might have been vital in clearing up the picture sooner — with multiple trips over the Channel to Paris, giving Crofts a chance to show French’s tenacity and warmth both in working with the French police and with insurance investigator Thomas Shaw.

“I’ll take that on,” Shaw offered, “though it might be convenient later to join forces.”

“You mean,” said French, “that you’ll have a shot at it, and when you fail, you’ll shove it on to me.”

Indeed, with the resolution rarely in doubt, the focus on process here feels more deliberate, with each step obviously pointing to the culprit but there being insufficient real evidence to bring the crime home. French runs down just as many loose ends as before — see him realising “bitterly” that he’s going to have to start again from the beginning at about the two-thirds mark — but with his eye always on the end point there’s less to distract you from the need for rigour and completeness. Many authors would be cutting corners twenty-four novels into their career, but not FWC.

There’s some lovely character work in here, too, such as French smoking European cigarettes “with proper British contempt”, or Shaw’s recollection of French’s views on recidivism:

“I’ll not quickly forget what he said. ‘If that chap doesn’t get a bit of help he’ll go back to Dartmoor, and the fault won’t be his. It’ll be yours and mine and the next man’s.’ And he added what I knew myself, that most old lags want nothing more than to go straight and that they’d make specially trustworthy employees, but people won’t have them and there’s nothing for them but to go back to crime.”

As ever, Crofts remains on the side of the working man — or, in this case, woman — with Betty’s case and need for employment keenly felt, and Buller’s generosity in keeping her on despite his own financial woes parsed in no uncertain terms as a positive aspect of this hard-to-like man’s personality. As is typical when telling part of his story through a young woman’s eyes — c.f. The Box Office Murders (1929), Sudden Death (1932) — Crofts goes a little HIBK at times, but then he writes that sort of stuff so well (“How maliciously Fate must have smiled at her innocence!”) it’s difficult to begrudge him his little pleasures.

The Second World War hasn’t intruded yet, either, with Crofts setting this in 1939 — though using, it seems, 1940’s calendar by invoking Sunday 17th March at one point — and so the closest we get to any international shenanigans is a hint at a previous case of French’s in which he “capture[d] the agent of a foreign government as he was leaving the country with the plans of a new and extremely hush-hush anti-aircraft gun in the lining of his suitcase”. I’m intrigued to see how the war features in Crofts’ work going forward, and tackling him chronologically is going to add, I hope, another layer of interest going forward.

I look over my four-star Crofts reviews and see that, inside of that classification, a hierarchy can still be achieved. Golden Ashes, then, falls slightly below the standard of Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930), Mystery on Southampton Water (1934), and The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’ (1936) but rises above the likes of Found Floating (1937) and Fatal Venture (1939). Fans of Mystery in the Channel (1931), Sudden Death (1932), and Antidote to Venom (1938) will find much to enjoy here, and the casual reader will, no doubt, get much from Crofts’ rigour and commitment to a realistic mien. The plot might not make total sense — rot13 for massive spoilers: vs Ohyyre’f gung uneq hc, jul abg whfg fryy gur cvpgherf ur abj bjaf? Ur’q znxr zber zbarl gung jnl, fheryl… — but I remain in love with Crofts’ work and eagerly await Inspector French’s Twenty-First Case.

~

See also

Aidan @ Mysteries Ahoy!: [E]asily the most disappointing reading experiences I have had from this author. It is not that it is badly written – but rather that it is really dull. He was capable of much, much better than this.

Jon @ GADetection wiki: There are questions, interviews, no fewer than three trips to Paris, and the customary painstaking accumulation of evidence — but all it does in the end is to confirm what we had already guessed. What it adds up to is a remarkably clumsy plot, in which the villains behave with an odd mixture of idiocy and brilliance.

~

Freeman Wills Crofts on The Invisible Event:

The Standalones

The Cask (1920)

The Ponson Case (1921)

The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922)

The Groote Park Murder (1923)

Featuring Inspector Joseph French

Inspector French’s Greatest Case (1924)

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery (1926)

Inspector French and the Starvel Hollow Tragedy (1927)

The Sea Mystery (1928)

The Box Office Murders, a.k.a. The Purple Sickle Murders (1929)

Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930)

Mystery in the Channel, a.k.a. Mystery in the English Channel (1931)

Sudden Death (1932)

Death on the Way, a.k.a. Double Death (1932)

The Hog’s Back Mystery, a.k.a. The Strange Case of Dr. Earle (1933)

The 12.30 from Croydon, a.k.a. Wilful and Premeditated (1934)

The Mystery on Southampton Water, a.k.a. Crime on the Solent (1934)

Crime at Guildford, a.k.a. The Crime at Nornes (1935)

The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’ (1936)

Man Overboard!, a.k.a. Cold-Blooded Murder (1936)

Found Floating (1937)

The End of Andrew Harrison, a.k.a. The Futile Alibi (1938)

Antidote to Venom (1938)

Fatal Venture, a.k.a. Tragedy in the Hollow (1939)

Golden Ashes (1940)

Young Robin Brand, Detective (1947)

The 9.50 Up Express and Other Stories [ss] (2020) ed. Tony Medawar

I’ve owned this one for a while, but Aidan’s review expelled it to the “I’ll probably never bother reading it” list (along with a bunch of Innes and Blake books that I bought). Not because of his negative assessment; more so because I doubt a modern reader could skim a basic plot description without immediately sensing what the scheme is. After all, why read a mystery, if there is none? Well, I think I’ve matured a bit since then, and – with my experience with Crofts and writers like Wade – I bet I’d really enjoy this. Still, it likely remains deep in the ever growing Crofts pile.

I’m curious if the scheme would have been a bit fresher back in the early 40s. I’m reading a 20s-era Wynne novel right now, and sensing that the basics of investigating how a car crash occurred might have been novel to a reader of the time.

LikeLike

Pure surmise on my part, but I feel like Crofts’ whole thesis — after decades of reading amateur detectives clear up crimes with little more than a supposition and three suspicions — was how damn hard proper police work is. The grind for actual proof is a tough one, and always at the heart of what he writes.

So, sure, he doesn’t misdirect like Christie or surprise like Carr, but Crofts’ criminals go to prison when it comes to trial. That’s part of why I love his work so much: there’s the odd surprise here and there, but I read him for the relief of that moment when it all conclusively crashes in and you know French has his man.

Seriously, you’re told the conclusion to this before halfway through; that’s not an oversight. It might not be the sort of book most GAD readers are looking for, but if it is — or if you have space in your corpus for something a little different — then it’s delightful.

LikeLike

Isn’t the point ur pna fryy gurz naq cbpxrg gur vafhenapr zbarl?

LikeLike

Oh, yes, I see now. I’m an idiot. And clearly not nearly unscrupulous enough.

LikeLike