![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

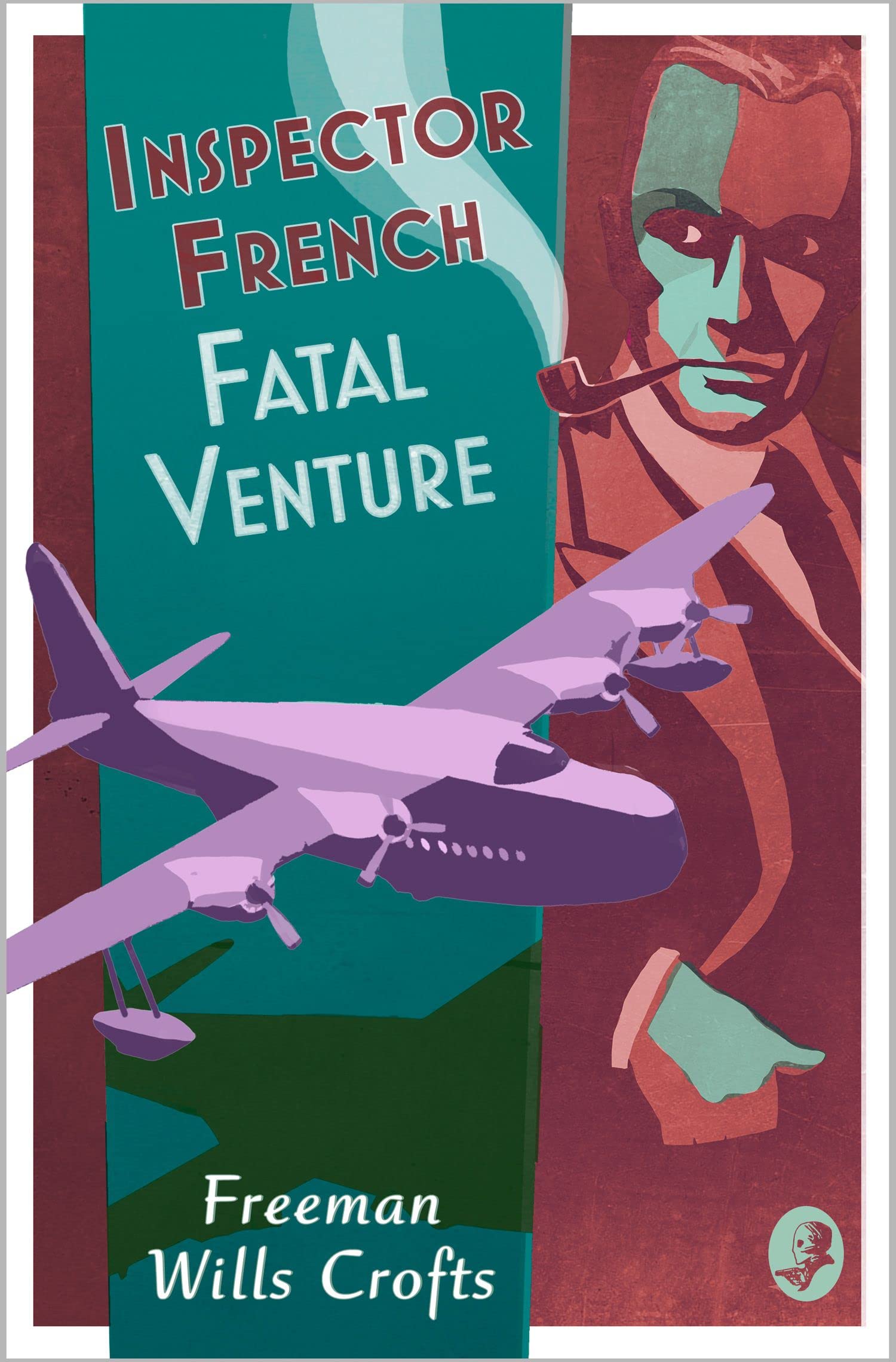

Fatal Venture (1939) represents, by my count, the ninth time in twenty-three books that Freeman Wills Crofts has devised a criminal scheme which contains a significant strain of maritime malfeasance. Compared to the mere brace involving railway timetables, you have to wonder why he’s seen as the Timbletable King rather than the Wizard of the Waterways — hell, even these excellent Harper Collins reissues make a point of highlighting his use of railway timetables, so you have to wonder if that myth will ever die. Never mind, this is still superb; highlighting why Crofts has fallen by the wayside compared to some of his peers, perhaps, but enjoyable, clever, and surprising along with it.

Rendered an orphan and penniless in his late teenage years — a common fate for a Crofts protagonist — Harry Morrison must give up his place at Cambridge and so gets a job at a travel agency. Via his own hard work and excellent professionalism — “He was as much at home with a Continental Bradshaw as the normal Englishman is with Test Match scores…” — he comes into contact with Charles Bristow who, recognising a useful man when he sees one, brings Morrison in on a business venture: refitting old cruise ships to tour the British Isles, providing a holiday that is affordable to the common man. A few hiccups along the path will see someone try to steal their idea from beneath them, and then the small matter of financial backing raise its head, but eventually all is secured and things look rosy.

Then, a sudden volte-face on the part of John Stott, their financial backer, sees the enterprise lurch in a new direction: providing not mere cruising delights for everyone, but instead a floating casino for the super-rich, who are free to gamble so long as the ship is three miles off the coast and so in international waters. The first third or so of the book is spent carefully bringing us to the point, and it is to be noted that certain of Crofts’ peers would cover the same ground in half the time, but the painstaking approach envelops you in Morrison’s difficulties, and makes the relationships ever more clearly felt, adding to the anticipation as everyone edges closer to the “shadow of the gallows”. Murder is on its way, but that anyone knows it.

Enter, and I advise you not to read the synopsis since it’s a delightful entrance, Chief Inspector Joseph French, whose involvement is brought about by the apparent existence of Freeman Wills Crofts within the French universe (“If you will ape a cheap notoriety and allow that friend of yours to write his wretched books…”), and before long the DCI and Mrs. Emily French are wrapped up in the mystery. And so begins the detective’s inexorable stalking of his prey, with clever deductions, intelligent reasoning, and no small amount of dead ends added to his burden. And this is largely what we read Crofts for, the clever way he breaks down a variety of alibis — including one piece of startlingly swift deduction which wipes away the concerted efforts by one man to remain undetected — by going over his ground methodically, intelligently, and with a minimum of agonising.

Which is not to say that there aren’t other considerations in Crofts’ writing, since he has a superb turn of phrase at times…

The sun still shone, but there was no longer brightness and warmth in its beams; just a cold, pitiless glare. The landscape was still there, but a dead landscape; hard and austere and repellent. The later accessories of his excellent lunch lay before him, but now the thought of food made him ill. The world was a great void — loathsome, damnable. For the moment he wished he was dead.

…and the style of mystery he’s writing is actually far harder to do than he makes it look. I don’t wish to give away the purpose of much of this narrative, but rest assured you’re undone by a clever piece of misdirection, and that patient, considered start makes all the more sense once you get to the end. Of the plot, let us say no more.

Some interesting turns of phrase enliven this — “Divil a one” had me scrambling for the dictionary, though a steward being “reprimanded for not mischief” turned out to be a misprint — and it’s surprising just how much character Crofts manages to give his reputedly bland detective: French takes great pleasure in seeing young lovers working out their fondness for each other, and must — via good ol’ Em — face up to the impact his profession has on those around him, giving us a different view of his job’s requirements:

In principle, he hated to find anyone guilty of murder; but when he became engrossed in a case he no longer considered personal implications — only the efficient carrying out of his work.

Also worth noting is that the guilty parties in earlier title The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’ (1936) are mentioned herein, so read that excellent book before this one to avoid spoilers. The final page of this, too, is surprisingly moving, once more tying in an earlier thread in a way that shows a far tighter hand on the tiller than might have originally been suspected, and rewarding the patient build of the first half.

The nineteenth case of French’s to be recorded, Fatal Venture shows great ingenuity in its unusual setup, and commends Crofts as a craftsman if not a showman. I, however, get plenty of showmanship elsewhere in my reading, and love being able to rely on Crofts for considered, intelligent, patient detection, as well as the complete, breathless delight he takes in any form of travel, and so this was exactly what I wanted. Colour me even more intrigued for case number twenty…

~

Freeman Wills Crofts on The Invisible Event:

The Standalones

The Cask (1920)

The Ponson Case (1921)

The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922)

The Groote Park Murder (1923)

Featuring Inspector Joseph French

Inspector French’s Greatest Case (1924)

Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery (1926)

Inspector French and the Starvel Hollow Tragedy (1927)

The Sea Mystery (1928)

The Box Office Murders, a.k.a. The Purple Sickle Murders (1929)

Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930)

Mystery in the Channel, a.k.a. Mystery in the English Channel (1931)

Sudden Death (1932)

Death on the Way, a.k.a. Double Death (1932)

The Hog’s Back Mystery, a.k.a. The Strange Case of Dr. Earle (1933)

The 12.30 from Croydon, a.k.a. Wilful and Premeditated (1934)

The Mystery on Southampton Water, a.k.a. Crime on the Solent (1934)

Crime at Guildford, a.k.a. The Crime at Nornes (1935)

The Loss of the ‘Jane Vosper’ (1936)

Man Overboard!, a.k.a. Cold-Blooded Murder (1936)

Found Floating (1937)

The End of Andrew Harrison, a.k.a. The Futile Alibi (1938)

Antidote to Venom (1938)

Fatal Venture, a.k.a. Tragedy in the Hollow (1939)

Golden Ashes (1940)

Young Robin Brand, Detective (1947)

The 9.50 Up Express and Other Stories [ss] (2020) ed. Tony Medawar

Dear God, this one is dull. It was the first Crofts novel I managed to finish, when I was 14 (after an aborted attempt to read Jane Vosper the previous year); I didn’t read another Crofts for nearly five years.

LikeLike

The first half is very deliberately paced, but it feels like Crofts learned a lot about structure from Found Floating in that regard — another story with a slow first half which comes to life in the second.

It’s not the place to start with Crofts, and as a 14 year-old I could well believe I’d give up on it and never touch him again…but as a signed-up Croftian with some sense of what I was getting, I thoroughly enjoyed this. And the core misdirection is reasonably smart, if not exactly ground-breaking.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Divil a one” is very Irish although it’s probably pretty old fashioned now. I know people of my grandparents’ vintage used it a lot and I was very familiar with the phrase as a youngster.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would all make sense, though I don’t remember if the character using it in the book is Irish themself. Lovely to learn these archaic expressions from old detective fiction, though nothing yet holds a candle to “Hairy Aaron!”.

LikeLiked by 1 person