For the second look at novels which I suspect put me on the route to my persistent craving of a classic detection fix, we go back to an author I adored during what were probably his lean years and had moved on from once he regained his youthful popularity.

That’s right, it’s…

Dead Meat (1993) by Philip Kerr

How I encountered this book

While shopping for Airframe (1996) by Michael Crichton, the guy serving us in Ottakar’s — I love you, Waterstones, but man, I miss Ottakar’s — essentially said “If you like Michael Crichton there’s this guy called Philip Kerr who’s supposed to be quite similar…”. This comparison may have sprung from the Financial Times calling Kerr “England’s answer to Michael Crichton” in their review of his sixth novel Gridiron (1995), and that quote ending up on the cover of the paperback which had been published not too long before, but, whatever, alongside Airframe I received Gridiron for Christmas in 1996 and probably read it fairly soon thereafter (my TBR was smaller then). I got Kerr’s next book, yetis-in-the-Himalayas thriller Esau (1996), in paperback later the following year, and started to check out his back catalogue, which brought me to his fifth novel, Dead Meat (1993), probably in the final quarter of 1997.

As a complete side note, I find it interesting how, with Kerr’s star having risen in recent years when he returned to the Bernie Gunther series which comprised his first three novels, the books he was publishing when I read him — A Philosophical Investigation (1992), Dead Meat (1993), Gridiron (1995), Esau (1996), A Five Year Plan (1997), The Second Angel (1998), The Shot (1999) — went unmentioned in his list of previous titles. The likes of Dark Matter (2002) and Hitler’s Peace (2005) I can sort of understand since they weren’t published in the UK (believe me, I searched high and low), but it seems odd that such a chunk of his output was ignored (at the time of writing, even his own website doesn’t acknowledge most of them). Sure, they were inconsistent in tone and focus — killer buildings, killer yetis, an ex-con on one last job, a futuristic thriller in which a blood disease is wiping out swathes of the population, the Mafia threatening to kill JFK in the run-up to his presidential bid — but not without merit: A Five Year Plan, for one, contains one of the best final chapter twists of my young reading life.

Tonally they’re not necessarily the sort of books one would always be delighted to recall at the end of a long career — there’s a strangely aggressive sexuality to aspects of his writing which intrudes in the oddest ways in this middle tranche — but maybe the sales simply weren’t good (like I say, two of them didn’t get UK publication) and once he started winning praise and awards again he simply wanted to gloss over them. Lord knows tracking down a copy of this book was difficult enough, though the titles above were all listed in the front of his final novel, the posthumously-published Metropolis (2019) so who knows — maybe someone will reprint them following his untimely death last year.

Tonally they’re not necessarily the sort of books one would always be delighted to recall at the end of a long career — there’s a strangely aggressive sexuality to aspects of his writing which intrudes in the oddest ways in this middle tranche — but maybe the sales simply weren’t good (like I say, two of them didn’t get UK publication) and once he started winning praise and awards again he simply wanted to gloss over them. Lord knows tracking down a copy of this book was difficult enough, though the titles above were all listed in the front of his final novel, the posthumously-published Metropolis (2019) so who knows — maybe someone will reprint them following his untimely death last year.

What’s it about?

It is 1993. Following the dissolution of the Soviet regime and the establishment of a fragile democracy under Boris Yeltsin, our nameless narrator, a criminal investigator from Moscow, travels to St. Petersburg — “never ever call it Leningrad, except in retrospect,” he’s told early on. “That’s all finished now” — to see how the legendary investigator Yevgeni Ivanovich Grushko and his men at the Central Board of Investigation there are dealing with the growing issue of organised crime. “It’s an intercity liaison thing. An exchange of ideas, if you like.”

Shortly after his arrival, the body of “the country’s first investigative journalist” Mikhail Milyukin is found in a car on the outskirts of the city, having been shot in the head. A second body found bound and assassinated in the boot of the car suggests possible Mafia responsibility for the murders, and Grushko, his men, and our narrator begin to investigate against a background of food shortages, economic instability, and the fractured generations reluctant to either break with their past or embrace an uncertain future. And the murders keep on coming…

Any seeds of detection?

Sort of. Well, okay, no. Not in the sense that I typically mean when I discuss Golden Age detection and its merits. Grushko and his men slowly, laboriously follow up all possible leads — Milyukin had upset some powerful people with his journalism, and received swathes of hate mail as a result — but aside from an elderly couple accusing him of stealing food from their fridge, hardly an uncommon occurrence in this new Commonwealth of Indpendent States, there’s very little that contributes to the long game of fair play construction.

To a certain extent, this is a procedural in the manner of most modern novels of policing than anything from the Golden Age. Even the long, tedious hours of investigation that are rendered so fascinating to me in the prose of Freeman Wills Crofts feel a very different beast — Grushko, our narrator, and a couple of lieutenants simply go from scene to scene observing what’s happening, and at some point enough data has been gathered that a conclusion tying some of the actions together is reached. I picked this one mainly because I remembered a whipcrack twist in the final 20 pages, but even that wasn’t as bracing as I recalled. So, on those grounds, this was something of a failure.

Can you go home?

Yes. The absence of links to GAD aside, I loved rereading this. That comes in part from it being so very different to my usual fare, but also from how wonderfully Kerr soaks the entire tale in a sort of resigned, defeated, cynical, wry Russian fatalism that nevertheless wants to believe there is a purpose behind doing something in the face of evil. The easy, arguably lazy thing would be to compare it to Chandler for how jaded our nameless narrator comes across, the studied cynicism that permeates every level of his life, but Kerr has achieved far more than mere vodka-soaked mimesis, giving a droll twist to things that speaks of an author going native in quite spectacular fashion:

Yes. The absence of links to GAD aside, I loved rereading this. That comes in part from it being so very different to my usual fare, but also from how wonderfully Kerr soaks the entire tale in a sort of resigned, defeated, cynical, wry Russian fatalism that nevertheless wants to believe there is a purpose behind doing something in the face of evil. The easy, arguably lazy thing would be to compare it to Chandler for how jaded our nameless narrator comes across, the studied cynicism that permeates every level of his life, but Kerr has achieved far more than mere vodka-soaked mimesis, giving a droll twist to things that speaks of an author going native in quite spectacular fashion:

UFOs were a common enough interest among people; UFOs, faith-healers, spiritualism, Nostradamus, pyramid power and Satanism. When it was a matter of believing in the impossible we are a most credulous people. Maybe that’s not such a surprise. After all, we have had more than seventy years of practice.

Equally, neither Chandler nor any of his ilk ever wrote anything with the casual, hilarious savagery of…

He had spent the morning attending the execution of Gerassim ‘the Butcher’, a notorious Mafioso who had killed four members of a rival gang with a meat cleaver and then fed their dismembered limbs to his pet dogs. It’s always a problem, feeding pets in Russia.

It would be easy to dwell on the more comfortable, familiar notes like a prostitute being described as “the sort who could have smelled hard currency inside a bottle of aniseed” or the James M. Cain-ish “the fingernails on Kornilov’s right hand were so badly stained with nicotine they looked as if they were made of wood”, but Kerr’s brilliance here is to write from a Russian perspective without so much as a false note. He takes the familiar trappings of a tried and tested genre and from it draws a portrait of a people and a country so breath-takingly panoramic that it commends itself to the reading list of any study of post-Soviet Russia.

“The pavements were crammed with people who seemed rather scruffier than their Moscow counterparts,” the narrator notes early on, “but because that was only because the buildings were more beautiful”. From here you get a treatise in the flourishing of the black market under Brezhnev and how Mikhail Gorbachev’s government were, in their eagerness to embrace the fee market, responsible for the rise of organised crime that in turn became a loose collective of tribes and gangs whose confused ideologies split along lines of nationality are the only thing preventing a greater organisation of a central Mafia. This, coupled with the weakening of the rouble and the consequent yearning for the “hard currency” of US dollars or German deutschmarks then manifests itself in the full gamut of ways: from corrupt policemen taking back-handers and allow organised crime to expand its reach, to young boys shutting off the electricity of a building to trap visitors in the lifts and demand money from them to be set free. “Nobody ever hunts you down just to shake you by the hand and clap you on the back. Not in Russia” Grushko is told at one point — and you’re left in no doubt that, even if they did, you would be asked for some petrol money so they’d be able to make the trip back afterwards.

Kerr writes all of this with a startling clarity and succinctness — capturing the generational divide in this strange new world in the attitude of Grushko’s daughter and her desire to live in America with her boyfriend, whose own easy access to money is viewed with intense suspicion by Grushko and outright relief by his wife. We get a sweeping glance at the aggressive tactics employed by the television and newspapers of the new era, at the perversity of the Russian prison system, the consequences of penal servitude, and the cheapness of human life in a society where what you have is far less important than what you do with it: “with the Mafia it’s almost as important that you hit someone as it is that you hit the right person. Otherwise it looks bad for business. Like you’re letting things slide”. And this attitude extends beyond actions to the little gains evinced in daily lives — the story is told in a succession of tiny flats, of wardrobes converted into offices, of taking cheese from St. Petersburg to Moscow where there is none, and bringing chocolate from Moscow back to St. Petersburg. It’s possibly the only book you’ll ever read where the possession of a box of English soaps plays into a key part of the plot.

Kerr writes all of this with a startling clarity and succinctness — capturing the generational divide in this strange new world in the attitude of Grushko’s daughter and her desire to live in America with her boyfriend, whose own easy access to money is viewed with intense suspicion by Grushko and outright relief by his wife. We get a sweeping glance at the aggressive tactics employed by the television and newspapers of the new era, at the perversity of the Russian prison system, the consequences of penal servitude, and the cheapness of human life in a society where what you have is far less important than what you do with it: “with the Mafia it’s almost as important that you hit someone as it is that you hit the right person. Otherwise it looks bad for business. Like you’re letting things slide”. And this attitude extends beyond actions to the little gains evinced in daily lives — the story is told in a succession of tiny flats, of wardrobes converted into offices, of taking cheese from St. Petersburg to Moscow where there is none, and bringing chocolate from Moscow back to St. Petersburg. It’s possibly the only book you’ll ever read where the possession of a box of English soaps plays into a key part of the plot.

If there’s a downfall to this staggering breadth, it’s that panoramas are never good at giving a portrait of individuals. Our narrator — man, it bugs me that he doesn’t have a name — isn’t really anyone, an almost deliberate cipher except for the minor, slightly discomfiting plotline wherein he becomes rather keen on Nina Milyukin, the widow of the murdered journalist: initially finding a picture of her naked among her husband’s things, hoping to get a second look at it when revisiting her flat to ask more questions, and culminating in him asking her out on a date when her husband is barely cold in the ground (the precise timescale of events is apparently much longer than it seems — he’s apparently in St. Petersburg for a couple of months, but I’d suggest the novel takes place in under a week). This ends up in he and Grushko at loggerheads over the treatment of Nina in a key regard, but that aspect of the saga ever really landed in the way it was perhaps intended to — she’s as much of a mystery as most of the other characters we meet, and the revelation that caps off her story fits in the larger framework but also seems so obvious given how well we understand this world that it doesn’t really bruise as the sucker-punch it’s probably meant to be.

Grushko himself is caught in little moments — spotting that a young boy who witnessed a crime is an escapee from an orphanage on account of his haircut, noting that the presence of oil in a Molotov cocktail thrown through a restaurant window indicates that the perpetrators were probably professionals since it “makes the flame stick” , shaving with “an ancient electric razor [that] looked like it had been designed to shear sheep” — but despite spending time in his home he, too, remains at arm’s length. “He’s like one of those people who used to work for the NKVD. Ruthless, single-minded and utterly dedicated to what they do,” Nina says of him at one point. “No room for shades of meaning. Just black and white. Right and wrong” and, well, this could be argued either way — there’s nothing in what we see of him to either confirm or deny that conclusion, and if it’s put in there for contrast, for the reader to judge their opinion of this character against such a typing, there’s frustratingly little the reader can do with it. He’s very paternal with his men, and some of the best exchanges come from their time together:

Grushko shot a look of puzzlement at [the photographer] and then leaned towards Sasha.

“Who’s he?” he said. “Where’s Arkady, our usual man?”

“Sick,” said Sasha. “This is Dimitri.”

Grushko nodded uncertainly, and watched Dimitri turning the focus on a huge telephoto lens.

“You needn’t worry about him, sir,” said Sasha. “He used to do surveillance work for the KGB, until he got made redundant.”

“Oh? And what does he do now?”

“Weddings mostly.”

…but you never know him. Still, he at least fares better than the character who is killed in the climax, since I couldn’t even tell you now which one he was or why we should care. For a book with so much death in it, the one we’re supposed to feel is treated just as incidentally as the rest.

It’s perhaps this lack of focus on people that makes the plot feel so distant, and the sudden change in direction that I remembered from my youth wasn’t quite as shocking, obviously in part because I knew it was coming, but also because you can put the pieces together long before Grushko’s rouble finally drops. And yet it’s not really a clewed mystery, as many aspects of what occurs don’t tie into the plot at all: the adversary is never more specific than “the Mafia”, as if that itself is a sentient beast to be tamed, and each crime is committed by “the Mafia” with very little focus on acts by individuals until it turns out someone was seen at a crime scene and so becomes the focus of the next few chapters. Nevertheless, I remember vividly the impression this had on me as someone venturing into a genre, and it has stood out i my mind all these years as an example of how what starts of as a ‘simple murder’ can fit into a far more complex and surprising scheme come the end — a salutary lesson in the delights that awaited in GAD.

It’s perhaps this lack of focus on people that makes the plot feel so distant, and the sudden change in direction that I remembered from my youth wasn’t quite as shocking, obviously in part because I knew it was coming, but also because you can put the pieces together long before Grushko’s rouble finally drops. And yet it’s not really a clewed mystery, as many aspects of what occurs don’t tie into the plot at all: the adversary is never more specific than “the Mafia”, as if that itself is a sentient beast to be tamed, and each crime is committed by “the Mafia” with very little focus on acts by individuals until it turns out someone was seen at a crime scene and so becomes the focus of the next few chapters. Nevertheless, I remember vividly the impression this had on me as someone venturing into a genre, and it has stood out i my mind all these years as an example of how what starts of as a ‘simple murder’ can fit into a far more complex and surprising scheme come the end — a salutary lesson in the delights that awaited in GAD.

Not what I’d hoped, then, and by no means the usual sort of thing that finds itself talked about on here, but possibly a better experience as a result.

~

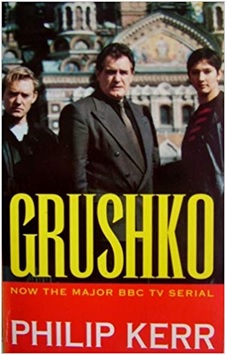

This was filmed by the BBC and shown in 1994 under the title Grushko, with the incomparably wonderful Brian Cox as the eponymous investigator — that’s him in the middle on the tie-in paperback cover above. I’ve never seen it, but would be semi-interested to see how they adapted it and how much was retained for the screen. Certainly there’s nothing here that would be problematic from a budget, political, or moral perspective, and it’d be worth seeing how the spirit of the piece was either upheld or shifted over for TV. One of these days, perhaps…

~

Going Home on The Invisible Event:

Fade Away (1996) by Harlan Coben

Blood Work (1998) by Michael Connelly

Angels Flight (1999) by Michael Connelly

Dark Hollow (2000) by John Connolly

The Monkey’s Raincoat (1987) by Robert Crais

Airframe (1996) by Michael Crichton

Dead Meat (1993) by Philip Kerr

A Drink Before the War (1994) by Dennis Lehane

Black and Blue (1997) by Ian Rankin