I am reliably informed by the product page on Amazon that I purchased the Kindle edition of The Fourth Door (1987, tr. 1999) — the first Paul Halter novel I ever read — on 19th May 2013. After nearly 6 years, 14 novels, 19 short stories, and 30 blog posts that included a celebration of his 60th birthday I’m going back to the beginning to see where it all began.

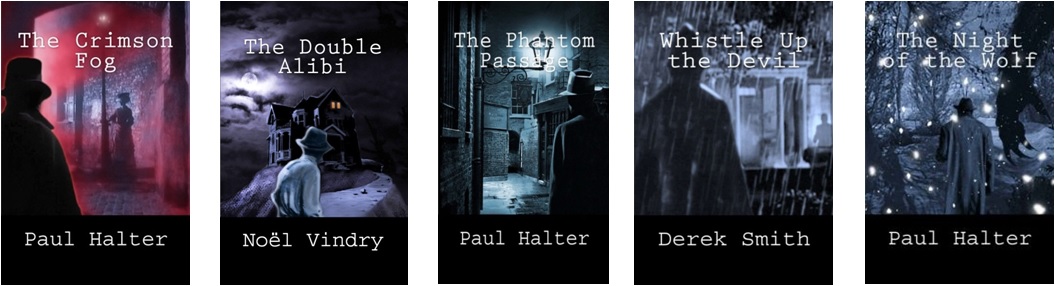

As well as being my own introduction to Halter, The Fourth Door was Halter’s introduction to the world as a wrangler of impossibilities. Both undertakings have endured — Halter proving to be amply capable of some staggeringly inventive reasoning when trying to get the impossible to happen, and me hoovering up with joy every word John Pugmire is able to put into a form that my simple brain can process. Since we’re talking about beginnings, the Locked Room International edition was also the beginning of an occasional trend in their covers, namely A Man in a Hat Looks into the Middle Distance:

The plot of The Fourth Door is astonishingly difficult to summarise, not merely for the simple reason of spoilers but because making the series of events that occur in the first half sound like a cohesive, structured narrative is nearly impossible. This is something we’d see again from Halter — c.f. The Madman’s Room (1990, tr. 2017), The Man Who Loved Clouds (1999, tr. 2018) — and this reread has brought back a lot of memories of the uncertainty I felt at precisely what the focus of the impossible crime plot was going to be. I mean, the plot summary on the back cover begins thus…:

Someone has volunteered to spend the night in the haunted room at the Darnley House. The room is sealed by pressing a unique coin, selected moments before, on the wax. But when the door is re-opened, someone else’s body is lying there, the seals are unbroken, and the coin has not left the possession of the witness.

…but we’re about halfway through before that occurs, by which point we’ve already had (deeeeep breath): the locked-room possibly-not-a-suicide of Mrs. Darnley behind the eponymous door to an attic room several years before, lights appearing in a room no-one goes into, a man having a premonitory dream about his mother’s death, a séance in which a message in a sealed envelope is read and responded to, ghostly footprints in an empty room, and the appearance of the same man simultaneously in London and Oxford. The swapped body behind that same door to a room rendered impossible to access then occurs on page 64 of 156 (!) and (I shall preserve the surprise) ten pages later we get another revelation that manages to cast any preconceptions you’ve managed to jump to into new doubt.

First time around, I recall it being a bit ADHD, but with possibly hundreds of hours reading, and thinking and writing about, Halter’s approach to the impossible crime I have to say that on second reading I was almost hooting for joy at times (that second revelation I hint at in the above paragraph, I’d entirely forgotten that and holy hell it’s magnificent). Additionally, many of the earlier events are passingly justified by our narrator James Stevens at the start of the second section of the book, and his speculative explanations strike a certain chord in how common sensical they are: grief plays a part, as does opportunism, as does simple greed. Indeed, I wasn’t entirely sure whether those explanations would end up being overturned by the end, or whether there would be a shrug and a narrative “Yup, that’s pretty much it” on page 152. Indeed, at each new stage of mystification Halter is able to offer up — either via James Stevens or the increasingly exasperated Inspector Drew — explanations or considerations of events that sound reasonably fair, and only seem to be undone by simple trifles that could themselves have been faked. So the revelations could be how something previously considered wrong was in fact right, and the disproof was where the error crept in.

I didn’t know, I’d no experience of Halter to base this on, but I was very much feeling my way without a huge amount of insight on what to expect. Was Halter genuinely adept in the wrangling of the impossible crime — those three words J____ D________ C____ linger so close to the surface whenever a comparison is made, and I was both determined and unwilling to believe it — or was he simply another poseur who had gotten lucky with some adept marketing? A lot of mystery novels are “in the style of Agatha Christie”, after all, and wouldn’t be fit to baffle Arthur Hastings. And for all the whirligig of explanation and counter-explanation, there was one key aspect of events that Halter was very squarely not looking at and clearly hoping we’d forget which simply had to be the solution for the body-swap and, honestly, left me rather underwhelmed. I remember much of my reading being powered by background impatience, a finicky repeated refrain of “Yeah, okay, let’s just get to that obvious answer…”.

I didn’t know, I’d no experience of Halter to base this on, but I was very much feeling my way without a huge amount of insight on what to expect. Was Halter genuinely adept in the wrangling of the impossible crime — those three words J____ D________ C____ linger so close to the surface whenever a comparison is made, and I was both determined and unwilling to believe it — or was he simply another poseur who had gotten lucky with some adept marketing? A lot of mystery novels are “in the style of Agatha Christie”, after all, and wouldn’t be fit to baffle Arthur Hastings. And for all the whirligig of explanation and counter-explanation, there was one key aspect of events that Halter was very squarely not looking at and clearly hoping we’d forget which simply had to be the solution for the body-swap and, honestly, left me rather underwhelmed. I remember much of my reading being powered by background impatience, a finicky repeated refrain of “Yeah, okay, let’s just get to that obvious answer…”.

Oh. Ye. Of. Little. Faith.

I’m getting a little ahead of myself because on rereading this, with a fair-to-moderate sense of what’s forthcoming (the precise details eluded my memory, including me remembering the false solution for the second murder as the true solution), I now appreciate just how damn tidily this book is put together. The solutions obviously intrigued me first time around, or it’s unlikely I would have read further, but if you’re picking this up as your first Halter, the best advice I can give you is to put your confidence just ahead of your doubts: the man knows what he’s doing in the main, even if some elements do underwhelm. But, yeesh, I was going to attempt to provide a plot summary, so let’s do that. Sorry, this is all pouring out in a breathless rush because I’m so thrilled at having found this such a good fun second time around; my editorial eye is all over the place at the moment.

Broadly, the plot of The Fourth Door centres around James Stevens, nineteen years old when the book begins, and his two set of neighbours the Darnleys and the Whites. It is Victor Darnley’s wife who was found covered in stab wounds and with both wrists slit in the bolted room at the top of their house some 10 years before our narrative opens, and rumours of a haunting presence in the house have persisted ever since: try as Victor Darnley might, he cannot get anyone who rents out the upper two floors of his house to stay for any length of time — unusual noises and lights from the attic inevitably drive them away, and he and his son John are simply resigned to a stream of short-term rents before the next people move in.

At the start of the book, James’ sister Elizabeth beseeches him to go and speak with Henry, the son of their other neighbour, the famous doctor-turned-author Arthur White, since she has ‘set her cap’ at young Hank and is finding his awkwardness around her vexing…to such an extent that she is considering the approaches of young John instead. It is during this evening, after putting away far more hard liquor than two 19 year-olds could reasonably be expected to manage, that Henry apparently dreams of his mother’s death and is phoned minutes later and informed that it has come to pass. Shortly thereafter, Patrick and Alice Latimer move into the Darnley house, a notable event since Alice is a medium of some repute, and at their earliest encounter with Arthur White she is able to perform the message-in-an-envelope routine in almost blissfully atmospheric conditions, and slowly Arthur’s conviction in her ability to contact the dead begins to grow.

At the start of the book, James’ sister Elizabeth beseeches him to go and speak with Henry, the son of their other neighbour, the famous doctor-turned-author Arthur White, since she has ‘set her cap’ at young Hank and is finding his awkwardness around her vexing…to such an extent that she is considering the approaches of young John instead. It is during this evening, after putting away far more hard liquor than two 19 year-olds could reasonably be expected to manage, that Henry apparently dreams of his mother’s death and is phoned minutes later and informed that it has come to pass. Shortly thereafter, Patrick and Alice Latimer move into the Darnley house, a notable event since Alice is a medium of some repute, and at their earliest encounter with Arthur White she is able to perform the message-in-an-envelope routine in almost blissfully atmospheric conditions, and slowly Arthur’s conviction in her ability to contact the dead begins to grow.

Jump forward three years. Henry has disappeared, presumably to America, having first been seen in two places at once following suspicion of a crime falling upon him, and his father, ever under the spell of the Latimers, consents to an experiment that it is hoped will bring him into contact with his dear departed wife:

“One of us is going to stay in the haunted room. Naturally the room will be sealed. Every half-hour I shall go up and knock on the door to see if everything is all right. We shall need a trustworthy witness when the seals are removed so as to avoid the suspicion of trickery if the spirit does indeed materialise in one fashion or another.”

Here, finally, is where the threads begin to knit together, and a scheme emerges that will find apparently the wrong man dead and all manner of complications yet to be resolved. A second murder, in a house surrounded by unmarked snow, will also present itself, and to an extent I can understand my feeling of ADHD from the original experience of reading this since it really does seem a Herculean task not to prescind from certain occurrences within the plot purely to keep an eye on what’s happening in any given brace of chapters. And just to add to the fun, this is where Halter’s fanboy hat comes out and, along with the above arrangements recalling the likes of the room-that-kills problem in the sublime The Red Widow Murders (1935) by Carter Dickson and Arthur White’s own medicine-to-writing-to-spiritualism path matching Conan Doyle’s trajectory through reason and out the other side, we also get a character named John Carter (I’m assuming more a Dickson/Carr reference than an Edgar Rice Burroughs one…) and a treatise on the life and achievements of Harry Houdini before a staggering parallel is drawn that echoes one of Carr’s most controversial books (oh you know the one…).

And then, just as it beings to form some kind of pattern, with various explanations being drawn and then discarded, then Halter changes things dramatically in a way that both explains the seemingly over-stuffed nature of his book and also might come across to some as a bit of a lazy apology for it. There’s again previous here — think Jacques Futrelle — and I can see how the non-traditional nature of what emerges might frustrate some people, but given the higgledy-piggledy nature of what’s come before this is simply one more trick in the box, and if you were hoping for something a little less left-field then I imagine that’s precisely what Halter wanted you to expect. And in many ways this feels to me like the moment Halter really establishes himself — without this particular conceit this could be a notable and fun addition to the impossible crime firmament, but Halter is a game-player of broader talent and wants to make his first swing a little more memorable. While it’s true he would go on to produce more ‘standard’ fair of greater cunning — The Tiger’s Head (1991, tr. 2013), The Lord of Misrule (1994, tr. 2006), The Phantom Passage (2005, tr. 2015), etc — he would also exhibit as fixation with narrative that comes out superbly in some places, like The Picture from the Past (1995, tr. 2014), The Seventh Hypothesis (1991, tr. 2012), and short story ‘The Cleaver’.

And then, just as it beings to form some kind of pattern, with various explanations being drawn and then discarded, then Halter changes things dramatically in a way that both explains the seemingly over-stuffed nature of his book and also might come across to some as a bit of a lazy apology for it. There’s again previous here — think Jacques Futrelle — and I can see how the non-traditional nature of what emerges might frustrate some people, but given the higgledy-piggledy nature of what’s come before this is simply one more trick in the box, and if you were hoping for something a little less left-field then I imagine that’s precisely what Halter wanted you to expect. And in many ways this feels to me like the moment Halter really establishes himself — without this particular conceit this could be a notable and fun addition to the impossible crime firmament, but Halter is a game-player of broader talent and wants to make his first swing a little more memorable. While it’s true he would go on to produce more ‘standard’ fair of greater cunning — The Tiger’s Head (1991, tr. 2013), The Lord of Misrule (1994, tr. 2006), The Phantom Passage (2005, tr. 2015), etc — he would also exhibit as fixation with narrative that comes out superbly in some places, like The Picture from the Past (1995, tr. 2014), The Seventh Hypothesis (1991, tr. 2012), and short story ‘The Cleaver’.

The only real shame is that sometimes his answers are, as suspected during my first reading, the ones offered in speculation; the mysterious lights for one certainly could have been utilised in a slightly more compelling way, even if the aspects mentioned above — opportunism, greed, etc — do play perfectly into the picture he paints. Equally, the ghostly footsteps are explained, sure, but not in a way that you’d feel really evinces a gasp of “But, of course!” — rather more a raised eyebrow and a “Hmm, okay, sure”. Some of his answers are brilliant: the body-swap is ingenious, despite that needless distraction of the thing I was (incorrectly) certain laid bare the whole enterprise — it’s on page 69 of this paperback edition, see if you can recognise what I’m referring to — and the arc the Latimers fulfil is exquisitely plotted in both a narrative and meta-narrative sense; equally we don’t see much of Bob Farr, and you feel Henry is a little lucky to’ve found him and rather too touchy on the accusations made against his professional abilities as a result, but the way he plays into the wider scheme is nicely worked, and makes for a couple of superb moments.

Amidst all this fun, though, let’s not deny that some aspects go a little awry: the prophetic dream, and the solution for the no footprints murder (though I love the shenanigans with the _ _ l _ _ h _ _ e) are a little rushed over, as is Mrs. Darnley’s possible suicide. This element of how past events would inform present ones is something Halter would improve significantly in later works, as seen in the ways he would begin to work existing myths and legends into his works rather than relying on creating an entirely new backstory for his setups — c.f. The Invisible Circle (1996, tr. 2014), The Seven Wonders of Crime (1997, tr. 2005). And I think this was something he took away and learned very quickly: that your threads need to be tied up, that you try not to put too much in (an aspect of Halter’s writing that persists in his most ambitious novels) unless you can make the pieces fit (a hallmark of his most successful ones).

It’s also true that there’s very little in the way of ratiocination and detection — when Alan Twist eventually appears on the scene he does a little digging and is simply told some stuff, but most of what is unpicked is done so via confession or “Well, I imagine it happened like this” surmise. It’s true that there’s a faint French tradition of this evident in the French-language classics we’ve seen Locked Room International bring us since — both The House That Kills (1932, tr. 2015) and The Howling Beast (1934, tr. 2016) by Noel Vindry are long on confoundment and short on detection, seeing as someone either confesses or simply realises the truth — but I’ll defer to the greater experience of those who have read more widely in the detection roots of that culture whether this is a prevailing trend or simply an illustrative coincidence. This does leave space for a Pierre Bayard-style What Really Happened Behind the Fourth Door reinterpretation, however, so feel free to get your thinking caps on…

It’s also true that there’s very little in the way of ratiocination and detection — when Alan Twist eventually appears on the scene he does a little digging and is simply told some stuff, but most of what is unpicked is done so via confession or “Well, I imagine it happened like this” surmise. It’s true that there’s a faint French tradition of this evident in the French-language classics we’ve seen Locked Room International bring us since — both The House That Kills (1932, tr. 2015) and The Howling Beast (1934, tr. 2016) by Noel Vindry are long on confoundment and short on detection, seeing as someone either confesses or simply realises the truth — but I’ll defer to the greater experience of those who have read more widely in the detection roots of that culture whether this is a prevailing trend or simply an illustrative coincidence. This does leave space for a Pierre Bayard-style What Really Happened Behind the Fourth Door reinterpretation, however, so feel free to get your thinking caps on…

The Fourth Door, then, is a wildly creative, flawed work whose promise has been fulfilled in the works of Halter’s we’ve seen cross the language barrier. It was a blast rereading this and remembering the anticipation and relief I felt when the best answers finally arrived, and the little niggles that persist come the end have arguably been addressed in those later works. Indeed, some of those later books I would consider stone cold classics of the genre, and each new translation has simply been further fuel to raise my excitement for the next. After 32 years this stands up as the opening salvo of a career that’s worked hard to sustain originality in the hardest game in the world, and I’m fascinated to see how those three decades of experience contribute to The Gold Watch (2019) due later this year.

~

Paul Halter reviews on The Invisible Event; all translations by John Pugmire unless stated

Featuring Dr. Alan Twist and Archibald Hurst:

The Fourth Door (1987) [trans. 1999]

Death Invites You (1988) [trans. 2015]

The Madman’s Room (1990) [trans. 2017]

The Seventh Hypothesis (1991) [trans. 2012]

The Tiger’s Head (1991) [trans. 2013]

The Demon of Dartmoor (1993) [trans. 2012]

The Picture from the Past (1995) [trans. 2014]

The Vampire Tree (1996) [trans. 2016]

The Siren’s Call (1998) [trans. 2023]

The Man Who Loved Clouds (1999) [trans. 2018]

Penelope’s Web (2001) [trans. 2021]

Featuring Owen Burns and Achilles Stock:

The Lord of Misrule (1994) [trans. 2006]

The Seven Wonders of Crime (1997) [trans. 2005]

The Phantom Passage (2005) [trans. 2015]

The Mask of the Vampire (2014) [trans. 2022]

The Gold Watch (2019) [trans. 2019]

Standalones:

The Crimson Fog (1988) [trans. 2013]

The Invisible Circle (1996) [trans. 2014]

Collected short stories:

The Night of the Wolf (2000) [trans. 2004 w’ Adey]

Individual short stories [* = collected in the anthology The Helm of Hades (2019)]:

‘Nausicaa’s Ball’ (2004) [trans. 2008 w’ Adey]*

‘The Robber’s Grave’ (2007) [trans. 2007 w’ Adey]*

‘The Gong of Doom’ (2010) [trans. 2010]*

‘The Man with the Face of Clay’ (2011) [trans. 2012]*

‘Jacob’s Ladder’ (2014) [trans. 2014]*

‘The Wolf of Fenrir’ (2014) [trans. 2015]*

‘The Scarecrow’s Revenge’ (2015) [trans. 2016]*

‘The Fires of Hell’ (2016) [trans. 2016]*

‘The Yellow Book’ (2017) [trans. 2017]*

‘The Helm of Hades’ (2019) [trans. 2019]*

‘The Celestial Thief’ (2021) [trans. 2021]

‘The Wendigo’s Spell’ (2023) [trans. 2023]

Congrats for 500 posts!

LikeLike

Many thanks, here’s to another 30 or so… 😛

LikeLike

500 is amazing! Why, it only seems like yesterday … bravo!

LikeLike

You’re telling me — not entirely sure how I’ve managed ot hang around this long, to be honest. But it’s fun, so I’ll keep stinking the place out for a while yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, when the youngsters grow up… Congrats on 500 posts, JJ. Keep up the good work.

LikeLike

Feel like Facebook would have an algorithm-selected sample of my highlights. WordPress is decidedly more casual — “Woo, you’ve posted 500 times”, no need to get too excited, much more my style.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s to your next 500! I’ll be dipping my toe into Halter soon as I’ve got “The Night of the Wolf” on order.

LikeLike

If you’re not acclimatised to Halter and his ways, those stories give a good flavour. Some masterpieces in that collection, to my way of thinking, will be really interested in your take when you get there.

LikeLike

Congratulations on hitting the 500 mark! I plan to delve a little deeper into Halter’s stuff later in the year.

LikeLike

Huzzah!

LikeLike

“…and wouldn’t be fit to baffle Arthur Hastings.” I like this as a standard response to any sub-par book.

LikeLike

Congratulations, or should that be deduct-u-lations, on reaching this blogging milestone! I’m sure the road to a 1000 posts will be even more fascinating and interesting.

And remember… you promised us to dig up at least one really obscure locked room mystery!

LikeLike

Er *sweats profusely* no, that was, uhm, Brad who said that. Uh *scans bookcase* I’d never make such a claim…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did the math, and I will catch up to your number of posts in only three weeks!!!

Wait a minute . . . three times seven . . . carry the two. . . . . .

Who the heck was my math teacher?

Congrats on Five Hundred Posts, JJ. Like you, TFD was my first Halter, and I’ve read all the translations. It has been a fascinating road, partly for spotting the differences in what you and I look for in a mystery. But it has been a fun road to travel with you, the spectrum of opinion between us has lessened, and best of all – it continues!! Maybe the cretins above who all say, “I plan to explore Halter later this year after this and that and the other” can get off the stick and join us.

Golden Watch, here we come.

LikeLike

Your persistence is to be admired, Brad — but at least when we agree on Halter’s merits we are finding common ground on what he does well. And, crucially in rereading this, I’ve realised how he’s actually worked very hard to cover over some of the gaps in his approach that, if left untended, might have opened into unbridgable chasms.

LikeLike

Congratulations on hitting this milestone JJ!

I enjoyed reading this review a lot though this is one of the (still far too) many gaps in my Halter reading. It sounds, like many of his works, like quite an exciting and inventive piece, even if some of the elements seem a little disjointed. I will look forward to revisiting this review once I read it myself to pick up on all of those mysterious words with the letters deleted!

LikeLike

Well, you’ll definitely enjoy the _ h _ e _ _ _ _ d _ m _ _-R _ _ _q_ tt _ ppp. And if you don’t., there’s something wrong with you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations, JJ! I’m precluded on expressing any opinions I might have on The Fourth Door in the face of your achievement! Your takes on books are always enjoyable to read, and it’s thanks to you that my interest in mystery novels has grown over the past few years (at least, I think so… I’m not actually that sure how it all happened). My introductions to Carr, to Berrow, to Crofts, are all thanks to you. I hope to read many more of your reviews to come, and thank you for writing them.

LikeLike

Many thanks — I’m very fortunate to have such an engaged, knowledgeable readership who a) don’t let me get away with lazy nonsense, and b) seem to enjoy my various meandering approaches. It’s always a pleasure to talk about this stuff I love with people who are as enthusiastic…let’s keep going for a while yet!

LikeLike

Congratulations! Here’s to the next 500 and beyond!

LikeLike

Cheers, Rob — and thanks for taking my particular obsession so seriously. Hope all’s going well with the new book 🙂

LikeLike

You have me desperately wanting to tear into this book. I have to abstain from Halter for at least another month, lest I blow through his catalogue, but The Fourth Door is definitely a candidate for a next read. I have enough experience with Halter to know that even if the story has a few flaws, it’s still going to be a top read.

LikeLike

I wonder if you’ll pick up on the false-solution-that-wasn’t which bothered me so much when I first read this. Man, I want to know what others make of that. But, well, all in good time…

LikeLike

Gratulerar!

I really should be re-reading Paul Halter some day – I find that I’ve forgotten most of the plots. (Apart from the one that disappointed me most, The Crimson Fog. But maybe that means I can skip that one?)

One slight problem with that is all the OTHER things I want to re-read, and the fact that I have seven or eight Halters lying around that I haven’t read for the first time yet. Argh.

LikeLike

Tack sa mycket!

What a lovely problem to have — in order for me to get to that situation I must first spend at least a couple of years improving my French. Which I’ve been meaning to do for about 10 years now.

Okay, you’ve made me finally sit up and take notice — 2019 is finally going to be the year I actually do this. Or start doing it, at least…

LikeLike

Keep up the great work, JJ. The first 500 posts are the hardest, they say. I send the master everything you write about him and he is greatly appreciative

LikeLike

Happy 500th! You don’t look a day over 90.

LikeLike

…and I don’t feel a day under 700.

LikeLike

Congrats on the milestone! At my own rate of posting, I should match this sometime in the next century as you celebrate post 3000,

As for the book, I admit that I am one of those who was annoyed by the twist you talk about.

SPOILERS FOLLOW!

My issue was that I got invested in the characters and was genuinely caring about them, and then that twist completely jarred me out of it. Even thought the setting was so thin in places I actually forgot this was et in a village, and not in three houses in the middle of nowhere. I know that it technically gets reversed later, but it was a little too late then. And that last twist…I almost threw the book across the room, but thankfully I’m too cautious about my books. I don’t know why it annoyed me so much, honestly. Maybe I just liked Stevens a little too much and thought it raised more questions than answers.

I liked how badly Inspector Greg bungled the whole thing,which was certainly an interesting play on the Lestrade character, and the solutions were good. Still not 100% sure on the second, but I can accept it.

LikeLike

I’m with you on the setting — I mean, it pretty much does takes place in thee houses and some implied woodland. I didn’t mind that myself, it helps the claustrophobia of the setup, and the mention of railway stations or other settings work in well without distracting from the simplicity of what you’re actually shown.

As for the characters, I always enjoy a conceit that throws any preconceptions for a loop — I mean, the ending of The Player of Games by Iain M. Banks still riles me 20 years after I first read it, but I have to acknowledge its effectiveness in what it’s trying to do (and, therefore, does). This is the same idea, and the reversal is reversed, as you say, which I also loved, though othersmay not. It’s just the inventiveness I like, I think, and the game-playing is pretty much at peak in how it drags you first one way and then the next.

Not everyone goes for it, though. I entirely understand.

LikeLike

Happy Birthday friend. I like the idea of ADHD meaning: A Detective Halterian Disorder

LikeLike