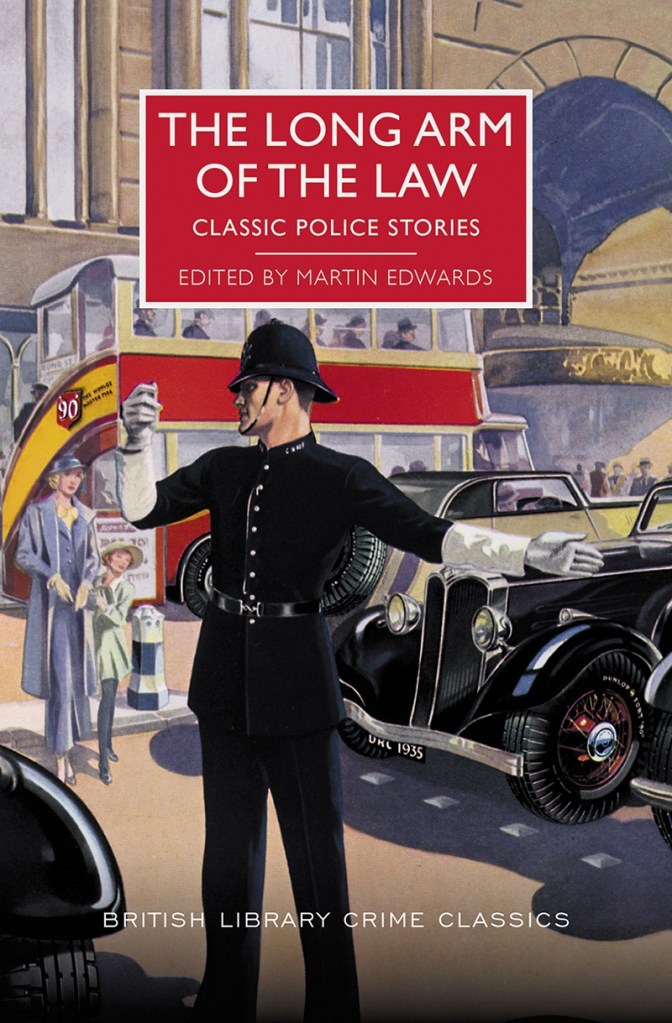

An earlier British Library Crime Classics short story collection today, with The Long Arm of the Law [ss] (2017) featuring 15 stories of professional police selected by the hugely knowledgeable Martin Edwards.

Like, I imagine, a lot of GAD readers, I was drawn to the genre by the histrionics of private investigators like Hercule Poirot and Dr. Gideon Fell. I have, however, in recent years, in no small way thanks to the efforts of Freeman Wills Crofts, Rupert Penny, and others, come to appreciate the professional copper, often grinding away at something with a tenacity that is, if anything, more impressive to me than the dilettante’s sudden rush of blood to the head. So a belated visitation upon the contents of this was something I anticipated quite keenly.

“I fear that Mr. Darrell is poisoning his wife,” says the butler Grimsby in ‘The Mystery of Chenholt’ (1908) by Alice & Claude Askew, and so Police Constable Reggie Vane sends his fiancée Violet Grey in to investigate. Given the era in which this was written, it’s not surprising that the whole thing is less than completely rigorous or rational, but it’s fun and quick and difficult not to enjoy, and the final line is quite wonderful in its own way.

‘The Silence of PC Hirley’ by (1909) by Edgar Wallace concerns “the most famous blackmailer in the world” — who knew there were rankings of these things…? — and the eponymous laconic policeman who is, very tangentially, involved in a case of murder involving said bastard. Wallace is going for subtlety here, never his strong point, and it doesn’t quite come off, but, at the same time, it’s rather pleasant to finish the story and fill in some of the gaps left behind. Unusual, and notable for that.

I was first introduced to George R. Sims and his lady detective Dorcas Dene in The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime [ss] (2011) edited by Michael Sims. ‘The Mystery of a Midsummer Night’ (1911) is a tale told by Detective Inspector Chance concerning the murder of a four year-old boy, and as detection goes it’s absolutely among the worst things I’ve ever read. Not only is the key clue ‘Someone went to a place once’ — yeah, no, I’m not joking — but if you’ve hidden something somewhere “where nobody found it” then how is the hiding of that thing in the telling place public knowledge? Sorry, George, but this is crap.

Laurence W. Meynell has popped up in a handful of places in my GAD reading, but never really seems to make that much of an impact, and ‘The Cleverest Clue’ (1937) demonstrates why. No doubt the clue brought to ex-Inspector Joseph Morton, late of the C.I.D., by which the whereabouts of a kidnapped engineer can be deduced, is clever, but it relies on such a specific piece of good fortune that it sort of eradicates its own cleverness, since the situation is designed purely so that this can be a clue. Still, some good phrasing…

[T]his tiny little hamlet where the Saunders lived really was off the map. A man could have murdered his mother-in-law there, slowly and scientifically, and even if she had screamed her silly head off nobody would have been any the wiser.

…earns Meynell points even if his ideas aren’t as ingenious as the title suggests.

‘The Undoing of Mr. Dawes’ (1935) by Gerald Verner is a spry tale featuring his Superintendent Robert Budd, who must contend with the eponymous Mr. Dawes, an outwardly-respectable fence. I’ve not encountered Budd before, and Verner falls into Wallace’s class in my mind in that he’s often good with striking characters and a turns of phrase, but falls down on constructing plots. On this evidence, with those caveats in mind, this was clever in a minor way and I would definitely make Budd’s acquaintance again. So watch this space.

A return trip for me to Roy Vickers‘s Department of Dead Ends with ‘The Man Who Married Too Often’, a.k.a. ‘Molly the Marchioness’ (1936). Something about reading that above-linked collection broke Vickers for me, so that, while I enjoy his cattiness (“She did not know who her father was; nor, one is bound to believe, did her mother.”), the excess of redundant detail in his stories feels like being regaled by a blustering Major who can’t remember what his next sentence was going to be. I’d happily never read Vickers again, I think.

Detective Inspector Anthony Slade investigates ‘The Case of Jacob Heylyn’ (1933) by Leonard R. Gribble, in which our eponymous miser is found shot in his study in a clear case of suicide. No locked door, alas, but everything else on hand to make it clear that Heylyn did himself in…and so, of course, that can’t be what happened.

There’s a clever idea here — “Ever known any one let somebody else stick a loaded gun into his mouth without protesting?” — but the answer is more interesting than the frankly tedious story that leads up to it. Goes to show how lucky we were with the like of John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, and others who could put a clever idea like this into a context that was also enjoyable to read. We should not take that for granted.

‘Fingerprints’, a.k.a. ‘Flaw in a Masterpiece’ (1952) by Freeman Wills Crofts was included in The 9:50 Up Express [ss] (2022), but time spent with Crofts is rarely wasted and so I was more than happy to read it again. And this short inverted story of a criminal who “left proof that the elaborate suicide he had staged was no suicide at all, but wilful murder” is neatly tied up with an unshowy deployment of negative evidence, perhaps my favourite for of evidence. Lacking in Crofts’ usual rigour, perhaps, but difficult to object to.

One sympathises with the Norfolk bobby who hangs out in London pubs “to get accustomed to the sound of East End cockney, which he found hard to understand” in ‘Remember to Ring Twice’ (1950) by E. C. R. Lorac. The principle here is good, but it turns on a sort of John Rhodeian death trap that I found impossible to envision and so just had to assume would work as Lorac tells us.

Henry Wade‘s lesser known Detective Constable John Bragg features in ‘Cotton Wool and Cutlets’ (1940), which benefits from Wade’s typical economy with illustrative phrasing:

A uniformed constable was trying his best to disperse the crowd, but death is an unfailing draw.

This would actually have made for an excellent entry in Six Against the Yard (1936) if only the killer had (rot13 for spoilers) jnvgrq sbe gurve ivpgvz gb rng uvf qvaare svefg. Wade’s good value here, and it serves only to make me wish even more fervently for someone to reprint his novels in the high quality, affordable paperback editions I’m convinced they deserve.

An interesting repeat within the BLCC series next, with ‘After the Event’, a.k.a. ‘Rabbit Out of a Hat’ (1958) by Christianna Brand being reused by Edwards in the later Final Acts [ss] (2022) collection. This would have been my fourth time reading this (very good) story, so head there for what are most likely still my thoughts on it.

I’m yet to be convinced of the criminous literary merits of Nicholas Blake, and ‘Sometimes the Blind…’ (1963) does little to enhance him in my estimations. It’s…fine, but beyond a sort of nebulous idea that you can’t charge someone without evidence there’s little here to get too interested in.

Equally, ‘The Chief Witness’ (1957) by John Creasey, which will be one of 64,217 stories Creasey wrote that particular month. It’s not bad, but there’s nothing especially good about it beyond the opening told from the perspective of an uncomprehending child. Once that device is abandoned, there’s really nothing here that warrants any interest, no clever idea, no shocking reversal. It’s Creasey, and fulfils expectations in that regard, but that’s all.

A hit-and-run on a popular local confectioner with “a soft heart and a bad memory” starts Detective Inspector Patrick Petrella on a case in ‘Old Mr. Martin’ (1960) by Michael Gilbert, with an older crime uncovered and some solid procedural work on the way to clearing that up. A couple of good developments mark this out, and add to my impression that, despite finding his novels rather meh, Gilbert is probably more in my line where his short fiction is concerned. Expect developments.

To finish, I don’t know quite what to make of ‘The Moorlanders’ (1966) by Gil North. The staccato telling is an interesting stylistic choice, North jumping between scenes without any transitional explanatory scenery, and it makes the whole affair feel more consequential than it is. I’d have left this out, or found something of a little more import, but I can see why it appealed to Edwards, since it stands so very far stylistically from everything else herein.

As has become custom, a top 5:

- ‘After the Event’, a.k.a. ‘Rabbit Out of a Hat’ (1958) by Christianna Brand

- ‘Cotton Wool and Cutlets’ (1940) by Henry Wade

- ‘The Silence of PC Hirley’ by (1909) by Edgar Wallace

- ‘Old Mr. Martin’ (1960) by Michael Gilbert

- ‘The Undoing of Mr. Dawes’ (1935) by Gerald Verner

This is an interesting selection of stories from some often unheralded writers, and as such shows why these collections Edwards edits remain such a huge draw for readers. That said, I’d probably place it in the lower echelon of the BL collections I’ve read to date since, despite an appealing variety of styles and approaches, there’s not much that stands out, and little — beyond the Brand, now available elsewhere — that really compels.

Nevertheless, these collections remain a wonderful opportunity to sample the works of authors who have faded from view, so rich were the pickings in the Golden Age, and we can be very grateful that Edwards’ characteristically scrupulous coverage of the genre shines a light in these corners that so many of us would otherwise merely blunder past unaware. It’s also worth considering that this particular theme might bear re-exploring in the years ahead, since there are doubtless still heaps of stories featuring professional coppers out there; I look forward to that possibility, as well as getting my teeth into the various collections in this series that I’ve still not sampled.

~

British Library Crime Classics anthologies on the Invisible Event, edited by Martin Edwards

Capital Crimes: London Mysteries (2015)

Silent Nights: Christmas Mysteries (2015)

Crimson Snow: Winter Mysteries (2016)

Continental Crimes (2017)

Foreign Bodies (2017)

The Long Arm of the Law (2017)

Final Acts: Theatrical Mysteries (2022)

Crimes of Cymru: Classic Mystery Tales of Wales (2023)

Who Killed Father Christmas? and Other Seasonal Mysteries (2023)

As If by Magic: Locked Room Mysteries and Other Miraculous Crimes (2025)

Oh hey, one I’ve read. Lots of overlap in our top five, I liked ‘Cotton Wool and Cutlets’ and ‘The Undoing of Mr. Dawes’ less, ‘The Man Who Married Too Often’ and ‘Sometimes the Blind’ more.

My real criticism was that I didn’t feel this collection fulfilled its remit. ‘The Mystery of Chenholt’ could have featured a private detective as easily as a cop, ‘The Cleverest Clue’ isn’t about a policeman it’s about the friend of the victim, the Department of Dead Ends is virtually a deconstruction of police methods, ‘After the Event’ (which I love) does not show policework, ‘The Undoing of Mr Dawes’ even jokes that it doesn’t use real police methods … since I, like you, came to the genre through its Great Detectives I was hoping for more of a look at actual policework.

LikeLike

You make some excellent points, and I can’t deny that there is definitely scope for another “professional police” collection that would fulfil the brief perhaps more fully. Maybe there’s one in the works — who knows?

What to call it, though? Policeman’s Lot has already been taken, so perhaps Laying Down the Law? Caught by the Fuzz? Answers on a postcard…

LikeLike

I’m like 99% sure I’ve read this collection but have zero memory of it, which makes me not super surprised that you don’t particularly rate it… what DID surprise me is seeing that you overall dislike Michael Gilbert, which really surprised me as while he can on occasion fall into some dumb thriller tropes I tend to really like him (I really enjoy Smallbone Deceased and was surprised to see you find it boring, though I admit that Henry Bohun is a bit overly convenient). Then I clicked further and discovered that you DID like Death in Captivity, and thereby are proved to have taste lol.

(Some actually quite recent nostalgia associated with that one- I read it a couple of years ago and loved it, and while I caught a couple of clues and was more shocked than actually surprised by the final twist, Gilbert definitely got a lot over me. I then gave it to my 91-year-old grandfather, who I should have remembered had been reading/listening to/watching mysteries for the last 85 years, and by around chapter 2 he not only had identified the killer but had identified clues Gilbert laid that I hadn’t even noticed- in the “only x could have possibly known about y” vein, at a point when I’m not even sure the significance of y was clear yet. It was genuinely a bravura performance from my grandfather, who passed away not long afterward, and a memory I’ll always treasure.)

Re possibly preferring Gilbert’s short stories- I HIGHLY recommend you check them out! I just read his The Man Who Hated Banks and there were some excellent stories in there. His introduction, to be honest, made me a bit nervous as it felt like him in a bit more thriller mode, but actually I had a fantastic time throughout. Not all are actually mysteries- some are more slice of life in a crime-y sort of way- but they’re all super enjoyable.

LikeLike

My reading of Gilbert has not yet reached the highs of that initial experience of The Danger Within — I tried and gave up on Smallbone Deceased, Close Quarters, Game without Rules, and possibly something else…and I wonder if I’m just not going to click with most of his work, y’know?

I really enjoyued one of his Petrella stories in another BLCC collection, and have the Young Petrella collection that I should really start reading at some point. I’ll put The Man Who Hated Banks on the list, too, and keep an eye out for a copy — thanks for bearing with me in my continued denseness!

LikeLike

Oh, I can totally imagine starting with Death in Captivity/The Danger Within (had no idea that was an alternate title til just now) making any other book of his seem lesser! I’d already read and largely enjoyed Smallbone Deceased and Death Has Deep Roots (though I kind of wish the latter had just been a courtroom drama as the French thriller stuff wasn’t particularly thrilling or relevant), so in contrast I was just wowed by Death in Captivity. But yes, definitely check out The Man Who Hated Banks, there’s a very fun assortment of stories in there (some Petrella, some Henry Bohun, some with some other policeman whose name I don’t recall, and a really interesting trilogy with a cop who turned bad that I’d expected to hate but really didn’t in the end) and some people ARE just better in the short form (I could go my whole life without ever reading another Clayton Rawson novel but I love his short stories).

EXTREMELY random Gilbert suggestion, actually- I have no idea if you’re one of those golden age fans who’s also into the 19th/early 20th century true crime that inspired the writers, but Gilbert (who of course was a solicitor himself) wrote an excellent write up of the Tichborne Claimant case that I thought was fascinating.

LikeLike

Thank-you for understanding!

I actually know very little about a lot of the true crime that influences GAD, and am pretty ignorant of even the fundamentals of, say, the Tichborne case, so that sounds like it could be a good read.

Oh, it doesn’t seem to have been reissued in the last, like, 70 years. This might take a while.

LikeLike

I actually learned of the writeup from the Shedunnit podcast as Caroline Crampton drew a lot of her Tichborne episode from the book- it was a good episode but an even better book! I got it from interlibrary loan, which is where I get most of my GAD-type books from… this one actually came from my state’s law library which was quite cool!

Another excellent book if you decide you’re into reading about GAD-related true crime- The Anatomy of Murder* is a compilation issued by the Detection Club which features GAD authors like Anthony Berkeley, Dorothy L Sayers, and Margaret Cole doing writeups of classic cases, some solved and some unsolved, some foundational to GAD literature and some just random interesting cases- pretty much all of them inserting some of their own personality and views into both their choice of subject as well as their treatment of the case. Margaret Cole’s choice of case given her marriage, and Anthony Berkeley’s choice of case given his, um, views of women, were both fascinating. (Like, I’d wondered if Berkeley wrote Jumping Jenny after being inspired by writing his essay on the Rattenbury case but turns out the Rattenburys were both alive and well when Jumping Jenny was published…) Also acquired by me through ILL so I have absolutely no idea of its general accessibility…

*I just watched the amazing movie Anatomy of a Murder which made getting the title of this one correct quite difficult lol

LikeLike

Yes, I remember Anatomy of Murder being republished here in the UK, and not thinking it was my thing at the time. Now, though, I can definitely see the appeal of it, so thanks for the reminder.

LikeLike