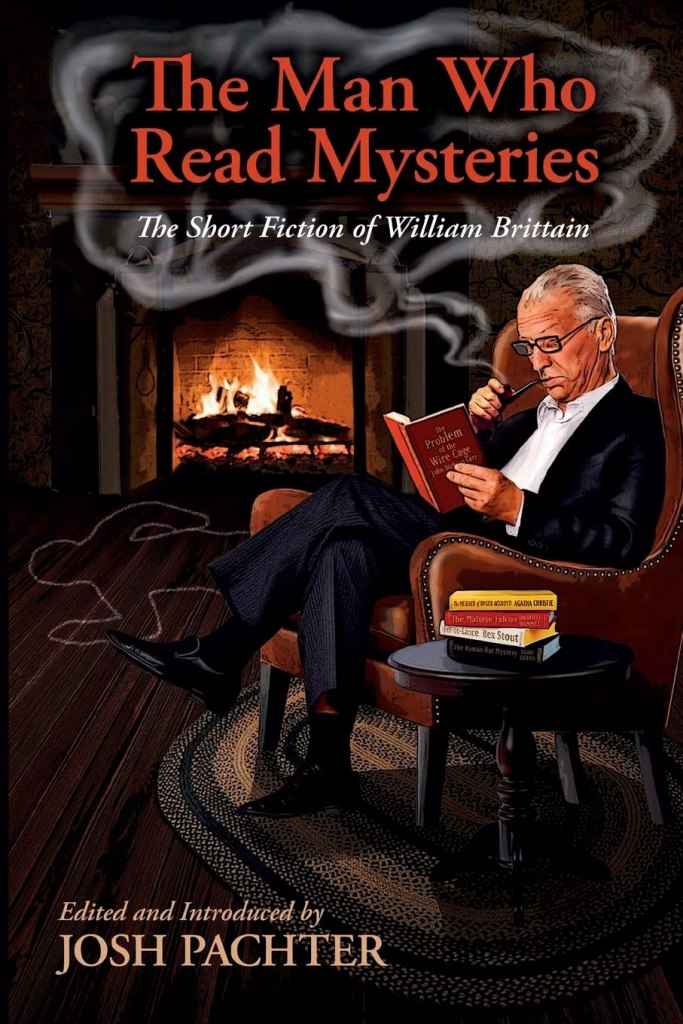

The first of (so far…) two volumes of William Brittain’s short fiction from Crippen & Landru, The Man Who Read Mysteries (2018) contains the eleven stories written under the non-series ‘The X Who Read [Author Name]’ titles and seven selections from editor Josh Pachter of the tales featuring crime-solving high school science teacher Leonard Strang.

Prior to this collection, I’d read just two stories by Brittain, ‘The Man Who Read John Dickson Carr’ (1965) and ‘Mr. Strang Accepts a Challenge’ (1976), the second in the Mike Ashley-edited The Mammoth Book of Locked Room Mysteries and Impossible Crimes [ss] (2000). I enjoyed both, and so the chance to revisit the first and see more from the same series as the second was to be seized with alacrity. Which is why it’s taken me, er, seven years since this was published to get round to reading it.

So, anyway, let’s dive in.

Is it fair to call ‘The Man Who Read John Dickson Carr’ (1965) Brittain’s most famous story? Maybe that’s an indication of my ignorance of his work more than anything else. Either way, its superb: chronicling the JDC obsession that grips a boy and feeds his imagination for a decade, after which he plans to “commit a locked-room murder that would mystify the master himself”.

Not only is this a genuinely great locked room story, it’s also a wonderful example of the crime writer’s art and ends with a final line kick that’s as surprising and brilliant as anything I’ve read in the short form for ages. Even knowing it was coming this time around, it still made me grin.

Equally brief and almost as effective is ‘The Man Who Read Ellery Queen’ (1965), which relocates to an old people’s home and concerns the theft of a valuable coin. Like Ellery Queen, the reasoning here is a little dubious, but it’s fun and light and throws in most of the necessary information effortlessly. Does beg one question — (rot13) Ubj pna n zna gnxr bss uvf gebhfref jvgubhg yvsgvat uvf srrg? — which stops me viewing this more positively, but it’s entertaining enough for what it is.

‘The Man Who Didn’t Read’ (1966) continues the pattern of small, tight puzzles, and an early plot point makes it fairly clear where this is going. We know by now that Brittain isn’t trying to write fair play mysteries, but the sort of genre-straddling take he adopts is, perhaps, even more interesting, as you watch in horror as each brick slides into place and the ignoramus of the title is pulled in by an almost Woolrichian sense of inevitability.

We find ourselves at the circus for ‘The Woman Who Read Rex Stout’ (1966), with a circus fat woman utilising her sidekick — the Thin Man, perhaps — to investigate the strangulation of another performer. This is…fine. I can’t fault it, and it sort of feels like a Rex Stout pastiche, but I’m not sure I felt too much about it while reading. I realised a few months ago how much I love a beach-set mystery; well, I’m starting to think that circus-set mysteries might be the ones that make me feel the most meh. That idea that anyone can be anything…I dunno, it doesn’t quite seem fair, y’know?

I love the setup of ‘The Boy Who Read Agatha Christie’ (1966), which sees a variety of college-age students descend upon a nearby small town and engage in a variety of bizarre behaviours: swapping articles round in the market only to put them back, or going from window to window at a bank changing and then re-changing an insignificant sum of money. It doesn’t feel especially Christie — it has more the playfulness of Anthony Boucher about it — but it’s great.

The reason for all this tomfoolery, too, is well-explained by the eponymous 10 year-old Belgian boy who idolises Hercule Poirot. Again, the links he puts in place don’t feel very much like Christie, but the tone of this is difficult to object to, and the eventual intention is well-managed. Good fun, as more stories should be.

We veer into spy territory with ‘The Man Who Read Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’ (1969), in which smalltown newspaper editor Terence Watson receives a seemingly innocent letter which nevertheless contains a cipher which will unlock some of the hostilities of the Cold War. The result is delightful, with tight phrasing (“He has a face as hard as a clenched fist.”), really entertaining ideas, and a solid reveal at its conclusion that made me laugh out loud.

I’m not sure where I got the idea that each story was a pastiche of the style of the author in the title, but the next two stories fully explode that: ‘The Man Who Read G. K. Chesterton’ (1973) explores similar ground to some of the Father Brown stories (c.f. ‘The Arrow of Heaven’ (1925) and another one I can’t remember) with its suicide in a locked top-storey office, but there’s none of the contradiction or subtle psychology that marked out Chesterton as something beyond the ordinary.

The sleuth is a Catholic priest, and so there’s the small matter of saving a soul by giving it a Christian burial, but there’s no interest displayed in the murderer in the way I had anticipated, nor, really, any reason to doubt suicide except out sleuth doesn’t want it to be. Interesting, too, is the use of pornography to justify the suicide, which provides the motive and a clue, but Gilbert would be appalled by such base activities, no doubt.

We come to a bibliomystery of sorts in ‘The Man Who Read Dashiell Hammett’ (1974), with a situation that every bookworm no doubt dreams of:

“Prichard, I” — the words came out reluctantly, “I need you…you seem to be the only one on our staff who reads detective fiction regularly…”

It falls to stack man Prichard to find a valuable book hidden in the library that will, if he’s successful, see the library bestowed with a hugely valuable collection. Hilarious that this makes reference to a Chestertonian principle, and I’m intrigued by the perception that detectives who live “just barely within the law and sometimes outside it” can only be found in hardboiled fiction, but let’s not get into that. This is a fun hunt, and one that the reader should thoroughly enjoy watching happen.

There’s a clever, Christie-level clue in ‘The Man Who Read Georges Simenon’ (1975), but Brittain isn’t structuring these in that way, it not being the style of the era, so we’re only told it after the detective — well, freight removal man — has realised it himself. Which is sort of a shame, because it’s brilliant, and deserves to be dropped on you to play the game as well. The Maigret-esque evaluation of character that the title implies doesn’t really come into effect here, either, so come to this as a fan of clever ideas rather than anything approaching whatever it was Simenon did (however I describe it won’t be right, so I’m just going to leave this here for you to interpret as you see fit).

‘The Girl Who Read John Creasey’ (1975) reminds me that I want to read some James Yaffe stories, this being framed around a hard-working cop who shares details of his latest case with his teenage daughter…only for her to stumble upon the key clue that unlocks a dying man’s final words. I really, really like this sort of story when it works well, and it works very well here, not least because Brittain is having so much fun with who “Ol’ Fishin'” could be — and it shows.

Part One concludes with ‘The Men Who Read Isaac Asimov’ (1978), a sort of Black Widowers pastiche in which four men who are fans of Asimov’s dining club stories form their own puzzle-solving club…and have, at last, their first case. In fairness, this isn’t a bad assumption of the Black Widower structure, with a local-boy-done-good offering a $1000 bill to anyone who can divine the combination to a safe he’s put in his shop window, and each of the men putting forth a solution informed by their own points of view.

But, lord, the Oirish speech of the tavern proprietor Findlay makes Randall Garrett’s Sean O’Lochlainn look like a nuanced and highly thoughtful portrayal of a denizen of the emerald isle. Might as well have shamrocks instead of speech marks and a man playing the fiddle and dancing a jig in the corner of the room whenever Findlay speaks. It is, you correctly surmise, rather distracting.

Given the clear division between the two parts of this collection, it seems sensible to compare the ‘X Who Read’ stories with themselves and so do a Top 5 at this point. To wit:

- ‘The Man Who Read John Dickson Carr’ (1965)

- ‘The Man Who Read Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’ (1969)

- ‘The Man Who Read Dashiell Hammett’ (1974)

- ‘The Girl Who Read John Creasey’ (1975)

- ‘The Man Who Read Georges Simenon’ (1975)

Certainly none of the stories are anything close to bad, and they remain highly, bewitchingly readable. Sure, I feel bad putting ‘…John Dickson Carr’ as the best, as if nothing else he did quite matched that debut, but the overall drop in standard really isn’t anything like as precipitous as it can be with other themed story collections, even more impressive when you consider that they represent nearly one-and-a-half decades of work.

I can understand editor Josh Pachter wanting to include the first Mr. Strang story to set up how a high school science teacher ends up involved in solving crimes, but ‘Mr. Strang Gives a Lecture’ (1967) isn’t especially strong. A student is accused of armed robbery, the prima facie evidence Strang uses to dismantle the case is pretty flimsy — one minute the kid’s an idiot, the next he’s not; the mileage could be easily faked — and apart from a few turns of phrase this is a pretty limp opening to Mr. Strang’s career.

A member of staff is accused on impropriety in ‘Mr Strang Performs an Experiment’ (1967), and I’m not sure Brittain really thought through how careful one must be when writing about this sort of topic. It’s overly superficial and problematic is so many ways, and I think I’m just going to pass right over it.

‘Mr Strang Takes a Field Trip’ (1968) sees a class of students involved in the baffling theft of a valuable artefact, with the two students who seem most likely to be guilty protesting their innocence. The solution is…fine, but I can’t get too excited about it. On this evidence, the ‘X Who Read’ stories are infinitely more interesting as contributions to the puzzle plot and crime writing in general, so it’s to be hoped that the criminous stories in Leonard Strang’s world take an upturn before too long.

A four-year gap here implies that editor Josh Pachter is not simply including the Strang stories chronologically, and is instead selecting the best ones lest there be no second collection (which we now know there was). So ‘Mr Strang Versus the Snowman’ (1972) raising standards somewhat is a relief. Concerning the distribution of drugs in the town — “[The teenagers] prefer [cocaine] to other hard drugs like heroin, because it doesn’t show up in urine tests, so they can take the school’s screening physicals without having to worry.” — Strang is roped in to find the suspected kingpin behind the distribution.

There’s a Chestertonian idea at the core of this, and a clever piece of action on behalf of our criminal that Strang is quick to unpick. As an updating of the classic puzzle plot to involve concerns more appropriate to the time of writing, this isn’t a bad example at all, and marks the first Strang case in this volume on a par with the better stories herein.

“I want you to explain the disappearance of Mr. James Phillimore Earnshaw,” is the challenge levelled by a city detective in ‘Mr Strang, Armchair Detective’ (1975). Heard arguing with his ex-wife after visiting her at her apartment, how could Mr. Earnshaw have vanished in the time it took two detectives to walk up the very stairs he should have been coming down? And why is there a knife in his wife’s living room and a fresh coat of red paint on her wall?

Now, see, this is more like it. The problem is neatly parsed, the workings are good, there’s one utterly superb clue, and the inference that you might assume is being made by Brittain to another famous case ends up being a part of the story in itself. And, best of all, the motive is also excellent. Wonderful stuff, should be far better known.

A junior school student is the artist when ‘Mr Strang Interprets a Picture’ (1981), but the story suffers because Brittain doesn’t quite have the light touch of, say, Edmund Crispin when it comes to the key clue being suitably presented. Sure, we don’t need to see the picture in question, but it would have been nice, and if you’re fooled by the name the young boy gives it, then, I’ve got some bridges you simply have to purchase.

Finally, ‘Mr Strang Takes a Tour’ (1983) in which someone joins a coach tour last minute at the same time as a robbery suspect is on the run. You’ll never guess what happens or who is responsible.

I’m not going to do a top five of the Strang stories herein, because, well, only two of them are any good, and if I continue to second volume The Man Who Solved Mysteries (2022) it makes sense to to a Top 5 of the Strangs in toto. I do have to wonder, though, that Pachter has selected these seven as, one presumes, among the best of the stories in that series, and that thought doesn’t exactly fill me with urgency to read further.

This volume is, however, more than worthwhile for the opening eleven tales, which show great versatility and imagination, carrying the puzzle plot into an era that would have received it less than enthusiastically. It takes real talent to write on the themes Brittain chose there, and so to do it as successfully as he managed is no small achievement. Here’s hoping that, should I get to them, the Strang remainders display more of that sort of quality — showing the playfulness, creativity, and general ebullience that betokens the upper echelon of this most frolicsome of genres.

I had the same problems you did with “Mr. Strang Performs an Experiment”. The basis of the entire plot – assuming that the accused teacher simply must be innocent – just feels so so wrong.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good review! I also really enjoyed this one.

“Mr. Strang Versus the Snowman” is one of my favorite short stories. It’s such a clear example of how logical deduction works; I’d honestly recommend it for anyone looking to learn to write mystery fiction.

I liked “Mr. Strang Takes a Trip” a little more than you did. Like you said, it’s not really fair-play, but I love both the central problem (Why would anyone steal a souvenir cross?) and how Strang deduces that the cross must have been stolen, not simply misplaced.

I suspect I’ll be getting the second collection in the future sometime.

LikeLike

This sounds like a very fun collection! I must have read this author because I’ve read the Mammoth Book of Locked Room Mysteries and Impossible Crimes, but sad to say I don’t remember it at all. Will have to put a pin in this.

That said, you mention James Yaffe- I’m a big booster of his Mom short stories. As a big anthology reader I of course faced the problem of having read what I think is the best one first (Mom Remembers) but the rest was still very fun. I have a special place in my heart for the collection (especially Mom Remembers) because I’m a New York Jew daughter and granddaughter and great-granddaughter of other New York Jews, and I feel like I don’t see enough of them in old-timey New York detective fiction despite how many of the writers were themselves Jewish. Mom Remembers is not only a very fun detective story in its own right, it also absolutely nailed its Jewishness in a way that I feel like I rarely see. Is the whole thing kind of “Thirteen-Problems-in-a-Bronx-apartment”? Sure, but nothing wrong with that.

LikeLike

As it happens, I recently started the Yaffe Mom collection, and I’m enjoying it so far. I’ve only read his story ‘The Problem of the Emperor’s Mushrooms’ before and was able to find a few flaws which allowed for alternative solutions, but I was always eager to read more. So anticipate a review in due course.

LikeLike

Yay, I definitely look forward to it! Glad you’re enjoying so far.

LikeLike