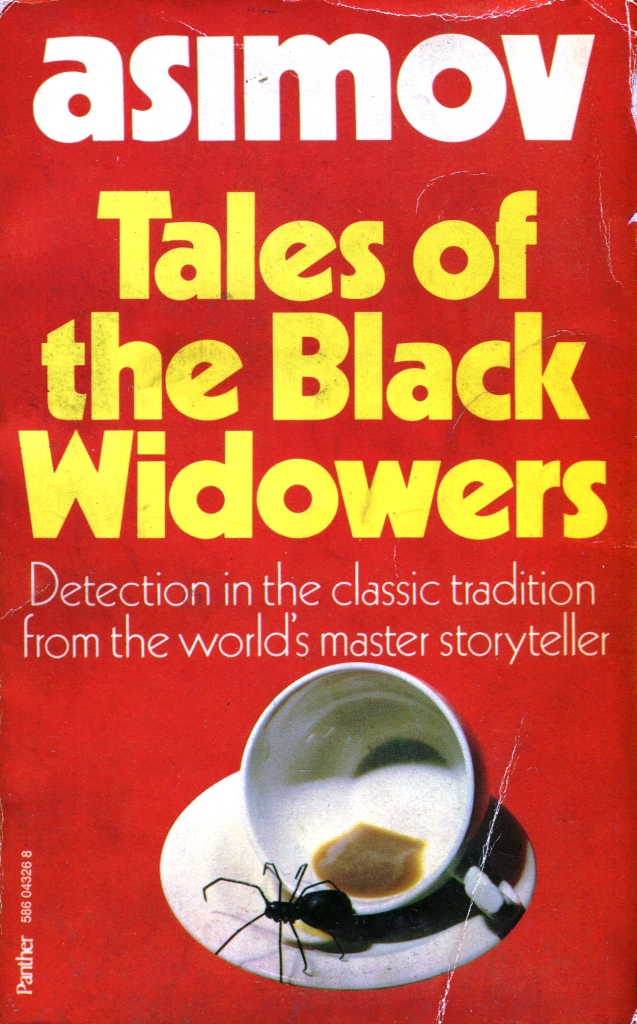

“Twelve mystery masterpieces by the maestro” promises the back cover of Tales of the Black Widowers (1974), the first collection featuring Isaac Asimov’s puzzle-solving dining club, and given that Asimov says in the introduction that his “detective ideal is Hercule Poirot and his little gray cells” it seems like it might not be an empty promise…

The Black Widowers, then, is a group of six men who meet monthly for dinner, one of the six (nearly) always bringing along a guest who will talk to the group on a subject of interest after the meal (frequently facing the opening question “How do you justify your existence?”). While waiter par excellence Henry dispatches brandy and cigarettes, the guest usually brings some problem before the club and is interrogated in return before a solution is provided. Asimov being the pro that he was, he peppers these discussions with little hints of verisimilitude which makes the whole thing feel less stilted than it otherwise might and fills out little character beats with beautiful touches.

Since the menu for that meeting had been so incautiously devised as to begin with artichokes, Rubin had launched into a dissertation on the preparation of the only proper sauce for it. Then, when Trumbull had said disgustedly that the only proper preparation for artichokes involved a large garbage can, Rubin said, “Sure, if you don’t have the right sauce…”

Nine of these 12 stories were originally published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, further enhancing their mystery credentials, so how do they stand up?

First, we have ‘The Acquisitive Chuckle’ (1972) in which private detective Hanley Bartram tells of two business partners — one a scrupulously honest man, the other an unprincipled louse and obsessive hoarder — who fell out and went their separate ways. One day, the latter came home to find the former in his house and, seeing his unexpected guest off the premises, became convinced that his nevertheless honest one-time friend had taken something from his house. The only problem? The house is “inordinately crowded with every variety of object and he didn’t remember all his possessions”. How, then, is Bartram to establish what has been taken?

The answer to this isn’t terribly surprising, but I was able to anticipate it mainly because of how well Asimov paints his characters, so that I had no difficulty believing in the setup and the resolution. How that answer is reached, however, was a source of great amusement, and the rigour with which the Black Widowers examine the scheme — bolstered, as Asimov points out in his afterword, by a point raised by a reader after the story’s publication in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine — does rather represent the rigour that the very best Golden Age stories had to offer.

It’s not the guest, but rather one of the Black Widowers themselves who raises the problem in ‘Ph as in Phony’, a.k.a. ‘The Phony Ph.D’ (1972). Refusing to believe that a mediocre student could have achieved an excellent grade on an exam that has famously proved exceptionally difficult for everyone who has ever sat it, and believing that the student’s consequent acceptance onto a Ph.D course cheapened the same achievement of anyone associated with the university in question, the story pours out.

There’s an ingenious false proposition in here, revolving around the notion that the exam honed in on mistakes made by the students during the course and so the students might have been faking a lack of understanding in the hope of influencing that topic’s appearance on the exam, but the eventual solution is a little tame, as perhaps befits this type of setup. It spoils nothing to say that the only real answer is foreknowledge, and it’s simply a matter of which way Asimov jumps to provide that. I don’t mind the answer, but it’s not as insightful as the solution to this story’s progenitor.

In ‘Truth to Tell’, a.k.a. ‘The Man Who Never Told a Lie’ (1972), John Sand comes before the Widowers accused of a theft that only he could have perpetrated, that of “a sum of money and a wad of negotiable bonds” which have been taken from a safe at the company where Sands’ uncle employs him. Since his reputation is on the line, Sands throws himself before the Widowers in the hope of some explanation to the disappearance, made all the more intriguing because he was the only one who knew the safe’s combination and had the means to remove the items in the allotted period.

This…doesn’t work. The imperative of the Widowers to come up with a solution without involving anyone external to the meal — part of the agreement is that everything said while at the meetings is confidential — is an interesting moral problem, and Asimov is having great fun trying to tell the story of the Iliad in limerick form, but the solution is, if you want to engage in strict formal logic, not as clever as it thinks. It’s also odd that…well, the story contains a trope that I’m not sure it’s safe to discuss without spoilers (rot13: gur pevzvany orvat gur bar jub oevatf gur qrgrpgvir va ba gur pnfr) and in this short form it makes even less sense.

Far more successful is ‘Go, Little Book!’, a.k.a. ‘The Matchbook Collector’ (1972), which — with more joyful limericking, this time involving the Odyssey — raises the possibility of an uncrackable code when it’s virtually known that a man is communicating something in coded form to interested parties…but precisely what and how is unknown, despite some very clever minds wrangling with the problem.

“Any system for transmitting information that can’t be broken — whatever the information is — is top-flight dangerous. If it works and is being used for something utterly unimportant, it can be later used to deal with something vital. The government doesn’t want any system of transmitting information to remain unbroken, unless it’s under its own control. That’s got to make sense to you.”

Not only is the idea clever, the notion of bemoaning the supposed brilliance of amateur sleuths (“You know ever since Conan Doyle pitted Sherlock Holmes against the Scotland Yard bunglers, there seems to be a notion going around that the professional can’t do anything.”) in a series of stories which are turning out to be about a brilliant amateur sleuth is…just delightful.

I’m not sure quite what to make of ‘Early Sunday Morning’. a.k.a. ‘The Biological Clock’ (1973). On one hand, it’s a clear step into the more personal nature of crime writing that would have predominated its era, concerning as it does not an abstruse, minor problem presented by an outsider but instead the murder of the sister of one of the Widowers a few years previously. The tone is commensurately more sombre, as the questions asked are treading on ground that is undeniably painful for one of the group and so things progress in a way that is at once familiar and different.

And yet, for all this bending to the conventions of genre expectation, the trick at its core is…rather brilliant. I read this a couple of weeks ago and I still find myself vacillating between “Nah, that would never happen…” and “Actually, yeah, I can see how they might…”. The key thing is that Asimov lays the necessaries for this explanation — the who isn’t a surprise, it’s more the how — with the deftness of the genre’s masters, so that you’ll happily overlook the obvious explanation because of the subtlety with which he folds the clewing in. That’s no small feat, and as such deserves more than a little respect.

Bringing up the halfway point of the collection, and presenting perhaps the most fascinating possibility in the collection, ‘The Obvious Factor’ (1973) concerns an idea from which much hay has been made both in crime fiction and SF: the small matter of precognition. Here, it’s a case of a shop worker who graduates from being able to spot shoplifters with 100% accuracy to predicting a fire some 3,000 miles away mere moments before it happens and so comes to the attention of Dr. Voss Eldridge, Associate Professor of Abnormal Psychology.

Again, the interrogation of possibilities to explain this is as impressively rigorous as always — though I realise now that the individual Widowers stand out to me not one bit, and the setup would have been more effective if a single, Old Man in the Corner-style sleuth were utilised — but the solution…well. I’ll repeat my usual refrain that if you want to read a rationally-explained crime story about prophecy then you should read ‘The Cleaver’ by Paul Halter because it’s a masterpiece which nothing else I’ve yet encountered comes close to rivalling. Asimov’s effort is fun, not least for his repurposing of the famous Sherlock Holmes aphorism in the endnote, but best neglected.

Another classic trope with a dying message in ‘The Pointing Finger’ (1973), in which a dying man keen to tell his heirs of the location of their inheritance indicates the Complete Works of Shakespeare before shuffling off this mortal coil. Asimov is once again enjoying himself immensely, not just with his dissection of the Dying Message as a trope…

“In mystery stories the dying hint is a common device, but I have never been able to take it seriously. A dying man, anxious to give last-minute information, is always pictured as presenting the most complex hints. His dying brain, with two minutes’ grace, works out a pattern that would puzzle a healthy brain with hours to think. In this particular case, we have an old man dying of a paralyzing stroke who is supposed to have quickly invented a clue that a group of intelligent men have failed to work out; and with one of them having worked at it for two months. I can only conclude there is no such clue.”

…but also in the revelation of himself as a friend of one of the Widowers and a frank egoist at that. What I dislike about this story is that the solution shouldn’t be possible because that eventuality was dismissed in a single line early on (rot13: ‘Jr’ir frnepurq rireljurer!’), and as such the clever interpretation put on the dying message shouldn’t stand. But it does, because Asimov likes the — as a say, clever — idea he had here and so we throw over something that shold have been dealt with and provide a solution that is, to my way of thinking, completely unfair.

‘Miss What?’, a.k.a. ‘A Warning to Miss Earth’ (1973) serves as an excellent reminder — unostentatiously, of course, he’s too classy to brag — of what a superb scholar Asimov was, not least in his exploration of the Old (1967) and New Testaments (1969). When a police lieutenant brings to one meeting a note which apparently threatens a contestant in the Miss Earth competition taking part in the city, its couching in apparently biblical terms gives the Widowers much to chew over, and shows Asimov in full creative flight.

My difficulty with the solution is that there’s no reason for it to be ‘correct’ any more than many of the other possibilities discussed can be called ‘wrong’ on balance of sheer probability alone (“Why does the writer have to be Jewish? Most Fundamentalists are Protestants…”). As an exercise on how to spin only the barest amount of straw into gold this is a textbook piece of plotting genius and should be studied by anyone interested in the rigour of proper detective fiction, but as a mystery story it falls someway short of the standards it works so hard to uphold.

Three stories written especially for this collection follow, and I have to wonder whether they would have been published by EQMM even with Asimov’s name attached. ‘The Lullaby of Broadway’ (1974) takes an interesting idea — the witnessing from the outside of some possibly innocent activity that has a deeper, more sinister interpretation — and fumbles it because of the conventions of the armchair detection direction these stories have taken. And while ‘Yankee Doodle Went to Town’ (1974) at least acknowledges the rigorous, unspeculative nature of of mathematics, it’s a spurious wisp of an idea based on unconscious association relying on startlingly obscure knowledge and some deeply faulty reasoning. And ‘The Curious Omission’ (1974), while hinging on a piece of wordplay that is fitting for it’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) framing, is on of those false-feeling puzzles where the setter has twisted himself in knots to make the setup conform with the answer.

The received wisdom with short story collections is, though, to Finish On A Strong One, and ‘Out of Sight’, a.k.a. ‘The Six Suspects’ (1973) is one of the better efforts in this collection. Highlighting how good Asimov is at McGuffining, it doesn’t matter what the suddenly-classified contents of Waldemar Long’s cancelled speech were, just that only one of the six other people at his dinner table could have heard him complaining about its suddenly-classified nature and so have crept out — or arranged a distraction while their partner crept out — and hurried to Longs room to photograph the contents.

The central idea here is nothing new, supplying as it does the core oversight in two underwhelming Agatha Christie novels and countless not-as-clever-as-they-think short stories, but it’s such an old chestnut that you sort of feel a misty-eyed fondness for it being trotted out in the 1970s, all spick and span and dressed in its shiny new clothes. And the nature of how the solution is reached feels more realistic to the universe, too, and as such doesn’t give the impression, as the weakest stories here do, of the reader being forced into a narrative headlock and made to look only in one direction at what the author insists is the only possible solution. So, yes, a good choice to finish on.

~

So, twelves mystery masterpieces by the maestro? Hmm, perhaps not — some nice ideas, and some clever framing of slightly disappointing ideas, but not really what you’d call a masterpiece among them. One really feels Asimov stretching his toes here, enjoying the freedom of being able to bring his undeniably vast intellect to a more playful story form, but were this the first I’d ever heard of the man an his work — perish the thought! — I can’t say I’d rush back with any avidity. These are light, fun, and good for a well-written distraction, but it’s understandable why he made his name in SF even if he does show some flashes of ingenuity on this side of the fence.

My top five from this collection? Well, since you asked…

- ‘Go, Little Book’, a.k.a. ‘The Matchbook Collector (1972)

- ‘Early Sunday Morning’. a.k.a. ‘The Biological Clock’ (1973)

- ‘The Acquisitive Chuckle’ (1972)

- ‘Out of Sight’, a.k.a. ‘The Six Suspects’ (1973)

- ‘Miss What?’, a.k.a. ‘A Warning to Miss Earth’ (1973)

I have no more of the Black Widowers collections, but will doubtless stumble over them in time and will certainly look forward to more of Asimov’s brand of slightly-disappointing-but-very-enjoyable mystery. Any highlights ahead I should get excited about?

Yeah, I haven’t met a single person who actively reads mysteries that has read this collection and walked away enthused about it despite its apparent esteem and reputation. I believe TomCat shares your general lukewarm feelings for this collection, and my friend “Life” also didn’t care for it either… It seems like Asimov’s best mysteries will always be his science-fiction ones.

LikeLike

The lies, the horrors, I love the Black Widowers series, and especially this collection, but as TomCat says it’s probably more for the characters rather than the actual puzzle plots themselves.

LikeLike

Watch this space for more Black Widowers, because I’m intrigued enough by the very good stronger end of these tales to investigate further. And, as I’ve said elsewhere, I can easily believe that each collection, while variable in quality, will have some genuine class in it somewhere.

LikeLike

I’m such an Asimov fan that I’ll find the merit in practically everything he wrote, so it’s a shame to come away from these feeling underwhelmed. But at least I’m not alone! And I did enjoy the framing of each tale — Asimov is great at the setups, rather than just plunging straight into the story. So the manner of their telling will keep me reading, even the contents don’t quite fly.

LikeLike

I have read all but “The Return of the Black Widowers” and definitely didn’t read this first collection first so I was never happy with the first story as to me it felt unusually cruel. The one that sticks in my mind most because it touches upon another of my interests is I think “Nothing Like Murder” from “More Tales of the Black Widowers”.

LikeLike

I can easily believe that each collection contains some strong highlights — and that a Best of the Black Widowers collection would be very good indeed.

As to ‘The Acquisitive Chuckle’ being cruel, I enjoyed the conceit, especially as it gives characters I’d come to believe in a chance at some revenge. Cruel perhaps, but then don’t we read stories of murder and blackmail for fun? 🙂

LikeLike

I suspect a plate of artichokes would make it a fairly short meeting!

LikeLike

😄

LikeLike

This is one of those series I like more for the characters than the plots as their banter and discussions often are more interesting and amusing than whatever problem their guest brings to the table. Not that the plots are all necessarily bad. Just that a lot of them tend to be slight and forgettable like that one story in which the guest asks the Widowers to help find a woman he spotted on the bus. On the other hand, the variety of problems brought to their dinning table can really only be found in this series (or Q.E.D.). It has everything from code crackers and impossible problems to some puzzles that are not easy to categorize. For example, “The Ultimate Crime” from More Tales of the Black Widowers has the Black Widowers helping out a Baker Street Irregular writing an article on Professor Moriarity’s book, The Dynamics of an Asteroid. So a fun series with some creative and unusual stories, but definitely limited as pure detective stories and therefore not everyone around these parts are going to warm to them.

LikeLike

You make me suspect that, now I have a better understanding of their nature, I might actually get more out of future collections — always provided I can track them down, of course.

And banter of this nature is very hard to capture well, so Asimov deserves credit for making something that should be easily dismissible into an engaging and appealing part of his milieu.

So, huh, maybe there’s more to be positive about here than I initially suspected…

LikeLike

I recommend hunting down a copy of The Return of the Black Widowers. A fitting, final collection gathering the stories that were left uncollected, a best-of selection, two pastiches (William Brittain’s “The Men Who Read Isaac Asimov” and Charles Ardai’s “The Last Story”) and a crossover story (“The Woman in the Bar”) with Darius Just from Asimov’s Murder at the ABA. Which also makes it a perfect introduction for readers who are (relatively) new to the series.

LikeLike

I read all the Black Widowers collections that our library had back in the 80s and loved them. I think I liked the set-up–discussing problems over dinner and Henry being clever at the end of so many of them. I reread the Casebook collection in 2017 and found it pleasant and fun, but not heavy in the mystery department.

LikeLike

I’ve just looked up how many collections there are, and see it’s surprisingly more than I thought:

More Tales of the Black Widowers (1976)

Casebook of the Black Widowers (1980)

Banquets of the Black Widowers (1984)

Puzzles of the Black Widowers (1990)

The Return of the Black Widowers (2003)

So clearly Asimov enjoyed writing these. I’m assuming that it makes no difference which order these are read in, right? The chances of my stumbling over More Tales next seems pretty slim, given that I’ve only ever seen this first collection once in all my secondhand bookshop trawling.

LikeLike

Glad to see you reviewing the Black Widowers. They are right up my alley with their intellectual settings and stronger focus on plot than characterisation (the Widowers themselves are more archetypes than actual characters in my eyes).

I don’t think the stories need be read in a particular order, though I have some kidn of niggling feeling in the back of my mind that there might be something in the last collection that relies on knowing something from earlier – though it might simply be because the last volume not only collects the final stray stories by Asimov but also a continuation story by Charles Ardai.

LikeLike

Good to know, thanks. I look forward – eventually — to many more hours in their company.

LikeLike

All of the Black Widowers books are available for free on the Internet Archive. Thanks for reminding me about them, I binged my way through them around 30 years ago and haven’t thought of them since.

LikeLike

Ah, good to know. One of these days I really must work out how the Internet Archive works…

LikeLike

Just go to the URL https://archive.org/search?query=black%20widowers (which is a search for the black widowers books) and click on the book you want to read. Then “check it out” like a library.

LikeLike

Ha, amazing; many thanks!

LikeLike

I tried to post this comment a couple of times, but it kept disappearing into the void of the internet. So let’s try it one more time:

I recommend tracking down a copy of The Return of the Black Widowers. A fitting, final collection gathering the stories that were left uncollected, a best-of selection, two pastiches (William Brittain’s “The Men Who Read Isaac Asimov” and Charles Ardai’s “The Last Story”) and a crossover story (“The Woman in the Bar”) with Darius Just from Asimov’s Murder at the ABA. Which also makes it a perfect introduction for readers who are (relatively) new to the series.

LikeLike