Another exclusive boarding school, another murderer on the loose — if mysteries for younger readers are anything to go by, put your kids in the local comp to keep them safe.

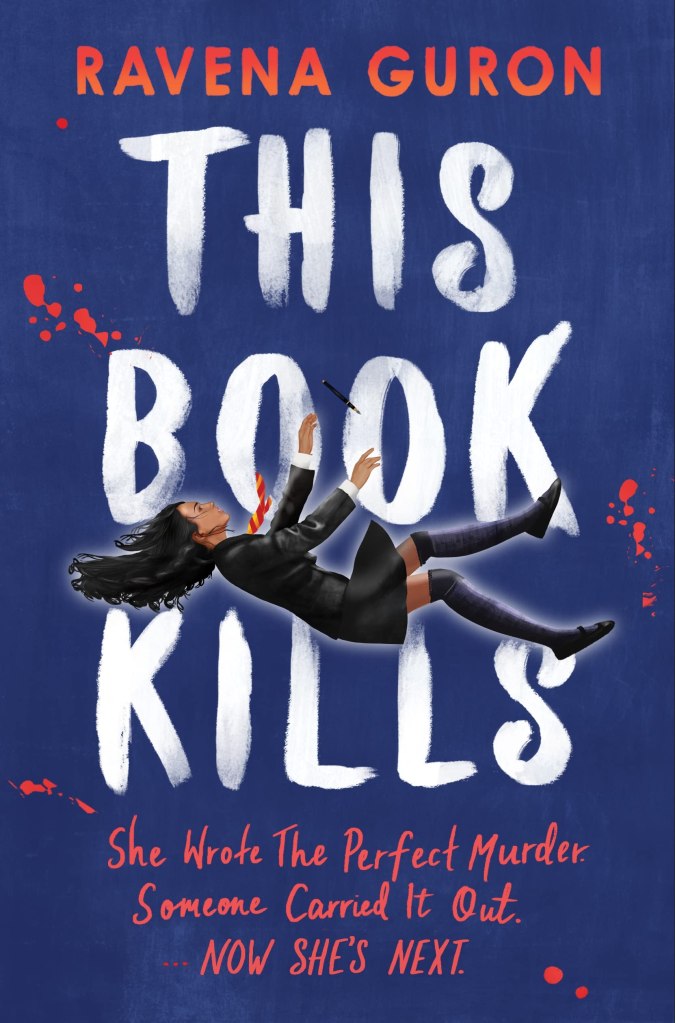

Judging a book by its cover is discouraged, but sometimes unavoidable, and This Book Kills (2023) by Ravena Guron falls prey to in a way that would be unfair, but equally unavoidable, when measuring it against your expectations. She plotted the perfect murder, it promises, implying that the murder story Jesminder ‘Jess’ Choudhary writes with another student has some element of cleverness to it which made it deeply appealing to the school’s resident psychopath, as per short story ‘The Blind Spot’ (1945) by Barry Perowne. Alas, the method is fairly prosaic — the small matter of being hit over the head with a prize cup taken from the school’s vast trophy cabinet — so if you’re coming to this for its ingenious murder premise (and, if you are, perhaps seek help) you’ll leave a little deflated. But I’d suggest sticking around, because Guron’s book has much to recommend it, not least a murder scheme which slipped one of the classic pieces of misdirection past me on the way to explaining the various violent happenings in its very entertaining pages.

When school hunk Hugh Henry Van Boren is found in the woods surrounding Heybuckle School with some of his insides on the outside and a bloody football trophy on the ground next to him, near twigs arranged into the words HELP ME, the school is shocked. But no-one is as shocked as Jess and writing partner Summer Johnson, the two girls having been paired for an assignment in which they described the violent end of a man in that exact manner. And when Jess starts receiving texts from someone claiming to be the killer, thanking her for the inspiration and threatening to kill her next unless she confesses “what you did last year”, it becomes apparent that all is not well and no-one is safe.

Someone in school — perhaps someone I saw every day — a teacher, even, or a student, had killed Hugh. And the idea they were walking around school, blending in like nothing had happened, was terrifying.

Guron’s style is easy to read, and her setting neatly drawn without ever feeling overwhelming — no mean feat given the implied size of the cast at play. The sense of paranoia she engenders boils just below the surface, with grief, shock, fear, and the desire to blame someone all key factors in the behaviour of the various elite teenagers who populate the school, and Jess’ status as an outsider — she is one of the dwindling number of students granted a scholarship to attend Heybuckle, coming as she does from a disadvantaged family — sets her up perfectly as both object of derision and the only Outsider who can really investigate things (after all, the best detectives are Outsiders and I’ll hear no talk otherwise). Indeed, Guron mines Jess’ Outsider nature well, with both a sharp pathos…

I didn’t want Miss Evans, our house-mother, to find out about this — I didn’t want any adult to know. I was too embarrassed. Because it felt like there was something shameful about being bullied like this, because I was already the different kid, the scholarship kid, the poor kid — the Indian kid.

…and a wryness that befits a seventeen year-old, such as Jess’ reflection that she and Lucy Huang are always picked to appear in photos for the school’s prospectus (“If I had a penny for every time I’d actually sat on the sweeping lawns of Heybuckle School chatting with my group of diverse friends, I’d be about as rich as I am now.”). As narrators go, she’s very likeable, with a twist of steel to her makeup (“I was never ashamed of where I came from. I never pretended to be anything other than a scholarship student from a poor area of London.”) that rings all the more true when she begins to investigate the murder, not trusting the police or the private investigator employed by the dead boy’s parents to unmask the killer before they arrange a trophy-based introduction ‘twixt Jess and her maker.

And Guron’s skill extends beyond simply her main character, limning Heybuckle, its denizens, and the lofty separation of the rich with a minimum of light touches and throwing in some superb descriptions along the way:

Inspector Foster was nearly six foot, with a fringe of brown hair that fell into her eyes, the sort of hairstyle I had when I was five. Her thin lips seemed to fall naturally down into a frown, like gravity was working extra hard on them.

She also deftly works in several key themes that might have the narrow-minded rolling their eyes, but are undeniably hugely important to face — and face intelligently, as this book does — for its target audience. Hugh is, objectively, a fairly terrible person, having been cheating on his girlfriend for several months with Jess’ best friend Clem and having as his closest friends other priggish, entitled pillocks. And yet Clem tells Jess of the sweeter, more caring side Hugh could present at times, and how in many ways he was a very understanding young man probably just trying to make sense of a world that’s pretty confusing when you’re that age. Indeed, the idea that someone can present two apparent irreconcilable faces to the world is written through the whole narrative, not least because one of the characters we get to spend a lot of time with ends up revealed as a murderer in the closing pages.

Elsewhere, Guron examines ideas around guilt and culpability, around the treatment of young women and the perception of their place in society (and even that’s given more consideration than you might suspect)…it’s heavy stuff, but done so lightly as to give genuine thought to an issue without ever dragging you down into Issue-Of-The-Week Fiction. Hell, if you just want to read this as a fast-paced Killer On Campus thriller you can, but Guron deserves a huge amount of credit for writing a book that does more than just entertain, and addresses difficult ideas intelligently and with genuine deftness. It’s not perfect — on at least two occasions someone “hisses” a sentence without a single sibilant anywhere in its structure (“You’ve got no idea what you’re doing.”/”What did you call me?”), but, well, you can’t have everything.

And the mystery is pretty good, too — not clewed in the traditional sense, but relying, as I said above, on a classic piece of misdirection that really does play into the notion of “[a] single puzzle piece, that doesn’t make sense on its own. But when you put it all together…then you see the full picture”. I figured out about half of the answer, because I’m practically genetically modified to think in a certain way after decades spent reading this type of fiction, but a failure to properly interrogate what that conclusion meant resulted in me missing the bigger misdirect…and I’m fine with that, because it’s always lovely to get to the end of a mystery and be surprised. And surprised I was, and lovely it most definitely felt.

It is to be hoped, then, that this is not the last we see of Ravena Guron in the mystery sphere. She has a good eye for detail, a keen sense of pacing, a well-judged feeling for clear plotting that obscures astutely, and a real talent for writing smoothly about ideas which scream out to be uncomfortably wedged in with jagged edges. In short, This Book Kills is a triumph, and I look forward eagerly to whatever follows.