I shall eventually abandon any pretence that my occasional forays into post-1990 impossible crime novels are purely for the benefit of my fellow impossible crime enthusiast TomCat, but not just yet. So let’s all take a moment to bask in how selfless I am, reading books I have no interest in myself purely so that TC can find something more modern to satisfy the cravings of the Impossible Murder Phanatic (or ‘Imp’, as those people have definitely been calling themselves for years now).

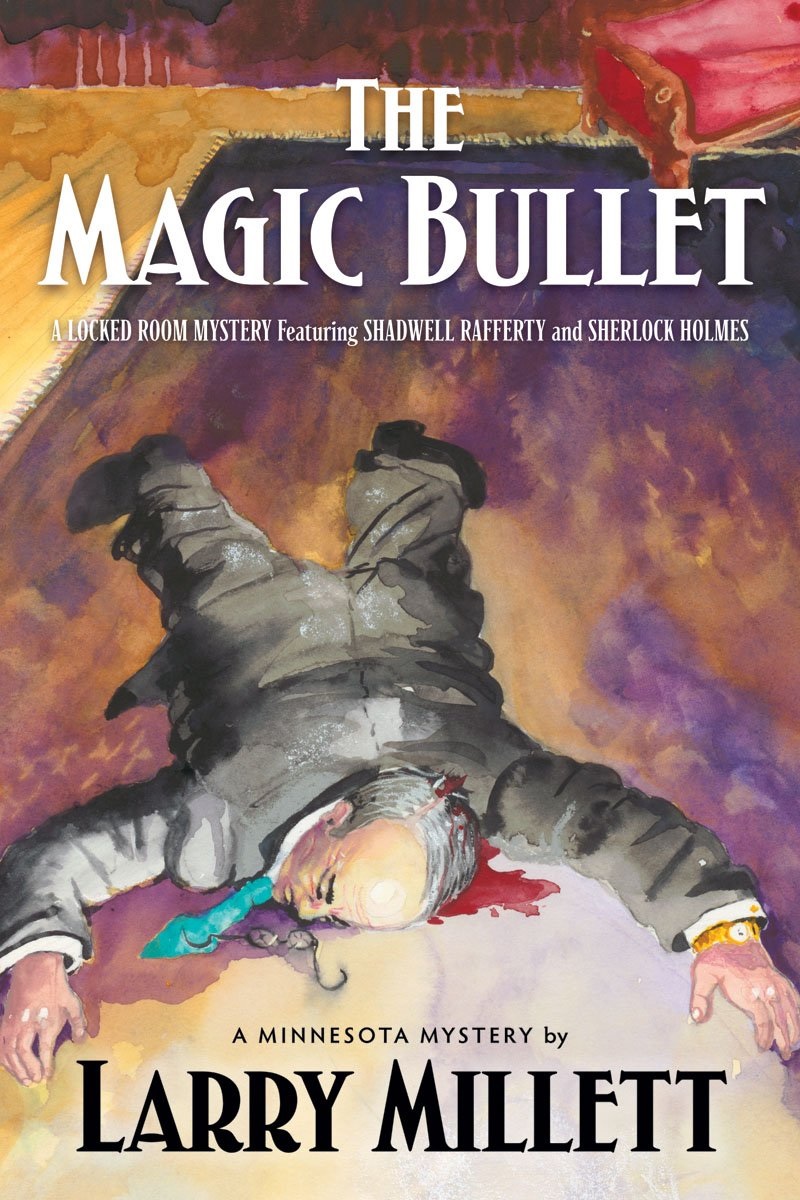

So, here’s one of my reading foibles: when I start a new book, I typically like to read at least the first 10% of it in one sitting. I’ve no idea where this has come from, and I’m not exactly obsessive about it, but it happens significantly more often than not. The Magic Bullet (2011) is 344 pages long and so I needed to get to page 34, which is pretty achievable for a man of my age and attention span…and I made it only as far as page 8 before having to put it down.

It was specifically this paragraph which broke me:

Rafferty tipped his hat, earning a small nod from the woman, just as Police Chief Michael Nelligan walked into the lobby from a connecting hallway. He was a tall, slender man, and he might have been handsome except for a certain sourness to his features. Around the police department he was known as “the big pickle,” and it wasn’t a compliment. Nelligan had replace the legendary John J. O’Connor as chief only a month earlier, and he was eager to make his mark. He had a reputation as a skilled bureaucrat, canny politician, and stern administrator. The chief was also known to be a skirt chaser who pursued and even occasionally hired beautiful women for a night’s entertainment. Rafferty knew Nelligan just well enough to dislike him.

Now, put Millett’s laudable use of the Oxford Comma aside for a moment and instead reflect on just how much Tell and how little Show is evident in that writing. And this is the eighth page — of a hardback book, incidentally, so it’s 8 big pages of fairly small font — of this sort of writing. Millett front-loads every character and introduction with biographical detail in this manner as if worried that he’ll forget to work it in later…and this periphrasis could be vaguely justified if any of it were to be relevant at some later point. Nelligan’s a skirt chaser, you say, and known for hiring prostitutes? He and Rafferty dislike each other? Can’t wait for those facts to play some part in the narrative. Oh, not so much. Maybe it’s a setup for the sequel…?

To top it all off, our septuagenarian sleuth Shadwell Rafferty — sometime barkeep and confidante of Sherlock Holmes, making the 1917 setting jar with the accepted Holmes canon — isn’t especially likeable. During the chapter in which he and his Watson stand-in George Washington ‘Wash’ Thomas are walked through the murder of financier Artemus Dodge in his super-secure office-cum-apartment in a skyscraper’s penthouse, Rafferty misses no fewer than three opportunities to make a comment along the lines of “Well, he wasn’t as safe in there as he thought, eh?” — yeah, okay, dickhead, we get it. Equally, his guide on this murder tour is the security guard Peter Kretch, whom Rafferty rebukes for calling him ‘sir’ because “Rafferty knew that politeness was often aggression in disguise”. And yet when literally any other character shows politeness to Rafferty for the rest of the book — an elevator operator calls him ‘sir’ a few pages later — it’s seen as the natural order of things and Rafferty accepts it without comment.

Suffice to say, things were not off to a good start.

The murder of Artemus Dodge, however, is intriguingly framed: the office in which the murder takes place is set back from the outer wall of the building and screened from view by metal bars some two inches apart, and of the two doors giving entry to the victim one would require “some serious drilling or explosives to open it” and the other is possessed of an interesting security feature which renders it impossible to close once opened. And yet here we are, with out influential money man shot in the back of the head, no gun in the room, and no way for anyone to have gained entry, nor to’ve left once that second door was opened (in full view of several independent witnesses).

Floorplan!

In the teeth of such a classical impossible crime setup, Millett also peppers his novel with references to the works of sometime fictional impossible crime dabbler John Dickson Carr. These range from the obvious (characters called J.D. Carr, Hank Merrivale, and a “slimy lawyer” Patrick Butler) to the standard (“Even more intriguing was an essay written by a certain Dr. Gideon Fell that described the various kinds of locked room mysteries and how to solve them”) to the pleasingly subtle (“There is no need here,” Rafferty is told at one point, “for men who explain miracles”, or one character being described as “a schemer in dark corners” best through of as “he who whispers”). In his author’s note at the end of the narrative, Millett acknowledges Carr as a “prolific writer best known for his atmospheric locked room mysteries, which by virtue of the intricacy, inventiveness, and variety have no equal in the literature”. Millett also goes on to cite particular titles, including one which “inspired certain features of my own humble attempt at a locked room mystery”.

Now.

‘Inspired’ is a big word. It’s up there with ‘suggested’ — as TomCat so recently brought to our attention — as a way of lampshading all manner of infelicities with regard to such authorly undertakings as, y’know, “coming up with your own plot” or “coming up with your own solution to an impossible crime”. ‘Inspired’ here feels…baggy enough to allow for all manner of implications, which can be taken either way. Someone upon reading this book might — might, I remind you, as I’d hesitate to make any claims with certainty or legally-punishable claims behind them — one again might see the solution here as a complete steal in virtually every regard. However, thankfully that’s not even the book’s biggest problem, so let’s move on.

The book’s biggest problem is that the solution as suggested by Shadwell Rafferty in the penultimate chapter does not work. Indeed, because it was in the penultimate chapter I had visions of a Roger Sheringham-esque sneak-twist reversal in the closing pages: of a narrative that had deliberately set us up, spoon-fed us Carr references, and stolen a Carr solution so that we’d be at peak outrage…only for the rug to be swept gloriously from beneath us with a knowing and devastating reversal. This would, in its own way, be a Carr homage of quite staggering brilliance, and forgive most of the adventure-focused foregoing and the complete and total disregard for fair play, any interest in detection, and that weird front-loading writing style that even sees Rafferty sit down to read biographies of the suspects in the case — complete with blunt physical descriptions, in case you didn’t tune into the first episode last week — at one stage.

Alas, no. The floorplan shown above is sent to Holmes and Watson “in our flat at 221B Baker Street” — though I’m pretty sure that 1917 is long after Doyle had retired Holmes to the countryside to tend to his bees — and from it Holmes apparently intuits the solution to the crime, and since we’re given no such reversal as anticipated (neither, in fairness, are we told Holmes’ solution) we must assume that the floorplan is accurate and Rafferty’s solution is Holmes’ solution and therefore both men are correct. But once you know the solution, looking at the floorplan shows that it doesn’t work. I’ll simply say that…stuff is in the wrong place. This is no It Walks by Night (1930) moment where you look over the floorplan and smack yourself in the face for your stupidity; it’s more like…uhm, I dunno, something very stupid that’s supposed to provide clarity and yet in reality occludes what it claims to be illuminating. If the solution to this crime is a cake, the floorplan is a 3 year-old in the kitchen ‘helping’ you make it.

And — jeepers and, the bad news isn’t over yet — the summation Rafferty gives at the end, featuring all manner of “well I imagine that this happened…” and “we must assume that…”, doesn’t even match the commission of the crime as told to us at the very start of the book. Which might not seems like the most pressing problem, given how much plausible deniability Rafferty works into his version of events, but it does sort of undercut the brilliance of your detective when he’s telling you what happened and you, the reader, know for a fact that it’s not what happened (in part, see, this was the germ of my hopes for a Sheringham-esque reversal). And it’s especially baffling when there’s no real need for there to be a disparity, either: you could simply not include the opening couple of pages detailing the murder and everything would sort itself out. It’s almost as if that opening description was forced into the book with Millett under some sort of duress, and in his reluctance he didn’t want to spend too much time thinking about it…except that it’s followed by 340-odd pages of Millett front-loading all his descriptions and events. So it’s more likely he wrote it, and then didn’t really care that it didn’t need to be there.

Floorplan!

It is much more successful (and that may seem like a back-handed compliment at this stage) as a piece of historical fiction, which you suspect is where Millett’s interest really lies. And the shame of it is that had Millett reversed the proportions of these aspects of his novel — making the history more of the focus and throwing in the impossible crime as an aside or part of the bigger plot, rather than making it the focus on page 1 and so everything that follows must feed into it — this would be a far better novel. The historical elements are rich and finely-realised, almost to the extent to trying to become the focus by the halfway stage, and thus leaving you with a novel that won’t pick a lane. Chop about 40 pages of history out, and it would be a more sensibly mixed brew, with history as a backdrop to sensation. Alternatively, chop about 50% of the impossible crime out (and, y’know, give it a solution that actually works…) and it would be a strong historical jaunt with echoes of classical impossibility in the vein of Carrs own The Devil in Velvet (1951), or a less compellingly framed The Bride of Newgate (1950). As someone who clearly has such an interest in history, Millett deserves an editor who is able to emphasise this aspect of what he writes, or one who is able to spot when true location of Millett’s heart betrays itself in crowding out the novel of…er, crime (I can’t in all good conscience call it detection) he’s writing so as to lure people into his history lesson.

I’m going to level with you: I didn’t really like this book. It’s one thing to claim some sort of enigmatic mentorship on behalf of the touchstone name in the field and then essentially rip him off, but it’s another thing entirely to do it so cack-handedly, with evidence not supporting your conclusions, characters behaving inconsistently because the initial intent is for them to appear more interesting only for this to remain unaddressed, unresolved, and unreferenced for the remainder of the book, and with a patchwork narrative that wants to give everyone Something Mysterious as a Massive Red Herring and so ends up obviating all reason and serving up a mish-mash of taradiddle and speculation the like of which it is rather difficult to fathom out as an experience in plotting, detection, impossible crimes, pastiche, homage, Sherlockiana, historical fiction, and/or any of the other facets in which this miserably falls down flat. If you want to learn about St. Paul, MN in the early 20th century, however, go for it: skip out all the bits in Part One where people are talking — actually, just skip the first section altogether — and you’re in (ahem) heaven.

Alas, I am not here for the history in such unpalatable chunks, and I like the criminous enterprises I engage with on the page to possess at least a modicum of internal logic. And it’s especially disappointing as I was hoping for some half-decent Holmes pastichery to tide me over until Anthony Horowitz comes through with another of his own takes on the character and universe, and Millett has written some five or six of these that might have filled the gap nicely. Man, even David Stuart Davies is looking desirable after this effort…

~

Finding a Modern Locked Room Mystery ‘for TomCat’ attempts:

The Botanist (2022) by M.W. Craven

Hard Tack (1991) by Barbara D’Amato

The Darker Arts (2019) by Oscar de Muriel

Mr. Monk is Cleaned Out (2010) by Lee Goldberg

Death on the Lusitania (2024) by R.L. Graham

The Dog Sitter Detective Plays Dead (2025) by Antony Johnston

Impolitic Corpses (2019) by Paul Johnston

The Secrets of Gaslight Lane (2016) by M.R.C. Kasasian

Murder at Black Oaks (2022) by Phillip Margolin

Murder by Candlelight (2024) by Faith Martin

Murder Most Haunted (2025) by Emma Mason

Angel Killer (2014) by Andrew Mayne

The Magic Bullet (2011) by Larry Millett

The Murder at World’s End (2025) by Ross Montgomery

Black Lake Manor (2022) by Guy Morpuss

The Direction of Murder (2020) by John Nightingale

Holmes, Margaret and Poe (2024) by James Patterson and Brian Sitts

The Paris Librarian (2016) by Mark Pryor

Lost in Time (2022) by A.G. Riddle

The Real-Town Murders (2017) by Adam Roberts

By the Pricking of Her Thumb (2018) by Adam Roberts

Murder in the Oval Office (1989) by Elliott Roosevelt

Murder at the Castle (2021) by David Safier [trans. Jamie Bulloch 2024]

With a Vengeance (2025) by Riley Sager

Red Snow (2010) by Michael Slade

Ghost of the Bamboo Road (2019) by Susan Spann

I stumbled upon this I think during the Winter, but its price was so ridiculous (over 20 euros) price that i evaded it. I guess you could say I evaded this one & hope you bought a used copy!

Btw, I’ve finished the first two by Innes. I don’t really see any magic yet, but the killers are so obvious in both that I think that TomCat will have no problem starting from Ripples and going back.

LikeLike

I didn’t buy a used copy, but I didn’t pay €20 for it either. I found it new for a good price, having been umming and aahing over it for a while, and so it thankfully wasn’t too ridiculous a financial risk. The biggest shame is how no-one has cast an editorial eye over it, because had it bee given even a cursory read it would be clear that there are problems with the central murder, and that the mix of history and detection is waaaaay out. Well, I hope no-one was paid to cast an editorial eye over it, at least…

As for Innes, sure — the killers are pretty easy to spot in the first couple, but he’s engaging in the genre with better intentions than simply reheating stuff we’ve seen elsewhere (the book under discussion being, I feel, a perfect counter-point). I want to get back to his fourth one soon, but,m man, there are so many books to read at the moment… 🙂

LikeLike

I really shouldn’t write my comments after going for a run! Sorry for the typos!

Innes hasn’t won me over yet, but I’ll grant him that both books were good company but had too much angst at the same time. I hope he tones it down, but it seems unlikely given that the books are labelled as “lgbt mystery” . But they’re also cheap so I’ll probably keep reading them though the next one might have to wait a little( I assume I’ll be very busy with American Mystery Classics!)

LikeLike

Oooo, good thinking — I’ll put all my typos down to running, too. I really shouldn’t write posts or comments while out for a run…embarrassing to have all these typos in them for that reason 😛

There is a sufficiently reduced amount of angst in Ripples compared to Untouchable, and it’s less dramatically framed than Confessional, so I think it’s just him finding his feet tone-wise. Apparently they start to get a bit darker as they go, I believe, so it’ll be interesting to see how that presents itself.

LikeLike

“I’ve finished the first two by Innes… I think that TomCat will have no problem starting from Ripples and going back.”

Excellent! Lately, I have added quite a few locked room mysteries to the big pile and wanted to read them before adding even more to it, but Innes was going to upset that plan. Now I’ll be reading Ripples first. And, if I like it, I’ll get the rest of them.

LikeLike

Even more time freed up to find us a fabulous locked room or two! Get to it!

LikeLike

Once again, thanks for taking the bullet on this one. I’ve been eyeing The Magic Bullet ever since it was published, but, like Yannis, evaded it due to its price and the fact that it was a Holmesian pastiche, of sorts.

I know there’s an audience for Holmesian pastiches, but, as a snobbish purist, they rarely appeal to me. When you take someone else’s creations, you better make sure they’re as close to the original as possible. You can always add a little bit of yourself (e.g. The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes), but it has to stand very close to the source material. Jill Paton Walsh’s Thrones, Dominations and A Presumption of Death are good examples of how to write a damn good pastiche.

So, yeah, I’ll scratch The Magic Bullet off my wish list.

LikeLike

I would love to know your reaxtion to the failure of the murder method, I have to say. It escalated me to a state of blank incredulity that someone would make you wait that long and work that hard for something that, at a single glance, can be seen to not even make sense. Aaah, well, you’re better off without it in your life. Go and discover something wonderful in the same you’ve now saved!

Re: Holmes pastiches, it was the Carr stories which got me even entertaining the notion of non-Doyle Holmes, and from there I’ve read more than a few: the Horowitz books (which I’m on record as loving), some Laruie R. King (which I’m not on record as having any feelings about), the Stepehn King short (which I really liked), the Colin Dexter one (which I love), some David Stuart Davies (which I hated), the Caleb Carr (which I gave up on), Ed Hoch’s collection (which were…fine, but also irritated the hell outta me), even an unpublished and very high quality pastiche from a fellow blogger (you can speculate amongst yourselvs over that one)…yup, Carr really opened some floodgates there!

I still hold out hope of finding the Porges Stately Homes stories for sensible money, because I’d be fascinated to see his take on the character, and I hope and hope and hope that Horowitz produces a third pastiche at some point. They’ve given me a new appreciation of how a character can alter so much and yet remain essentially the same, and the brief look we get at Holmes and Watson in this one make me believe that Millett would do a decent job of them…but it’s difficult to trust him after the plot fails so gigantically here. Though, well, I’m reluctant to give up on anything too quickly, so I may pick one up, you never know…

LikeLike

Sad to see another potential good modern locked room mystery not really be that good, I’ll just have to buy every Robert Innes book instead.

Hope you enjoy Nine – And Death Makes Ten. It’s incredibly superior to The Spanish Cape Mystery and will likely relieve any pain you feel from reading that slog 🙃

LikeLike

NADMT is, thus far, a delight — that may change, but at least the experience of reading it is more enjoyable than that of Spanish Cape. I’m genuinely sorry to always appear to have such a downer on EQ, but thus far they’re only sporadiaclly anything close to the vague idea of the authors their reputation would tell you they are.

As for The Magic Bullet, it is a shame to see such a detailed and hopefully well-intentioned homage go so very wrong. I know impossible crime novels are difficult to write — hell, novels are difficult to write — but that’s no excuse for such a poorly-realised scheme that obviously does not work. Like — how was that allowed to happen?!?!

Ah, sweet mystery of life…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not to worry, I don’t really enjoy first period Queen either. I remember being a young and curious GAD reader who was fascinated by the plot summaries and titles of the early Queens only to have my hopes severely crushed by just how boring the books turned out to be. The writing style was verbose to an extreme and made it difficult to read for my young brain. There were a few gems, GCM and STM where both delicious works – but the rest just seemed subpar in comparison to the hype. TSCM has a plot that is incredibly obvious from the start and offers little to nothing in terms of payoff (except for a few juicy deductions and a dream sequence). His Wrightsville novels might be slight on mystery, but are much, much better overall.NADMT is one of Carr’s classics. Little to no bothersome comedy, a stunning atmosphere, and a solution that will take all of your breath away in a snap.

Not much to add to your last paragraph, just that I agree with it completely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a particular scene in NADMT that seems relatively innocent at first read but in hindsight may be Carr’s most humorous moment.

LikeLike

Are you referring to the end of chapter 13? Just got to that, and it’s a great little joke…

LikeLike

I’m grateful for the reassurance! Perhaps I’m better off abandoning my long-held belieef about chronology in the case of Queen; there seems to be such a wild variation, that in order to read all of it one needs some reassurancers that overall it’s worth it — Siamese Twin, Greek Coffin, Chinese Orange, etc. Halfway house is on the way, so perhaps I’ll start again from thre if it goes well…though, if it doesn’t, maybe a break will be in order to get in more Berrow, Brand, Blyton, Carr, Crofts, Gardner, Huxley, Lorac, MacDonald, Penny, Rhode, Scarlett, Wade…yeah, I think I’ll be okay 🙂

LikeLike

So now that you have given up on Spanish Cape, may I recommend reading Siamese twin before The Halfway House. ST is a real gem, arguably even better than Greek Coffin.

LikeLike

I don’t think I’m going to have time to read it before HH now, not it Colin and I want time to dissect it properly and I want to get on with the others in my TBR. But I definitely won’t wait until I loop back around to read it. Prhaps I’ll do HH, then ST, and then carry on from there.

But, yeah, thanks for the vote of confidence in that one — I’ll get to it before too long. Ellery Queen In Order has definitely been abandoned…

LikeLike

I haven’t read HH yet so I’ll read along with you and we can see if it’s really the oasis between The First Period and The Hollywood Era or if it’s another disappointment.

If you need some more reassurance, I actually don’t hate The Door Between. Sure – the impossibility needs an amount of good luck that would make some of the flimsiest impossibilities look perfectly stable, but overall it isn’t excruciating painful and there’s a decent ghastly revelation at the end as well. Some of the stuff around the impossibility isn’t that great though.

I have to get to Berrow soon, The Bishop’s Sword certainly looks tempting but The Three Tiers of Fantasy is giving it a run for it’s money.

LikeLike

I’ll be interested to see everyone’s thoughts on “Halfway House” and on my suggestion that it is in fact more of a Period One book than a Period Two one.

LikeLike

Current plan is for it to go up in the middle of October. October is also a TMWEM month, so there’s plenty to schedule…

LikeLike

Another bum deal, what the ratio of good to bad books now in this modern locked room endeavor? As an aside I was thinking that the Harry Houdini mysteries? They seem to be a selection of modern impossibles with interesting set-ups.

LikeLike

Tne Harry Houdini Mysteries by Daniel Stashower are…fine? I’ve read two — The Dime Museum Murders and The Floating Lady Murder — and neither is good enough to warrant a review plot-wise, but Stashower is a very talented writer with a superb ear and eye for his characters. As impossible crimes they’re hoary as all hell, however, and not something I’d recommend to anyone wanting to stretch their wings in the genre.

LikeLike

That’s good to hear (mainly to be aware!) I have the Floating Lady and had a skim through the first few pages. The writing is lovely as you say so I was hoping for good resolutions to the impossibilities. Is it always too much to ask?!!

LikeLike

TFL is especially egregious in that the solution it offers doesn’t match the events as described when the crime occurs. Fuming, I was!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So annoying, sounds like this book as well!

I felt like that with The Invisible Guest as well.

LikeLike