Something a little different today: knowing that I’m a fan of the Australian dramatist and novelist Malcolm ‘Max’ Afford, Tony Medawar — the closest thing the GAD firmament has to Indiana Jones — sent me a selection of Afford’s thus-far-uncollected short fiction, as found in a variety of Australian publications from the Golden Age, and I’ve read them and am going to write a little about each one.

Continue reading

Do you find yourself lulled into an erudite hebetude by too many stories blethering on instead of simply getting down to the plot and relevant incidents? Well, Max Afford’s fifth novel runs to 116 pages and probably doesn’t contain a single one that does not in some way contribute to the interpretations or solutions of the central conundrums. A sea-faring mystery in the Death on the Nile (1937) school, a small group of characters are gathered on a liner heading out from Sydney, Australia to some islands because…reasons…when mysterious phone calls, mysterious passengers, mysterious relationships, and mysterious pasts all converge for a cavalcade of enigmas wrapped in queries and shrouded in deepest sinisterlyness.

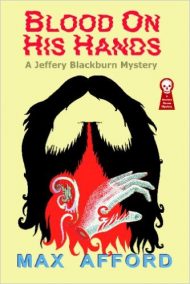

Do you find yourself lulled into an erudite hebetude by too many stories blethering on instead of simply getting down to the plot and relevant incidents? Well, Max Afford’s fifth novel runs to 116 pages and probably doesn’t contain a single one that does not in some way contribute to the interpretations or solutions of the central conundrums. A sea-faring mystery in the Death on the Nile (1937) school, a small group of characters are gathered on a liner heading out from Sydney, Australia to some islands because…reasons…when mysterious phone calls, mysterious passengers, mysterious relationships, and mysterious pasts all converge for a cavalcade of enigmas wrapped in queries and shrouded in deepest sinisterlyness. Philo Vance. ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ by Edgar Allan Poe. Raspberry Jam by Carolyn Wells. ‘The Fairy Tale of Father Brown’ by G.K. Chesterton. The Clue of the New Pin by Edgar Wallace. A character who is detective novelist of some repute. Characters in a detective story discussing whether they are behaving like people in a detective story. All these references and more can be found in the opening salvo of Max Afford’s debut novel, following the discovery of a man stabbed in the back in his locked study with the only key to the specially-constructed lock in his possession, the murder weapon missing, and some subtly esoteric clews that give rise to plenty of canny evaluation and then re-evaluation. Aaah, I love the Golden Age.

Philo Vance. ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ by Edgar Allan Poe. Raspberry Jam by Carolyn Wells. ‘The Fairy Tale of Father Brown’ by G.K. Chesterton. The Clue of the New Pin by Edgar Wallace. A character who is detective novelist of some repute. Characters in a detective story discussing whether they are behaving like people in a detective story. All these references and more can be found in the opening salvo of Max Afford’s debut novel, following the discovery of a man stabbed in the back in his locked study with the only key to the specially-constructed lock in his possession, the murder weapon missing, and some subtly esoteric clews that give rise to plenty of canny evaluation and then re-evaluation. Aaah, I love the Golden Age.

I believe the philosopher John Francis Bongiovi, Jr. said it best: “Keep the faith”. The Dead Are Blind is the third novel by Max Afford I’ve read and, having hugely enjoyed the other two, I found myself struggling to maintain interest through the opening chapters. Certainly from a historical perspective they have plenty to offer – our lead characters are invited to tour a radio studio on its opening night, something of a gala event at the time, and so this is chock-full of fascinating tidbits from Afford’s own experience of working in radio. But the mix of dense description and fixation on minute details that are hugely unlikely to become relevant later puzzled even my will and left me a bit apathetic by the end of chapter two.

I believe the philosopher John Francis Bongiovi, Jr. said it best: “Keep the faith”. The Dead Are Blind is the third novel by Max Afford I’ve read and, having hugely enjoyed the other two, I found myself struggling to maintain interest through the opening chapters. Certainly from a historical perspective they have plenty to offer – our lead characters are invited to tour a radio studio on its opening night, something of a gala event at the time, and so this is chock-full of fascinating tidbits from Afford’s own experience of working in radio. But the mix of dense description and fixation on minute details that are hugely unlikely to become relevant later puzzled even my will and left me a bit apathetic by the end of chapter two.