Genius Amateur

#590: Mystery at Olympia, a.k.a. Murder at the Motor Show (1935) by John Rhode

While Freeman Wills Crofts’ work has caused me much delight over the last few years, that of his fellow ‘Humdrum’ John Rhode/Miles Burton doesn’t inspire in me quite the same raptures. Rhode (as I’ll call him here) writes swift, events-focussed novels, and constructs plots with the same deliberation and consideration from multiple sides…so maybe it’s that his plots always feel like a single idea with some people bolted onto it. Here as in Death Leaves No Card (1944) or Invisible Weapons (1938) I come away with the impression that he read about a single obscure murder method and thought “Yeah, I can get 60,000 words out of that”.

Continue reading

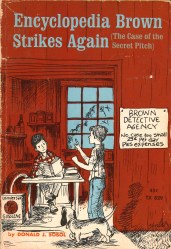

#586: Minor Felonies – Encyclopedia Brown Strikes Again, a.k.a. The Case of the Secret Pitch [ss] (1965) by Donald J. Sobol

Since starting this blog, I have made the acquaintance of The Three Investigators, the Five Find-Outers, and several other juvenile sleuths, the majority of who have been an absolute delight to encounter; today, I add Leroy ‘Encyclopedia’ Brown to that list.

Continue reading

#578: She Died a Lady (1943) by Carter Dickson

Firstly, good heavens the excitement of posting a John Dickson Carr review without then tagging it OOP — Polygon Books have Hag’s Nook (1933), The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941), and She Died a Lady (1943) in their stable, and the British Library and Otto Penzler have added more, with more to come. And after last week’s brilliant and baffling no-footprints murder in a lonely corner of England, and with my broadly chronological reading of Carr’s work bringing She Died a Lady back into my orbit, the stars seemed to be aligning on a reassessment of this, probably the most consistent contender for Best Carr Novel of All Time.

Continue reading

#575: The Gold Watch (2019) by Paul Halter [trans. John Pugmire 2019]

Similar to how Alfred Hitchcock’s two version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934/1956) use the same core ideas but differ in details, the motifs Paul Halter returns to in The Gold Watch (2019, tr. 2019) — the dual time period narratives of The Picture from the Past (1995, tr. 2014), a baffling no footprints murder at an isolated house a la The Lord of Misrule (1994, tr. 2006), the invocation of The King in Yellow from ‘The Yellow Book’ (2017, tr. 2017) — there’s no doubt this is a very different style of story simply using familiar ideas to very new ends. Strange to say this of a Frenchman, but this is perhaps the outright Frenchest work of his yet translated.

Continue reading

#536: The Futile Alibis – These Daisies Told: The Casebook of Professor Ulysses Price Middlebie [ss] (1962-75) by Arthur Porges

The work of Arthur Porges in the field of impossible and baffling crimes carries a salutary lesson: do not mess with mathematicians.

Continue reading

#504: Little Fictions – ‘The Helm of Hades’ (2019) by Paul Halter [trans. John Pugmire 2019] + Ranking the Translated Short Stories

Who doesn’t love a list? No-one who matters, that’s who. And since I’ve now read all twenty of the translated short stories of Paul Halter it seems inevitable that I should have my own preferences laid out for everyone to disagree with.

Continue reading

#502: The Door Between (1937) by Ellery Queen

Brad has threatened to drum me out of the GAD Club Members’ Bar for my lack of kow-towing to the work of Ellery Queen. In fairness, I really rather enjoyed Halfway House (1936), but here I am fighting for my rights. And I think he’s timed this deliberately, being well aware that The Door Between (1937) was up next for me, because Gordon’s beer is Eva MacClure, the heroine who finds herself at the centre of an impossible murder plot, one of the most frustrating perspective characters I’ve yet encountered. Goodness, she makes one positively ache for the company of Noel Wells from The Saltmarsh Murders (1932) by Gladys Mitchell.

Continue reading

#501: Little Fictions – The Uncollected Paul Halter: ‘The Wolf of Fenrir’ (2014) and ‘The Scarecrow’s Revenge’ (2015) [trans. John Pugmire 2015/2016]