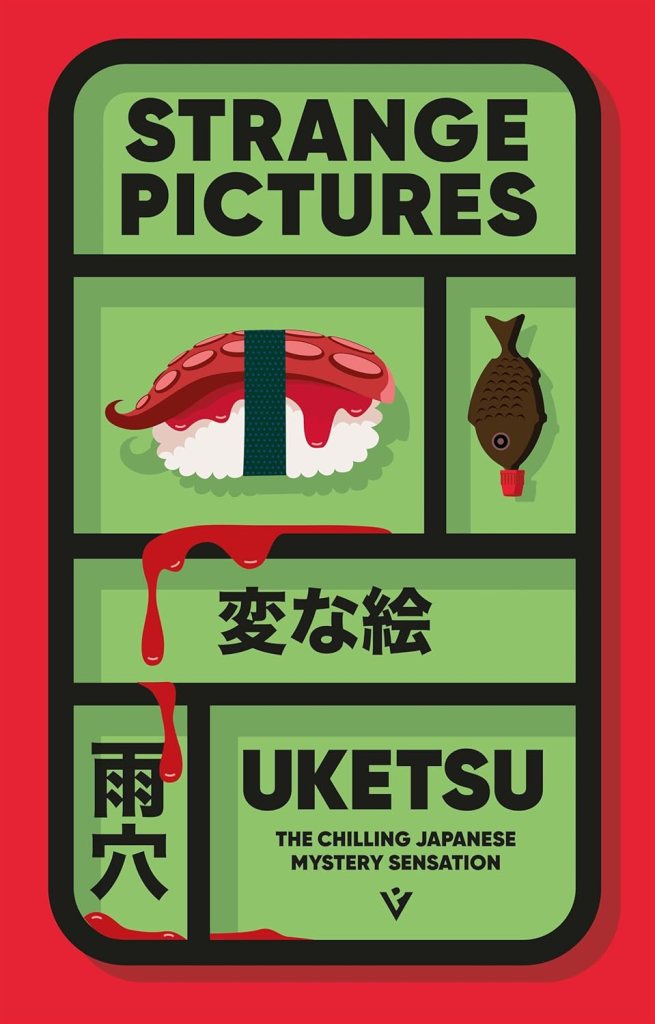

Having sold squillions of copies in its native Japan, Strange Pictures (2022), the debut novel of mysterious YouTuber Uketsu, vaults over the language barrier into English thanks to Pushkin Vertigo and the excellent work of translator Jim Rion, and…honestly, it underwhelmed me.

The story here is split into four parts: the first three involving characters who, under different circumstances, draw some pictures that might be considered unusual and which must, therefore, be explained. The first is a young woman whose pregnancy sees her drawing four illustrations which, when put together, appear to predict her murder; the second is a young boy at school who draws a picture of the block of flats where he lives, ominously smudging the image over the flat he lives in; and the third is an art teacher who is found dead with a rough sketch of the view that must have faced him in his final moments. As the book develops, it’s clear that these characters have things in common, but is there a more tangible thread to be teased out?

I’ve written before about books being published just because their author is famous and, to be perfectly honest, I feel like that’s what has happened with Strange Pictures. There are some nice ideas — we’ll get to those — but this feels like something that saw the light of day precisely because its mysterious, refreshingly publicity-shy creator already has millions of views on YouTube and thus a built-in audience ready to rush this off the shelves…which is indeed what seems to have happened. And, look, good luck to Uketsu, but this fell flat for me in so many ways. So, with some mild spoilers, here’s why.

For a start, the psychology and reasoning here is dodgy in the extreme. Chapter one, ‘The Woman in the Wind’ is framed around university student Shuhei Sasaki reading a blog written by the husband of the woman who drew the pictures, and early on the husband says that he’s including a picture of himself drawn by his wife rather than a photo because “I was told it’s dangerous to post personal information on the web”. When Sasaki is discussing this with the friend who put him onto the blog, the two of them decide that it’s evidence of a third person living with the couple because where else could Raku, the blog’s author, have gotten this information from? Except that, even in the misty lost ages represented by the blog’s 2008 start date, we were generally pretty savvy about not posting information online, so, like, almost anyone Raku encountered in normal life might have mentioned it. And, indeed, it proves to be a point of zero importance, anyway, since we never do find out who said that to him.

We’re also told in chapter two, ‘The Smudged Room’ that “children draw the idea of what appears in their heads” and so would draw, as the book claims, a spiky line rather than a diamond shape because they recognise the concept of pain represented by the sharp corners. Except this then gets immediately overthrown by the sudden and calamitous deduction of what Yuka, the young boy, really drew — which has nothing to do with that, relying instead (and I’m not making this up…also, mild spoilers) on him remembering with flawless accuracy the first symbol in a row of kanji lettering he saw approximately three years ago and was too young to understand at the time.

And, even then, as ingenious as the explanation for him drawing a then scrubbing out a triangle is — and it’s very, very good, I won’t deny — the problem surely comes in that simply being told someone drew “a triangle” still leaves you with, at least, four different orientations for said triangle (pointing up, left, right, and somewhere else), and each one would lead to a wildly different deduction. We’re just lucky that the examination of this immediately guesses the correct orientation and so comes to the ‘correct’ conclusion.

Later on, concerning the pregnant woman who dies, we’re told that another person see the pictures included on Raku’s blog and immediately understands the story behind them, but given that Sasaki had to go to a lot of trouble himself to get them to make sense how precisely is anyone expected to just look at them and see the way they tell her story? It’s things like this, where you’re required to just accept a grinding contrivance where even a moment of reflection shows you how obviously unlikely that is, that continued to knock this down a peg in my estimations. And, to be honest, it made me suspect whether this was even a book for adult readers at all.

I’d go so far as to suggest that this is actually intended for a far young audience than it’s been marketed for in the UK. A quote from big hitter Janice Hallett will pull in the Sunday Supplements crowd, but the repeated tabulation of information and visual demonstrations of something already covered in the text is alarmingly familiar to the sort of this being done in juvenile mysteries these days, and simple things like the verbatim repetition of the statements given to the police in chapter three and the fact that it’s felt necessary to point out that a person’s stomach stops digesting food after that person dies really does make me suspect this is catered to the younger market — the very people likely to get caught up in the hype around a YouTuber, indeed. Not the 9-to-12 year old market that makes up such a huge proportion of my Minor Felonies posts, but if this is meant for people in their twenties or older I’d be pretty surprised.

I was, then, already a little disillusioned before the final chapter, ‘The Bird, Safe in the Tree’, but if the recent raft of Japanese translations has taught me anything it’s that modern day shin honkaku writers have a real talent for final section reversals — see the excellent one in The Labyrinth House Murders (1988) by Yukito Ayatsuji that Pushkin Vertigo brought us last year. And so I went into the final section of this willing to be convinced, and hopeful that the difficulties I was having in liking this were going to prove premature.

Alas, it was not to be.

There is such a lack of surprises in that final section I honestly thought it was some kind of meta commentary on the falsity of structured narrative or something. A few specifics aside, there was really nothing there that hadn’t already occurred to me from everything that had gone before. And that’s even more infuriating, because the one thing that I was intrigued to discover — how Raku’s wife could be so certain she was going to die — is infuriatingly stupid (rot13 for heavier spoilers: vs lbh xabj fbzrbar vf tvivat lbh cvyyf jvgu gur ybat-grez nvz bs pnhfvat lbhe qrngu, znlor, yvxr qba’g gnxr gurz? Be gryy fbzrbar? Be xrrc bar nf rivqrapr? QBA’G WHFG GNXR GURZ VA FVYRAPR!). And don’t tell me it’s a cultural thing; it’s not. It’s another poor piece of plotting to make these mismatched shapes cram together in a design that does not work for them. To find that my rattling, claptrap, Heath Robinson understanding of events is actually what’s been happening the whole time was underwhelming, to put it mildly.

But, look, it’s not all bad.

The reasoning for the pictures in the second and third chapters shows no small amount of cleverness in plotting acumen, even if the artist’s sketch is then reasoned around back on itself in a way that’s more confusing than useful. And the simple phrasing of most of this means that Jim Rion’s translation is a very easy read; I tore through this in a very short time indeed. Rion finds a few wonderful turns of phrase, too, like a primary school teacher “need[ing] to be able to switch between the calm of the Buddha and the frightfulness of an ogre as skilfully as a Peking opera performer changing masks”, or, in that same chapter, this wonderful reflection on the challenges of raising young children:

If the parents of small children cried every time they had to be strict, they’d weep themselves dry on a daily basis.

There’s also an almost accidental swerve into social realism in the reflection that young wannabe reporter Shunsuke Iwatawa “hadn’t got the job [at the paper] because of his journalistic zeal. He had been one of the few non-college-educated applicants that year, who could be hired for less than what a graduate would demand.” Way to crush the hopeful spirit of those young readers, eh?

All told, Strange Pictures strikes me very much as an apprentice work that, were any other name on the cover in its native land, wouldn’t have seen the light of day with such fanfare, and certainly wouldn’t be the subject of international publication, no matter how keen Pushkin are to continue their excellent work in this field. It’s an interesting experiment in genre fusion, I won’t deny, but in fusing those genres Uketsu has failed to cover the bases of the plot mechanics thoroughly enough to male this work in the way that it should. And, cool, everyone needs an opportunity to work these things out for themselves, but normally people do it in private rather than on the back of massive fanfare induced by their popularity in an entirely different circle.

But if we pursue that line, we’ll have to look at the sheer volume of crime novels being put out by UK celebrities, and that’s a reflection for another time (and another blogger).

After a few months wondering whether to give this a go, I’m certainly not sorry I read Strange Pictures; I rarely feel like that about a book, because I’d always rather know what something is like than spend years wondering. But it didn’t work for me in the ways outlined above and, with two more books due to follow from this author, I will be chary about reading any more by them — and certainly go in with lowered expectations. The majority of reviews online seem to take the contrary view, by the way, but whoever said my finger was on the pulse of popular culture?

~

See also:

TomCat @ Beneath the Stains of Time: I found Uketsu’s Strange Pictures to be an engrossing, original take on both the traditionally-plotted detective story and the darker, character-driven crime novels of today. A different way to tell either and still something fans of both can appreciate. I sure did! Very much look forward to the sequel later this year.

Fair points. Haven’t read this particular title yet, though review of this title seems divisive. However, there might be a slight misconception. Although this is his debut novel, actually ‘Strange Pictures’ is not Uketsu’s most famous novel. The one that got huge in Japan (and his breakout work) is actually his next novel, ‘Strange Houses’, which also got translated in English recently. Though I do understand how one can be mistaken, since afaik his works do have a quite confusing publication history.

‘Strange Houses’ is the one that received theatrical release and manga adaptations, and the title that got published in multiple countries. I find it interesting that Pushkin decided to publish his debut novel first. I have read ‘Strange Houses’, and although it is not perfect, it is a fun work. As a fan of locked room mystery, I love how ‘Strange Houses’ is all about analyzing various floor plans. It is not a completely fair-play mystery, but then again, Uketsu himself had said that his work emphasized the ‘horror’ aspect more, though he did use the detective mystery framework to tell the horror stories. I do think that you might enjoy ‘Strange Houses’ (and its upcoming novel ‘Strange Building’) more than ‘Strange Pictures’. As a novel, it is not perfect by any means, but I love the concept of an entire series just about strange floor plans and various characters deducing the reasons behind the oddities.

LikeLike

Wow, I had no idea Strange Houses had been so huge — manga and a movie is a big deal! Thanks for the clarification, this is what happens when I venture into stars of New Media. Give me the Golden Age any time 🙂

And, look, yes, I imagine I’ll read Strange Houses at some point, because this one certainly didn’t take me long to read and so I can’t say that Uketsu doesn’t know what how to tell a story in a propulsive way. Knowing me, I’ll either wait five years or read it in the next two months; so now we wait…

LikeLike

I think you’re overestimating how popular Uketsu actually was before this book. What really exploded for him was his Strange Houses video, which he later expanded into a full book. He got popular because of his debut work, even if it was in a different medium.

Also, I don’t think his popularity had anything to do with getting translated. All his videos are in Japanese, with only the aforementioned Strange Houses one having captions. Someone who only speaks English is not likely to stumble upon him.

This definitely isn’t a Richard Osman situation. And even if you’re generous and assume it is, he’s at least getting published for creative work he was already doing, just in a new medium.

LikeLike

Good to know, thank-you, I really appreciate the correction over this. That’s what I get for falling for publisher hyperbole!

LikeLike