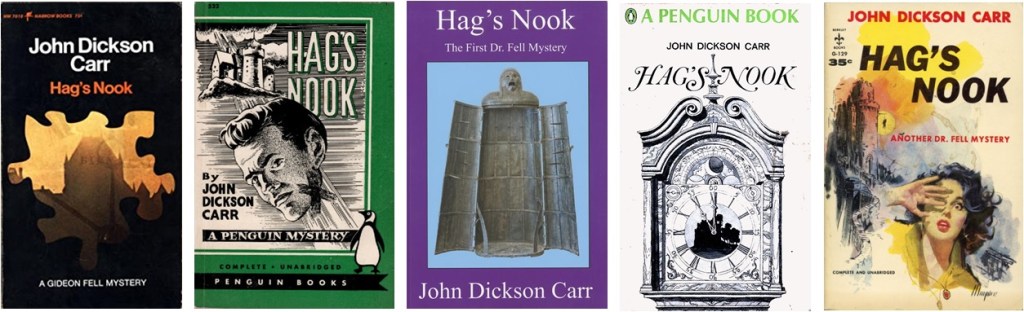

A (fairly) recent review of Hag’s Nook (1933) by John Dickson Carr at Tangled Yarns added to its (slightly less) recent reprinting by Polygon Books put this first appearance by Dr. Gideon Fell on my Hallowe’en reading list…and here we are. A family curse — “the Starberths die of broken necks” — seems as good a topic as any for this annual celebration of eldritch horrors, so let’s dive back in and see what I make of it some ten or more years after my first read.

I feel that there’s a tendency to look upon Hag’s Nook as the beginning of Carr’s detective fiction career proper — it’s certainly a deliberate step up from the macabre atmospherics of the four novels featuring Parisian sleuth Henri Bencolin which preceded it — even though that honour arguably falls to his oft-overlooked country house puzzler Poison in Jest (1932). The added weight this book carries comes, of course, from the presence of Dr. Fell, who would go on to feature in 23 novels — approximately ten of them masterpieces — over the next 35 years and become one of the Golden Age’s most beloved sleuths (c.f. his number one seeding in the set of polls currently running on this very blog). In a way, this is an inauspicious debut for Fell: he’s very good at raising objections and pointing out inconsistencies, but come the finale it’s the criminal who confesses rather than the detective (claiming to have known everything anyway…) who dazzles us with his insight. At this stage, there’s nothing to suggest the good doctor would have a longer life than M. Bencolin, even though we can be very grateful that he did.

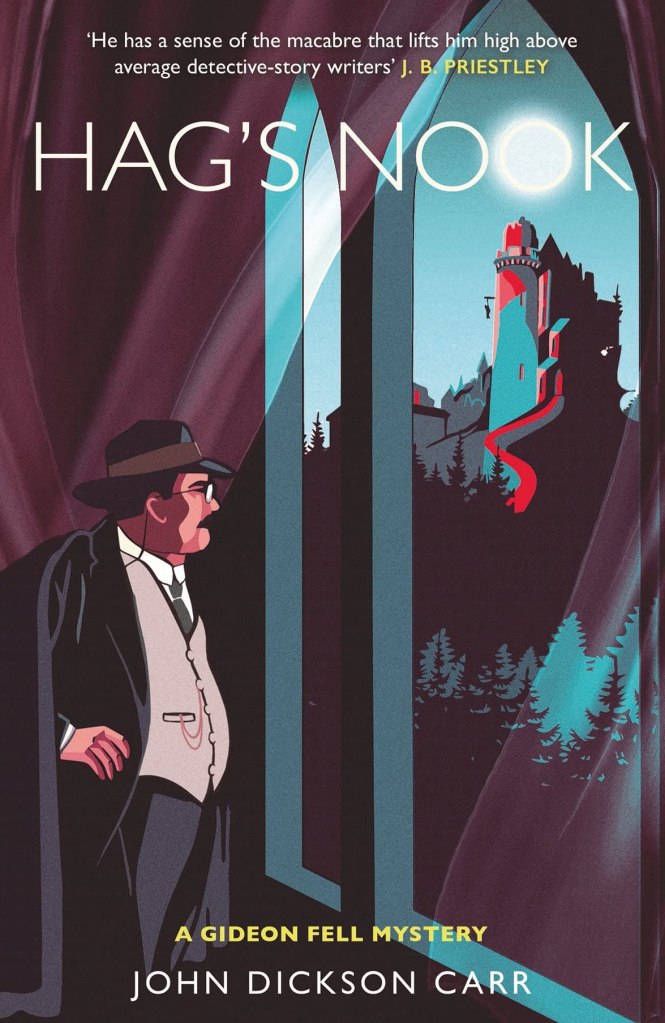

The plot concerns the Starberth family, squires of the village of Chatterham in Lincolnshire, who have the sort of tradition that has probably fallen out of favour these days, to the detriment of the noble classes. Upon their 25th birthday, the eldest Starberth male must spend the hour after midnight in the warden’s office of the now decrepit Chatterham prison in order to inherit their father’s wealth. Certain safeguards and conditions are put in place to ensure this obligation is fulfilled, not least that there is a secret, possibly a terrible one, that the heir will learn as a result of his vigil. Tonight, it is the turn of Martin Starberth — that’s Martin, not Marin, as my Polygon edition says, three times, on its back cover — who must sit, wait, and hope that the curse of broken necks does not fall upon him.

And, well, what do you think happens?

Carr learned how to induce a shiver with the Bencolin novels, and is quick to put shuddersome principles before you by hoeing hard at the superstition-leaden earth with enriches so many of England’s byways:

In Germany even the legends have a bustling clockwork freshness, like a walking toy from Nuremberg. But this English earth seems (incredibly) even older than its ivy-bearded towers. The bells at twilight seem to be bells across the centuries; there is a great stillness, through which ghosts step, and Robin Hood has not strayed from it even yet.

Spectres are taken almost as read (“If you see any ghosts, save them for me.”), and against this dismal background the silhouette of the prison, abandoned centuries ago following a cholera outbreak (“It was the cholera, of course; cholera — and something else. But they said the other thing was worse.”) and now looming ominously on the skyline, imposes a sense of alacrity upon the denizens of Chatterham that American Tad Rampole, visiting Fell on account of a common acquaintance, finds hard to comprehend:

“I’m not trying to scare you with ghost stories,” [Fell] added, after he had sucked wheezingly on the cigar for a time. “I’m only trying to prepare you. We haven’t your American briskness. It’s in the air; the whole countryside is full of belief. So don’t laugh if you hear about Peggy-with-the-Lantern, or the imp on Lincoln cathedral, or, more particularly, anything concerned with the prison.”

With Martin ensconced in the office at the given time, Fell, Rampole, and the rector Thomas Saunders wait at Fell’s house, watching the light of his lamp through the distant prison window…only for it to go out ten minutes early and Rampole, rushing to the scene, to discover Martin Starberth flung from the balcony of the warden’s office and lying dead next to the eponymous well where prisoners had been hanged for generations. Much freezing of blood occurs in a traipse through the sinister prison to reach the room from which Martin had been thrown — though I must say, Carr would outstrip this with the seriously spooky prison visit in The Skeleton in the Clock (1948) under his Carter Dickson nom de plume — and Fell will, in due course, spot several little details which don’t add up in what is the intended accepted version of events. So…whodunnit?

Carr being Carr, he’s not content even at this early stage in his career merely to unsettle you, though he does that admirably:

“That was the turnkeys’ waiting-room, and the prison office beyond it,” Dr. Fell amplified. “There was where the governor interviewed his guests and recorded ’em before they were assigned their quarters.”

“It’s full of rats, anyway,” Rampole said, so suddenly that they all glanced at him.

The earthy, cellary smell of the place still seemed to be about him as it had been last night. “It’s full of rats,” he repeated.

Right from the off, having stirred the pot of sinister forces and apparitions, he’s able to switch moods on you in the blink of an eye — giving you the cosy domesticity of the Fell menage, a stir of romance as Rampole (in what would become a staple of Carr’s writing) almost instantly falls in love with Martin’s younger sister, Dorothy, and even some wonderfully-observed comedy in the sixth chapter, ‘Midnight Comes Too Soon’, told from the perspective of Mr. Budge, the Starberth’s elderly retainer. There’s a real sense, too, of the paralysis that this curse and tradition have imposed upon the family, seen most clearly in our first visit to the Starberth house as outsiders:

Silver chimes rang with fluid grace from the great clock in the hall, sounding as though they were striking through the vault of a cathedral. In this library everything looked old and solid and conventional; there was a globe-map which nobody ever spun, rows of accepted authors which nobody ever read, and above the mantelpiece a large mounted swordfish which (you were convinced) nobody had ever caught. A glass ball was hung up in one window, as a charm against witches.

And, crucial to this juggling of tones, Carr has also learned when to pull back, how to avoid smothering the reader as he could at times (Castle Skull (1931) springs to mind), how to lead us up to the edge of horror and then throw wide the curtains to show that he’s been unnerving you against the background of a gorgeous Spring day that can banish any and all demons:

When she opened the great door for him, it seemed surprising to find the placid sunlight on the lawns as though this were only an English Sunday and no dead man lay upstairs. We are not touched so deeply by tragedy as we think.

That study in contrasts is the most successful element of this, and really shows the young Carr maturing as a writer — the eerie sense of wrongness brought about by wet things clambering over walls, or tapping at doors only works if you believe in the situation and the people involved…you can only pop a balloon once, after all, but Carr yoyos his setting and characters brilliantly throughout, deflating a situation only find a new way to fill it with unease over and over again, so that come the end you’re not entirely sure what’s corporeal and what can be laid at the heels and made to account for itself.

I can fault this in the writing only in that the cast is too compact for it to work as a proper whodunnit, since, as we expect the criminal to be someone known to us, there’s only really one suspect…though, in fairness, we are misdirected away from them by a very clever piece of legerdemain. The individual characters are captured with an insight that would serve Carr well in the years ahead — see Saunders “shovelling out platitudes like a pious stoker, with the idea that in quantity there was consolation” or “trying to apply the rules of English sports, suddenly, to a dark and terrible thing; and…not find[ing] their application” — but there are very few hands in the pot and only really can be forcing things…even if you need to wait until their confession to find out how.

In revisiting Hag’s Nook, I have an increased respect for this opening salvo of Fell’s long and distinguished career. The central misdirection struck me much more favourably this time around, and Fell’s level-headed assessment of the Starberth curse, coming sooner in the book than I remember, opens up the second half to a much more traditional mystery plot. Even the MacGuffin, which I heartily disliked on my first read, makes more sense to me this time, occupying as it does far less of the narrative than I remember and being sprung as far less of a surprise. The final line, too, is exquisite, and had somehow completely escaped my memory — a fault I have addressed now, as that image will stay with me for a long time. All told, then, this second read revealed Hag’s Nook as a more promising start than my memory was willing to admit to a career would see both author and sleuth improve to the wildest heights of the Golden Age. A lovely experience to come to it again, shudder afresh, and leave so satisfied.

~

See also

Mike @ Only Detect: In a gripping discussion of the clue-rich site where Martin spent his last hour of life, Fell interjects a bit of literary criticism that signals the nature and scope of Carr’s ambition. The Gothic romance, with its panoply of carefully laid death traps and other grotesque improbabilities, lags “far behind the detective stories,” Fell contends. Tales of detection, he says, “may reach an improbable conclusion, but they get there on the strength of good, sound, improbable evidence that’s in plain sight.” Measured by that standard, this book succeeds…Carr’s commitment to the fair-play ethos entails no sacrifice of his ability to deliver thrills and chills on a Gothic scale.

James Scott Byrnside: The clues are fair but obscure. There’s some confusion about fair play. One does not need to be able to solve a mystery for it to be fair, rather one must have the tools to solve it at his/her disposal. Arguing that no one can solve it is very different than arguing that the solution comes out of left field. Hag’s Nook plays fair, even dangling the evidence in ways that can easily be misinterpreted.

Budge for sure was one of my favorite parts of the novel, and maybe my favorite non-Fell character in the novel. There’s something absurdly hilarious about him; it’s almost like somebody took Joseph from Wuthering Heights, brushed him up a bit, and dropped him into the 1930s without any warning. As a comic relief, he works very well. And that last line really is something, isn’t it?

LikeLike

This at least shows Carr doing comedy more successfully than in his ostensibly “funny” novel The Blind Barber — a somewhat bawdy and unusual effort from Carr, albeit with a great piece of misdirection at its heart. Indeed, he’s often at his funniest when least expected: Constant Suicides is a brilliantly humorous book, but then I think Fell — who tends to be less self-serious than Merrivale — was easily Carr’s funniest creation…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You mention that 10 of the Gideon Fell books are masterpieces. Would you share which those are? I’ve read and enjoyed several; I know I won’t be able to read all 23, but 10 would be doable. And thanks for this review, I think a re-reading of Hag’s Nook is now in order.

LikeLike

Always happy to help with Carr recommendations 🙂 Chronologically, I’d suggest the pinnacle of Fell is:

The Mad Hatter Mystery (1933)

The Eight of Swords (1934)

Death Watch (1934)

The Hollow Man (1935)

The Black Spectacles (1939)

The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940)

The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941)

The Seat of the Scornful (1941)

Till Death Do Us Part (1944)

He Who Whispers (1946)

Below Suspicion (1949)

Hopefully that helps your task somewhat, not least because quite a few of them are now — or soon to be — back in print. And, when you’ve done the best of Fell, don’t forget that there’s still plenty of non-Fell excellent both from JDC and his Carter Dickson nom de plume…

LikeLiked by 1 person

My tastes align with this list, and I think it’s illustrative (and somewhat contrary to conventional wisdom) that the slight majority of this list consists of titles from the 1940’s— indicating (along with the works of Christie and Brand) a later height of the Golden Age than is usually cited.

LikeLike

Perhaps it indicates a slightly later peak to the Golden Age, but remember that it’s also not selected from all of Carr — only the Fell novels. So it could be that including the best of all Carr skews things a little earlier or — more likely — it could be that Carr happened to have a longer peak than most authors (covering some 15 years, and thus taking in at least two decades).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incidentally, the best of Merrivale would, in my estimation, be:

The White Priory Murders (1934)

The Red Widow Murders (1935)

The Unicorn Murders (1935)

The Judas Window (1938)

The Reader is Warned (1939)

Nine–and Death Makes Ten (1940)

The Gilded Man (1942)

She Died a Lady (1943)

He Wouldn’t Kill Patience (1944)

That skews slightly earlier and averages out in the late 1930s…but then I’ve said before that I reckon the peak of GAD was around then, anyway, so maybe I’m on to something after all…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tell me that The Ten Teacups and The Judas Window were left off by mistake. Please!

Merrivale does indeed skew early. His best books are Plague Court through Nine and Death Makes Ten. After that his books are still good, but just not at the same level, with the exception of She Died a Lady and Patience. I’ll note that there’s a bit of a shift in writing style when that split occurs – humor is much more at the forefront in the second period, and air tight impossible crimes aren’t featured nearly as often.

LikeLike

The locked room shooting in TTT is amazing, but the book as a whole is — alas — really just three short story plots that don’t quite join up. Some wonderful individual moments (the disappearing body might be about the best reveal in the whoe of Carr’s output…) but not quite the cohesive whole those moments deserve.

And Crooked Hinge…look, I like it, but I feel it’s over-praised. The automaton is creepy and delightful but….doesn’t really go anywhere, and the reveal of the solution to the stabbing really needs a couple of extra pointers as to what’s going on (and could have them, too — someone really needs to let me go in and add a few lines to a couple of Carr books to make them copper-bottomed masterpieces!). Again, a very good book, but not one I can put on the same level as Seat of the Scornful or Till Death Do Us Part.

LikeLike

JIm, I feel similarly about Crooked Hinge, and I think your comment provides an excellent illustration of the subjective nature of clue sufficiency for, while the clueing of the solution to that novel is clearly insufficient for either of us, I doubt that we could agree on a precise level of clueing that would be sufficient— and even if we could, that would only indicate an alignment of our personal values, not a non-arbitrary, objective level of sufficiency. Of course, complete logical inescapability would satisfy both of us, but our stated opinions of other works clearly indicates that we don’t demand that level of sufficiency for our personal satisfaction.

LikeLike

“Sufficiency” is — as you quite rightly say — a difficult marker to agree on, and I don’t propose to know how to address that. I just wish TCH in particular did a little more to set up its eventual reveal: it seems to me Carr missed a trick by not including…certain marks…on the ground where the body is found. What an opportunity scuppered…!

LikeLike

I’m entirely with you in saying of CH, “there’s not enough clueing for my satisfaction.” I’m guessing our opinions of the novel are quite similar. But I’m also suggesting that that the reason we can’t pinpoint a logical standard of sufficiency is that there is actually none to pinpoint (short of the one level of level of sufficiency none of us considers necessary). The flaw in the general contemplation of clue sufficiency is the failure to recognize its entirely subjective nature.

LikeLike

Indeed I agree with you. Given the debate that ensues whenever someone tries to create a best list of his work, Carr at his peak was more prolific than other authors. In fact, other than Christie, what other GAD authors yielded the quality output that Carr did?

There are certainly other prolific authors like Bush, Flynn, Bellairs, etc., but their quality is more uneven. Christianna Brand is a particular favourite of mine, but her output was limited. I am now making my way through and enjoying the John Sladek titles, Black Aura and Invisible Green, based on TomCat’s and others’ recommendations including yours, but Sladek only wrote a couple GAD style novels and two short stories.

LikeLike

I wonder if the quality of Carr’s output (when he’s good) must also go hand-in-hand with his productivity: so, in order to find people who wrote as much good stuff as Carr you also need to consider first who else wrote as much as Carr. And that makes it trickier, right?

Carr and Christie both wrote about 80 books — far more than Bush and Flynn and others — but did anyone else close to or over 80 books (ECR Lorac, Anthony Gilbert, John Rhode, etc) write as well as AC and JDC? I don’t know how to unpick this, alas, but I’m certainly interested in anyone’s thoughts when it comes to very prolific authors who also wrote well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m more aligned with your H.M. picks. I really need to reread The Eight of Swords in English to properly judge it, but can’t see Death Watch or The Man Who Could Not Shudder making it onto my top 10. Below Suspicion is marginally better and more tolerable than Patrick Butler for the Defense, but I hate both of them and no idea what Carr was thinking when he created Patrick Butler. A character who should be boiled alive in his own bodily fluids! I would trade a few titles on your H.M. list, but can’t fault you for picking any of them as your favorites. All solid choices. Even the often overlooked and underrated The Gilded Man. How uncommonly perceptive of you! 😀

“In fact, other than Christie, what other GAD authors yielded the quality output that Carr did”

Christopher Bush, Erle Stanley Gardner and E.R. Punshon?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stopped clock that I am, this must be one of the two times a day I get something right 🙂

I like Patrick Butler, if only because I can’t help but feel that Carr created him — “The man who is never wrong”! — so that we can take a vicarious pleasure in watching things go very wrong for him…his pomposity, so unlike most of Carr’s protagonists, is the thing I find most endearing about him. Very much looking forward to making his acquaintance again.

I’m less sold on Bush and Punshon than you are but even I, arch defender and champion of Gardner, wouldn’t put what ESG did in the same bracket as Carr. Gardner at his best is entertaining and surprising, whereas Carr’s second tier can still be staggering in its ingenuity and ideas. Carr is usually memorbale, whereas Gardner entertains me and then flees my memory about a week later. Sure, the man was prolific, but he’s not in Carr’s league for quality of output.

I should also say, I’ve really enjoyed your recent posts, especially your revisit of Sladek, but every time I leave a comment Blogger swallows it never to be seen again. But I am reading and trying to engage with your blog, I promise!

LikeLike

I meant quality output by an author’s own standards. If you mean quality and consistency in general, then yes, Carr and Christie are in a league of their own.

No idea why blogger is acting up again. Nothing in the spam folder or comments awaiting approval, which is always turned off because don’t want any barriers for people to post comments.

LikeLike

Thank you! I’ve read The Mad Hatter – and concur with masterpiece status! – now onto book two.

LikeLike

Happy reading 🙂

LikeLike

Your list is missing the topic of this post. I really do think Hag’s Nook is one of Carr’s better overall novels. I love a good campy treasure hunt plot, and it’s even mixed with a ghost story. Plus, the solution is pretty fantastic and there’s a nice drawn out explanation.

As for the list – I’d lop off The Eight of Swords and add Hag’s Nook, The Arabian Nights Murder, The Crooked Hinge, and The Problem of the Wire Cage. I appreciate the inclusion of Below Suspicion, which doesn’t get much love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Structurally, Arabian Nights is a delight, but personally I found the actual telling of the story to be too drawn out…maybe I’ll enjoy it more second time around, like Hag’s Nook.

In a way, this is the nice thing about reading a book a second time: often, so much time has passed that I’m looking for different things on my second encounter and end up finding something new to enthuse about. Some books have struck me less favourably on second read, it’s true, but on the whole I have a pretty good track-record…

LikeLike

I had convinced myself after reading many post from bloggers who I respect to stop reading Carr’s later Fell novels after The Sleeping Sphinx so Below Suspicion never grabbed my attention particularly after learning the irritating Patrick Butler is there.

But now I see it on your list above and your five star review (you don’t give many of those on your blog) so will get this when an affordable copy makes itself available. Now I am curious what I have missed with Below Suspicion.

LikeLike

Later Carr is a tricky proposition — I’m into the 1950s myself, with the intention of reading everything — because, yes, the guy’s quality undoubtedly drops but…man, you just never know when he’s suddenly going to spark to life and produce something wonderful as his talent can.

Rest assured, I’ll be working though everything in due course, so any recommendations I stumble across will be talked about on here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Below Suspicion is definitely worth reading. It has the heart of Carr’s better historical romps, but it’s set in the present day. It has an interesting puzzle that borders on impossible crime, and a nice twist at the end. There’s a flaw in how the denouement is presented, but other than that it’s Carr’s last great Fell novel. Much better than The Sleeping Sphinx.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am thinking that this might deserve a revisit from me as I found it easier to appreciate than enjoy. It certainly feels like a transitional novel for Carr, but like you, I found the mystery plot to be rather lacking. And the atmosphere of horror that Carr is able to conjure here feels like it’s leading the way to bigger and better things too in The Three Coffins and The Plague Court Murders . Perhaps next time I ought to just let Carr take me on the journey with Dr. Fell and I should stop comparing it to his half-dozen other masterpieces.

LikeLike

Only half a dozen? Bold words, Nick… 😄

LikeLike

I definitely underestimated the number of masterpieces in the oeuvre. Of the 17 Carr titles I have read, I’d probably put the first 10 in the masterpiece category:

1. The Three Coffins

2. He Who Whispers

3. The Problem of the Green Capsule

4. The Crooked Hinge

5. The Burning Court

6. The Plague Court Murders

7. Til Death Do Us Part

8. The Red Widow Murders

9. The Case of the Constant Suicides

10. The Judas Window

11. She Died a Lady

12. The Seat of the Scornful

13. The Eight of Swords

14. Hag’s Nook

15. Castle Skull

16. It Walks By Night

17. The Mad Hatter Mystery

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a quite fabulous list of JDC books you’ve curated so far…and you still have another solid 10 or 15 excellent reads to go, you lucky man 🙂

LikeLike

SHE DIED LADY is one of my favourites but a top 10 for Carr is just too small a number!

LikeLike

Great review Jim. Like you, I liked it even better the second time round (admittedly, decades elapsed between readings).

LikeLike