- Comment

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

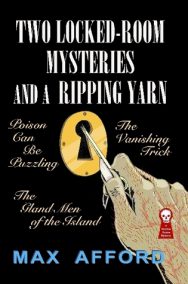

It’s not an especially long story (I’d estimate about 5,000 words) but the seeming impossibility does have a nice solution which, despite being stumbled upon by pleasant serendipity rather than pure detection, bears up to scrutiny and more than warrants a read. To establish a hermetically-sealed environment, some atmospheric backstory, an impossible crime, a nicely-worked piece of misdirection, a well-developed strand of paranoia, some half-decent clues, and a clear, concise, believable, well-motivated solution to everything in so little space is an achievement beyond a lot of novelists and evidence enough that Afford must have been pretty decent at his job (spoiler: he was). This is actually one of the better poisoning tales I’ve read, and among the very best impossible poisonings, and I thought I’d use it as a gateway to looking at the problems the method has faced in the past which always leave me a little apprehensive when it get utilised, and how this becomes an even better story for avoiding them so adroitly.

It’s not an especially long story (I’d estimate about 5,000 words) but the seeming impossibility does have a nice solution which, despite being stumbled upon by pleasant serendipity rather than pure detection, bears up to scrutiny and more than warrants a read. To establish a hermetically-sealed environment, some atmospheric backstory, an impossible crime, a nicely-worked piece of misdirection, a well-developed strand of paranoia, some half-decent clues, and a clear, concise, believable, well-motivated solution to everything in so little space is an achievement beyond a lot of novelists and evidence enough that Afford must have been pretty decent at his job (spoiler: he was). This is actually one of the better poisoning tales I’ve read, and among the very best impossible poisonings, and I thought I’d use it as a gateway to looking at the problems the method has faced in the past which always leave me a little apprehensive when it get utilised, and how this becomes an even better story for avoiding them so adroitly. Now, I use ‘himself’ in the previous sentence advisedly because we’ve also had to endure generations of patriarchal detectives confidently asserting that poison is a woman’s weapon as men are more likely to seek their vengeance in less subtle ways (presumably while talking about the football and asking what kind of car their victim drives). And what usually happens? The perpetrator turns out — oh, my sainted aunt — to be a man. It’s a misdirection as old as the hills and about as difficult to miss, but the absence of any other physical clues inevitably leads us into the realm of Amateur Psychology 101 and from their into questionable attitudes towards the fairer sex, or proclamations about the degenerate thinking of a criminal that a) age these classic stories so badly, and b) typically get forgotten when it turns out to be the sensible bank manager who was responsible. One interesting side-note to this is that I recently read a book contemporary to this which asserted that a stabbing was a feminine crime, which is surely a reversal of the usual attitude taken. Refreshing, but confusing. And besides, we all know that if the women of the 1930s stabbed anyone they’d risk dropping a stitch…

Now, I use ‘himself’ in the previous sentence advisedly because we’ve also had to endure generations of patriarchal detectives confidently asserting that poison is a woman’s weapon as men are more likely to seek their vengeance in less subtle ways (presumably while talking about the football and asking what kind of car their victim drives). And what usually happens? The perpetrator turns out — oh, my sainted aunt — to be a man. It’s a misdirection as old as the hills and about as difficult to miss, but the absence of any other physical clues inevitably leads us into the realm of Amateur Psychology 101 and from their into questionable attitudes towards the fairer sex, or proclamations about the degenerate thinking of a criminal that a) age these classic stories so badly, and b) typically get forgotten when it turns out to be the sensible bank manager who was responsible. One interesting side-note to this is that I recently read a book contemporary to this which asserted that a stabbing was a feminine crime, which is surely a reversal of the usual attitude taken. Refreshing, but confusing. And besides, we all know that if the women of the 1930s stabbed anyone they’d risk dropping a stitch…

”Blackburn is now married – this was written after the novels I’ve read to date, so I’m yet to discover if he utilised the standard Golden Age method of finding a spouse, ….”

But he found his future wife in Owl Of Darkness which you have reviewed !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, my fur and whiskers — I do not remember that at all! Ha, clearly showing my age… 🙂

LikeLike

But had you not forgotten, you would not have had the opportunity to deliver what I’ll hereby dub Line of the Week: “the standard Golden Age method of finding a spouse, namely ‘have them suspected of some terrible crime while finding them attractive’ “. I ROARED at that one; made my day. Lord Peter has a lot to answer for.

LikeLike

And Agatha Christie does a nice riff on it in Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, where the guy being saved from the gallows is a drip and doesn’t feel attracted to his savior in the least.

LikeLike

Good post JJ and yes poisoning tales do open themselves up to some bad writing in terms of the how dunnit and who dunnit (so nothing major then). But the first one at least is picked up on early by GAD writers as Knox included in his Decalogue a rule about not using poisons unknown to science. Arthur Upfield arguably plays on this though in Wings Above Diamantina, where a poison is used, but it is only known to the aborigine characters rather than the western doctors.

Also I guessing this post or rather the comments includes your weekly use of ‘oh my furs and whiskers’.

LikeLike

I’ve been seeing a lot about Max Afford lately–your post just confirms that I really need to do something about getting my hands on some of his work. Thanks for another fine post, JJ!

LikeLike

Got a book review coming tomorrow that might be a good place to start, Bev. He’s a lot of fun; not a major name for obvious reasons, but he plays with structure exceedingly well and his characters are interesting enough to support his occasional forays into an odd mixture of straight thrillerdom and sensation fiction. It’s a shame he didn’t write more, in my opinion.

LikeLike

Pingback: #110: The Dead Are Blind (1937) by Max Afford | The Invisible Event

Pingback: #111: The Tuesday Night Bloggers – P.G. Wodehouse Defames the Detective Story in ‘Death at the Excelsior’ (1914) | The Invisible Event