![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I first heard of The Deadly Percheron (1946), John Franklin Bardin’s debut novel of identity and madness, when Anthony Horowitz called it his favourite crime novel in an interview (which I’ve been unable to find, so [citation needed] that for now). And then Kate loved it and Brad loved it and so, with this Penguin reprint newly available, I had to check it out. And, honestly, I don’t see it. It opens well — a man visits a psychiatrist, telling stories of leprechauns who have hired him to perform bafflingly inane tasks — and entertains for the first three chapters, but once the key thrust of the plot is reached it grinds to a halt, and only really comes alive again in a closing monologue that brushes most of the things that don’t make sense under the carpet.

Penguin Books

#1186: A Beginner’s Guide to Breaking and Entering (2024) by Andrew Hunter Murray

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Shirley Ballas. Richard Coles. Susie Dent. Richard Osman. Robert Rinder. These days, if you want to publish a crime novel, it clearly helps to be a UK media personality. And why not? Publishing’s an uncertain business, and an existing following should hopefully convert into sales — good luck to them, I say. Add to the above journalist, podcaster, TV-version-of-his-podcaster Andrew Hunter Murray, whose third novel, A Beginner’s Guide to Breaking and Entering (2024), finds him crossing into the sort of genre territory that captures my attention. And while not perhaps leaning as hard into logical reasoning as I’d prefer, there’s much here to enjoy.

#1185: How Sleek the Woe Appears – My Ten Favourite Golden Age Reprint Covers

As someone who has never taken the time to foster any artistic talent, I’m amazed at the skill of people who design book covers. I even tried to start a regular feature on this blog celebrating such endeavours, but couldn’t get enough people interested to go beyond two posts.

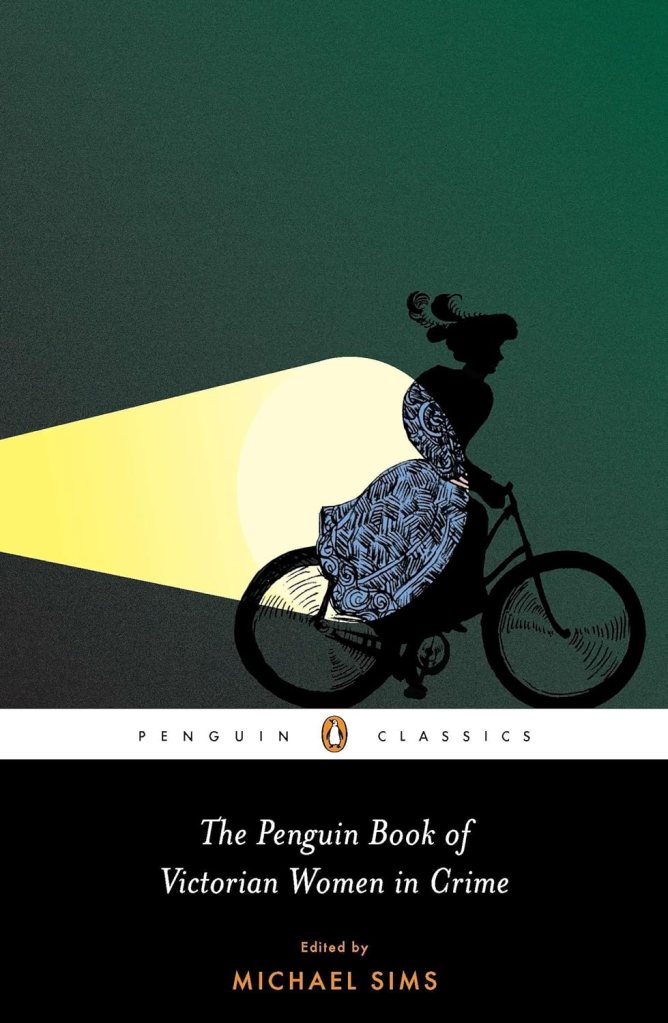

Continue reading#1183: “I have little faith in the analytical powers of the feminine brain…” – The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime [ss] (2011) ed. Michael Sims

Serendipity brought the superb Penguin Book of Gaslight Crime [ss] (2009) edited by Michael Sims to my awareness, and highlighted Sims’ erudition and excellent coverage of Victorian crime fiction, an era of the genre which is holding an increasing fascination for me. And so the opportunity to read another Sims-edited collection was to be seized with alacrity.

Continue reading#1149: Tokyo Express, a.k.a. Points and Lines (1958) by Seichō Matsumoto [trans. Jesse Kirkwood 2022]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let those who lament the — vastly overstated — train fixation of Freeman Wills Crofts take note: Tokyo Express (1958) by Seichō Matsumoto contains so much red-hot timetabling action that I half expected it to be written by someone called Bradshaw. And it’s fitting perhaps that such a small, quiet crime — a double suicide on a gloomy beach — should result in a quiet and low-key investigation, but for me there needs to be a little more to show for all the hours spent looking at the precise movements of trains, ferries, and more. The essential culmination of this is clever, but the route we take to get there could have used a few faster, twistier sections of track.

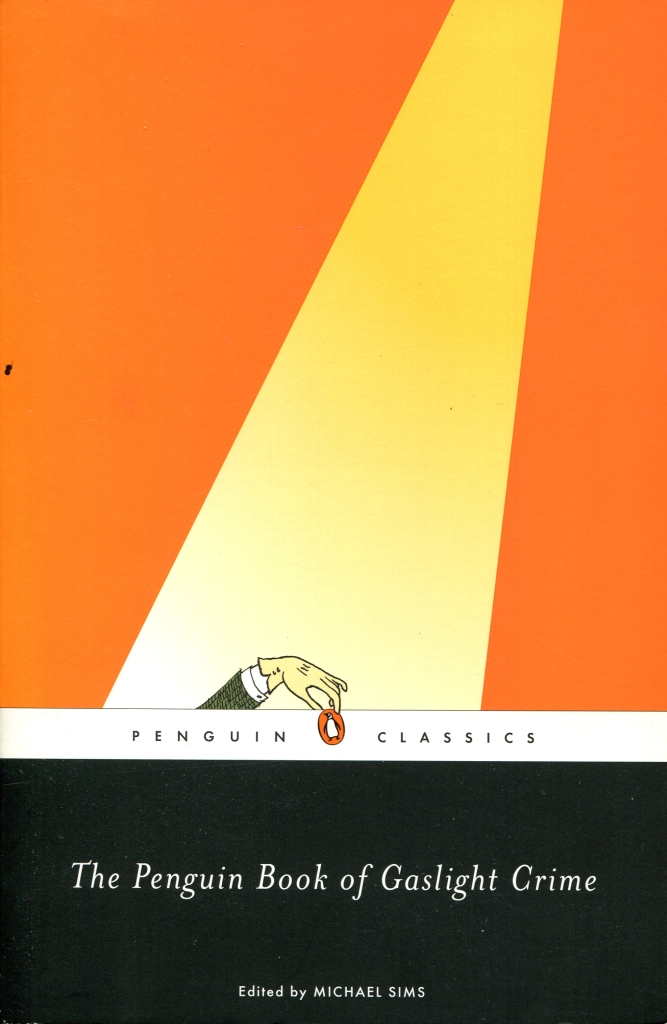

#1077: “A gleeful disregard for law, and an ungentlemanly pride in his own cleverness.” – The Penguin Book of Gaslight Crime [ss] (2009) ed. Michael Sims

Subtitled Con Artists, Burglars, Rogues, and Scoundrels from the Time of Sherlock Holmes, The Penguin Book of Gaslight Crime [ss] (2009) collects twelve stories originally published between 1896 and 1919 — an era which I find myself increasingly interested in, giving birth as it did to the Golden Age of the 1920s-40s.

Continue reading#1068: “I like sometimes to escape from the humdrum of detective investigation…” – The Door with Seven Locks (1926) by Edgar Wallace

A title like The Door with Seven Locks (1926) suggests all manner of locked room excitement, hopefully resulting is some impossible crime shenanigans. So imagine my surprise when this ended up being little more than a straight thriller with some (perhaps not unexpectedly, this is Edgar Wallace after all) weird ideas at its core.

Continue reading#1064: The Case of the Late Pig (1937) by Margery Allingham

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’m in a confusing place with Margery Allingham. I definitely read three of her books when I started getting into Golden Age detective fiction, one of which, I’m almost certain, was The Beckoning Lady (1955) and very hard work indeed. A few years passed, and I next thoroughly enjoyed the amoral ingenuity of Police at the Funeral (1931) before stumbling badly over Flowers for the Judge (1936) and sort of abandoning her, faintly dissatisfied. So when The Case of the Late Pig (1937) passed into my hands, the mere 132 pages of this Penguin edition commended themselves as an opportunity to reacquaint myself with the author and see how things go.

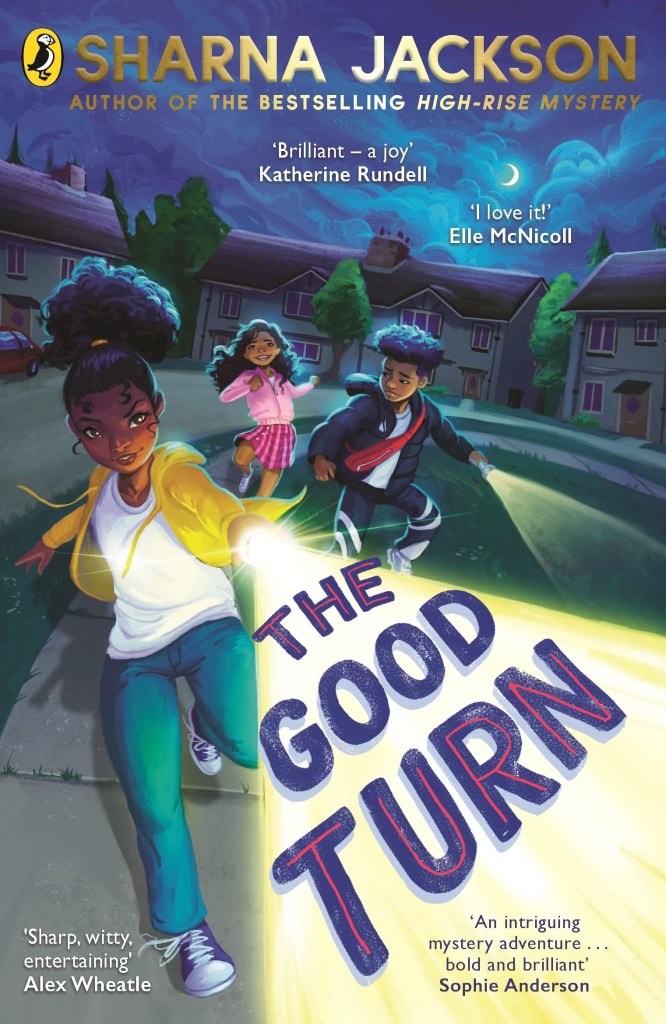

#1042: Minor Felonies – The Good Turn (2022) by Sharna Jackson

Well, it took seven-and-a-half years and over one thousand posts, but it’s finally happened: I have read a book about which I can find nothing to say.

Continue reading#1015: Epitaph for a Spy (1938) by Eric Ambler

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Epitaph for a Spy (1938) places me at the centre of a Venn diagram of two things I heartily dislike — the everyman espionage fiction of John le Carre, and novels whose protagonists cluelessly accidentally their way along — and so I shouldn’t exactly be surprised that these two wrongs have failed to combine to produce something I would enjoy. This story of languages teacher Josef Vadassy strong-armed into helping identify a spy while on holiday at an exclusive French pension is, in fact, riddled with just about every trope and facet of genre fiction that I dislike, and it’s difficult to imagine Eric Ambler’s intent in writing such a book. But, I get ahead of myself…