-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

Last week, I was moved to reflect upon the end of the archetypal Golden Age detective novel, and this week I’m moved to reflect on its beginning. The essential ludic air at the heart of the best of the genre is not quite there in The Duke of York’s Steps, but one can feel the inalienable ingredients of the form straggling into line to give shape to a story that retains fidelity to a type of plot that, at this stage, was understood if not quite mastered. If anything, the mystery feels almost over-subtle — like Antidote to Venom, it seems a trifle unlikely that such a set of circumstances as these would come to warrant criminal investigation — and so approximately the first quarter is spent trying to manufacture the necessary traction for the detection to begin in earnest.

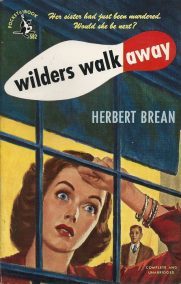

Last week, I was moved to reflect upon the end of the archetypal Golden Age detective novel, and this week I’m moved to reflect on its beginning. The essential ludic air at the heart of the best of the genre is not quite there in The Duke of York’s Steps, but one can feel the inalienable ingredients of the form straggling into line to give shape to a story that retains fidelity to a type of plot that, at this stage, was understood if not quite mastered. If anything, the mystery feels almost over-subtle — like Antidote to Venom, it seems a trifle unlikely that such a set of circumstances as these would come to warrant criminal investigation — and so approximately the first quarter is spent trying to manufacture the necessary traction for the detection to begin in earnest. At some point between 1940 and 1960, puzzle-oriented detective fiction began an inexorable shift into what has now become know as crime fiction, wherein plot machinations took a back seat and character, setting, and ambience became more prevalent. Where detective fiction was mostly interested in the fiendish puzzle, crime fiction was more about the challenge to the status quo, and the effect this has on the people involved. And Wilders Walk Away, Herbert Brean’s debut novel, might just be the perfect peak between the two, because I do not remember having read a puzzle that was so intricately invested in the status quo. What emerges is necessarily a little confused about what it wants to be.

At some point between 1940 and 1960, puzzle-oriented detective fiction began an inexorable shift into what has now become know as crime fiction, wherein plot machinations took a back seat and character, setting, and ambience became more prevalent. Where detective fiction was mostly interested in the fiendish puzzle, crime fiction was more about the challenge to the status quo, and the effect this has on the people involved. And Wilders Walk Away, Herbert Brean’s debut novel, might just be the perfect peak between the two, because I do not remember having read a puzzle that was so intricately invested in the status quo. What emerges is necessarily a little confused about what it wants to be.

When a man is found dead, stabbed between the eyes by a unicorn (of indeterminate nationality) — a, yes, fictional animal that can nevertheless apparently turn invisible at will — you don’t expect to find yourself in the GADU. And when a second victim is then killed in the same way but in full view of witnesses, if one can witness an invisible animal, you better hope you’re in the GADU or else things are about to get silly. Well, it’s your lucky day, because you are in a classic impossible crime mystery and things are about to get silly — this book is probably the final time John Dickson Carr had all the ingredients for a classic and didn’t actually write it, instead leaving a few edges untouched so that the overriding impression is slightly more “Er…what?” than “Hell, yeah!”.

When a man is found dead, stabbed between the eyes by a unicorn (of indeterminate nationality) — a, yes, fictional animal that can nevertheless apparently turn invisible at will — you don’t expect to find yourself in the GADU. And when a second victim is then killed in the same way but in full view of witnesses, if one can witness an invisible animal, you better hope you’re in the GADU or else things are about to get silly. Well, it’s your lucky day, because you are in a classic impossible crime mystery and things are about to get silly — this book is probably the final time John Dickson Carr had all the ingredients for a classic and didn’t actually write it, instead leaving a few edges untouched so that the overriding impression is slightly more “Er…what?” than “Hell, yeah!”.

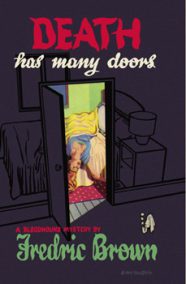

You know the score: a tough-guy PI in a business slump, sitting in his office typing out a letter using one finger (real men don’t type), when in walks a knockout redhead with “everything that should go with red hair”. She needs his help, he’s her last chance. Well of course, sweets, what seems to be the problem? She’s being hunted, y’see, someone wants to kill her. Calm down, baby doll what’s his name? Well, that’s the problem; she’s being hunted by…Martians. It’s a lovely little moment of confounded expectations early on in Brown’s pulpy tale and sets the tone for the number of conventions he refuses to conform to as things progress. And, since he’s far from smug about it, it works very well indeed.

You know the score: a tough-guy PI in a business slump, sitting in his office typing out a letter using one finger (real men don’t type), when in walks a knockout redhead with “everything that should go with red hair”. She needs his help, he’s her last chance. Well of course, sweets, what seems to be the problem? She’s being hunted, y’see, someone wants to kill her. Calm down, baby doll what’s his name? Well, that’s the problem; she’s being hunted by…Martians. It’s a lovely little moment of confounded expectations early on in Brown’s pulpy tale and sets the tone for the number of conventions he refuses to conform to as things progress. And, since he’s far from smug about it, it works very well indeed.