British Library Crime Classics

#140: Death of Jezebel (1948) by Christianna Brand

Apologies for my recent blogging absence; a combination of what I understand are referred to as ‘IRL’ circumstances and the fact that everything I picked up and tried to read was absolute dreck put something of a kibosh on things. The sensible thing seemed to be just to write off September and move on. So now I’m back with the oft-cited classic — and so inevitably hard-to-find outside of the USA, where the lovely Mysterious Press have published it — locked room mystery Death of Jezebel by Christianna Brand. Why this one? Well, it’s supposed to be awesome and I’m trying to get into Brand, having been thoroughly meh’d by Green for Danger (1944) and slightly more taken with Suddenly at His Residence (a.k.a. The Crooked Wreath) (1946). So, how did I fare?

Apologies for my recent blogging absence; a combination of what I understand are referred to as ‘IRL’ circumstances and the fact that everything I picked up and tried to read was absolute dreck put something of a kibosh on things. The sensible thing seemed to be just to write off September and move on. So now I’m back with the oft-cited classic — and so inevitably hard-to-find outside of the USA, where the lovely Mysterious Press have published it — locked room mystery Death of Jezebel by Christianna Brand. Why this one? Well, it’s supposed to be awesome and I’m trying to get into Brand, having been thoroughly meh’d by Green for Danger (1944) and slightly more taken with Suddenly at His Residence (a.k.a. The Crooked Wreath) (1946). So, how did I fare?

Continue reading

#114: Till Death Do Us Part (1944) by John Dickson Carr

People hold weird beliefs: that the moon landings have all been faked, for instance, or that the moon is hollow, or that the phases of the moon have anything at all to do with your love life or finances. Some people might even hold weird beliefs not about the moon. Here’s one: I firmly believe that for the remainder of human history there will never again be anyone who writes the detective novel as well as did John Dickson Carr at his peak. When I eventually narrow my ten favourite detective novels of all time down to a list that is actually ten books long, there’s a real chance all ten of them will be by Carr. And, I’ll tell you now, it will definitely feature The Problem of the Green Capsule, which in my current mood I consider to be the pinnacle of the form.

People hold weird beliefs: that the moon landings have all been faked, for instance, or that the moon is hollow, or that the phases of the moon have anything at all to do with your love life or finances. Some people might even hold weird beliefs not about the moon. Here’s one: I firmly believe that for the remainder of human history there will never again be anyone who writes the detective novel as well as did John Dickson Carr at his peak. When I eventually narrow my ten favourite detective novels of all time down to a list that is actually ten books long, there’s a real chance all ten of them will be by Carr. And, I’ll tell you now, it will definitely feature The Problem of the Green Capsule, which in my current mood I consider to be the pinnacle of the form.

Continue reading

#86: Where has all the classic detective fiction gone…?

If you’re anything like me, well, firstly my condolences, but also you have a list of books not printed any time in the last few decades that you spend hours scouring secondhand bookshops, book fairs, online auction sites, and other people’s houses in the hope of finding. A lot of them – in my case, say, The Stingaree Murders by W. Shepard Pleasants – are rather obscure and so their lack of availability is understandable, but in other cases it just seems…baffling.

Continue reading

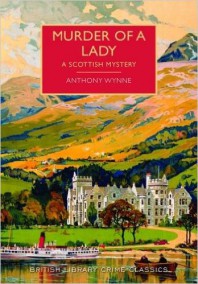

#78: Murder of a Lady (1931) by Anthony Wynne

You’ll be aware by now, I hope, that I’m quite the fan of a locked room murder. That quantal aspect of something that can’t have happened but nevertheless did tickles me greater the more I read, and so the republication of anything from the classic era is always a cause for celebration. The British Library continue their excellent Crime Classics series with this, their first impossible crime, in which elderly spinster Mary Gregor is found dead in her locked and bolted bedroom (a nice touch with the door lock forestalls the prospect of jiggery, and indeed pokery, there) with no sign of a weapon and the blow that killed her containing the scale from a herring and so stirring up superstitious rumours of merman-like ‘swimmers’ finding their way in to dispatch her.

You’ll be aware by now, I hope, that I’m quite the fan of a locked room murder. That quantal aspect of something that can’t have happened but nevertheless did tickles me greater the more I read, and so the republication of anything from the classic era is always a cause for celebration. The British Library continue their excellent Crime Classics series with this, their first impossible crime, in which elderly spinster Mary Gregor is found dead in her locked and bolted bedroom (a nice touch with the door lock forestalls the prospect of jiggery, and indeed pokery, there) with no sign of a weapon and the blow that killed her containing the scale from a herring and so stirring up superstitious rumours of merman-like ‘swimmers’ finding their way in to dispatch her.

On the spot is Dr. Eustace Hailey, who by his reputation appears to be Wynne’s incumbent amateur sleuth, and so he is pulled into a Highland mystery at a gloomy old ancestral home that ends up the scene of plenty of mysterious comings and goings, clandestine meetings, false leads, and several further seemingly-impossible deaths. Obviously we know he’ll solve it in time, but who will be left to act as a suspect as the dramatis personae gets whittled down and down?

Continue reading

#58: The Problem of the Green Capsule, a.k.a. The Black Spectacles (1939) by John Dickson Carr

Marcus Chesney doesn’t have much faith in human observation. To prove his point, he arranges to put on a short demonstration for three witnesses, after which he will ask them questions about what they saw – secure in the knowledge, he says, that they’ll get the answers wrong. The demonstration goes ahead, as part of which a disguised figure enters the room…and poisons Chesney in front of everyone before vanishing. It swiftly becomes apparent that the murderer must not only be responsible for a spate of recent poisonings in the village but must also have somehow been one of only four people. The only problems are that one of them has a rock-solid alibi and the other three were all watching the performance…

Marcus Chesney doesn’t have much faith in human observation. To prove his point, he arranges to put on a short demonstration for three witnesses, after which he will ask them questions about what they saw – secure in the knowledge, he says, that they’ll get the answers wrong. The demonstration goes ahead, as part of which a disguised figure enters the room…and poisons Chesney in front of everyone before vanishing. It swiftly becomes apparent that the murderer must not only be responsible for a spate of recent poisonings in the village but must also have somehow been one of only four people. The only problems are that one of them has a rock-solid alibi and the other three were all watching the performance…

Continue reading

#39: The Hog’s Back Mystery, a.k.a. The Strange Case of Dr. Earle (1933) by Freeman Wills Crofts

There is a branch of Mathematics known as combinatorics which studies the interactions of countably finite discrete sets. Or, in English, it’s the formal study of combining things in all the possible ways they can be combined. It’s a little bit like doing a jigsaw by picking up one piece and then going through the box to try every other piece to find one that fits with that piece, and then going through again to find another piece that fits with those two…and so on until you’ve finished the picture. Approximately a third of the thesis I wrote in my final year of university was based in a combinatorial approach to solving a particular problem (I shall spare you the details), and the formalisation of what sounds like an exceptionally dull way to go about something took on for me a particular beauty in the context of all the mathematics I has studied to that point.

There is a branch of Mathematics known as combinatorics which studies the interactions of countably finite discrete sets. Or, in English, it’s the formal study of combining things in all the possible ways they can be combined. It’s a little bit like doing a jigsaw by picking up one piece and then going through the box to try every other piece to find one that fits with that piece, and then going through again to find another piece that fits with those two…and so on until you’ve finished the picture. Approximately a third of the thesis I wrote in my final year of university was based in a combinatorial approach to solving a particular problem (I shall spare you the details), and the formalisation of what sounds like an exceptionally dull way to go about something took on for me a particular beauty in the context of all the mathematics I has studied to that point.

Continue reading

#26: British Library Crime Classics republishing Murder of a Lady (1931) by Anthony Wynne!

I don’t really do news, but am very excited to learn that one of the forthcoming titles the British Library will be including in its increasingly excellent Crime Classics collection is Anthony Wynne’s 1931 impossible crime novel Murder of a Lady (a.k.a. The Silver Scale Mystery). It’s a locked room of some repute, and has been preposterously hard to find for many a year now – I’ve not read it myself, and so am doubly excited that it’s being brought back. Everyone’s favourite rainforest-named internet retailer has the following synopsis:

Duchlan Castle is a gloomy, forbidding place in the Scottish Highlands. Late one night the body of Mary Gregor, sister of the laird of Duchlan, is found in the castle. She has been stabbed to death in her bedroom – but the room is locked from within and the windows are barred. The only tiny clue to the culprit is a silver fish’s scale, left on the floor next to Mary’s body. Inspector Dundas is dispatched to Duchlan to investigate the case. The Gregor family and their servants are quick – perhaps too quick – to explain that Mary was a kind and charitable woman. Dundas uncovers a more complex truth, and the cruel character of the dead woman continues to pervade the house after her death. Soon further deaths, equally impossible, occur, and the atmosphere grows ever darker. Superstitious locals believe that fish creatures from the nearby waters are responsible; but luckily for Inspector Dundas, the gifted amateur sleuth Eustace Hailey is on the scene, and unravels a more logical solution to this most fiendish of plots.Anthony Wynne wrote some of the best locked-room mysteries from the golden age of British crime fiction.This cunningly plotted novel – one of Wynne’s finest – has never been reprinted since 1931, and is long overdue for rediscovery.

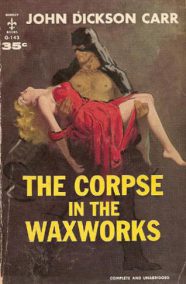

The penultimate case for John Dickson Carr’s first sleuth, Henri Bencolin, opens with a wonderful demonstration of the reputation which that juggernaut of justice enjoys among the less salubrious sections of French society: ‘Bencolin was not wearing his evening clothes, and so they knew that nobody was in danger.’ The palpable sense of relief this engenders in all who see him as he travels from tavern to tavern captures the character with a clarity that shows how much Carr grew as an author over his opening five books, and augurs well for the Fellian delights that would follow soon upon the heels of this as Carr hared his way up the detective fiction firmament and into history. And it sets the scene nicely for a deceptively complex little book that almost feels like a short story in its setup, but is wrought into something more by the expert pacing Carr has honed in the couple of short years since It Walks By Night (1930), showing here his emerging talent for taking a situation that many others would struggle to fill 20 pages with and making every nuance and moment of its 188 pages count.

The penultimate case for John Dickson Carr’s first sleuth, Henri Bencolin, opens with a wonderful demonstration of the reputation which that juggernaut of justice enjoys among the less salubrious sections of French society: ‘Bencolin was not wearing his evening clothes, and so they knew that nobody was in danger.’ The palpable sense of relief this engenders in all who see him as he travels from tavern to tavern captures the character with a clarity that shows how much Carr grew as an author over his opening five books, and augurs well for the Fellian delights that would follow soon upon the heels of this as Carr hared his way up the detective fiction firmament and into history. And it sets the scene nicely for a deceptively complex little book that almost feels like a short story in its setup, but is wrought into something more by the expert pacing Carr has honed in the couple of short years since It Walks By Night (1930), showing here his emerging talent for taking a situation that many others would struggle to fill 20 pages with and making every nuance and moment of its 188 pages count.