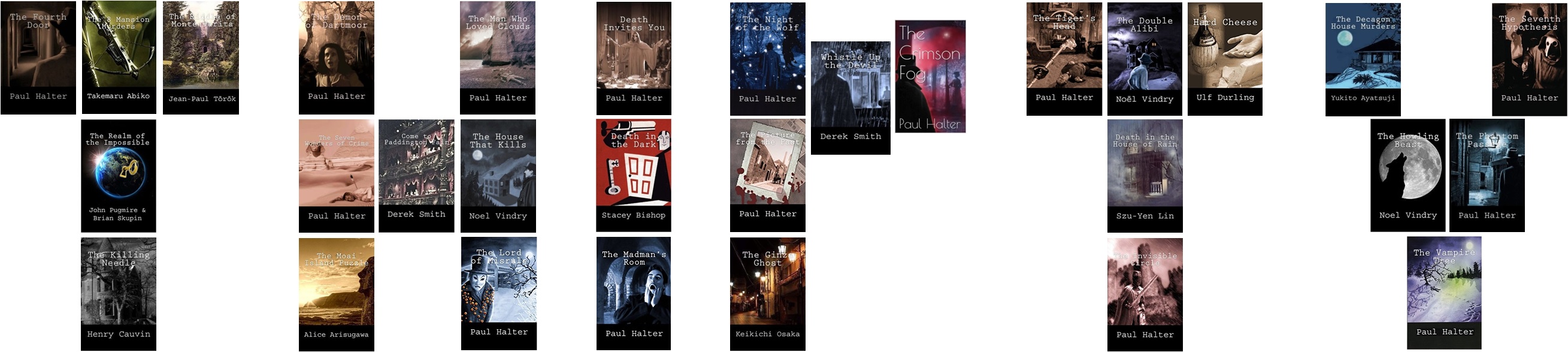

I was saddened to learn of the recent death of John Pugmire who, for the best part of the last 20 years, has been instrumental in bringing the works of foreign authors to Anglophone fans, latterly through his Locked Room International imprint.

Continue readingWhy I love…

#1159: A Reading Round-Up for 2023 + Plans for 2024

I love a round-up post, a chance to reflect on what’s gone in the year before and to look ahead to what the future holds. So, following on from last year’s, here’s my review of bookish things for 2023.

Continue reading#1156: We Barred the Windows and the Doors – My Ten Favourite Impossible Crimes

I’ve been moved of late to give some thought as to what my favourite examples of my favourite subgenre of detective fiction could possibly be. And I’m finally willing to commit — so here are, for today at least, my ten favourite impossible crimes in fiction.

Continue reading#1119: Here a Star, and There a Star – My Ten Favourite Ramble House Novels

It looks like I might be making these ‘Ten Favourite…’ lists a thing, having previously done fictional detectives and British Library reissues; today, we turn our attention to the great work done by Ramble House, publishers of an unusual mix of crime and weird fiction.

Continue reading#1080: Our Splendours Are Menagerie – My Ten Favourite ‘New to Me’ British Library Crime Classics

I looked at my ten favourite fictional sleuths a little while ago, and so, in honour of today’s Bodies from the Library conference at the British Library, here are my ten favourite novels that the excellent British Library Crime Classics range introduced me to.

Continue reading#1044: To Foe of Theirs I’m Deadly Foe… – My Ten Favourite Literary Detectives

Perhaps April Fool’s Day isn’t the best scheduling of this post, but the recent experience of dragging my way through Helen Vardon’s Confession (1922) by R. Austin Freeman got me thinking about the literary detectives I’d follow to hell and back, and I figured that it might be worth expanding upon.

Continue reading#1000: A Locked Room Library – One Hundred Recommended Books

In the back of my mind when I started The Invisible Event was the idea that exactly half of what I’d post about would feature impossible crimes, locked room mysteries, and/or miracle problems — and although this proportion started an irreversible slide after the first 500 or so posts, the impossible crime remains my first love.

Continue reading#594: The Punch and Judy Murders – A Case of Identity in Charade (1963) [Scr. Peter Stone; Dir. Stanley Donen]

Approximately two months ago, Kate at CrossExaminingCrime invited a bunch of bloggers to contribute to a collaborative post on our favourite mystery movies. You can view the results here — without my contribution, because, despite being given plenty of warning, I couldn’t organise myself in time.

Continue reading

#512: Policeman’s Lot – Ranking the Edward Beale Novels of Rupert Penny