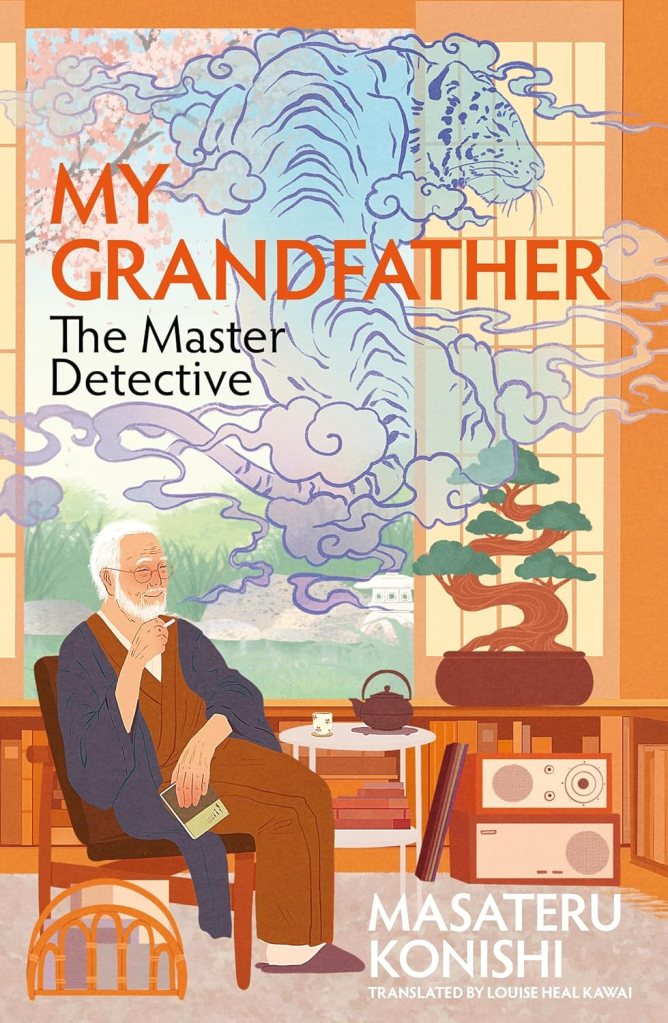

A collection of short stories, each part of an overall arc, My Grandfather, the Master Detective (2023) by Masateru Konishi is yet another intriguing Japanese mystery carried over into English by Louise Heal Kawai for our enjoyment.

Inspired, somewhat heartbreakingly, by the author’s experiences of caring for his dementia-afflicted father, the essential idea here sees 27 year-old teacher Kaede calling in on her grandfather, who has Lewy Body Dementia. One of the many horrors of such a disease is, of course, that you can never be sure in what state you will encounter the sufferer, and Kaede finds it especially tough to see her grandfather’s once sharp mind decline. The man had been, in his younger days, a fan of the greatest form of fiction ever achieved — I speak, of course, of the detective novel — and, alongside noted critic Takeshi Setogawa, would discuss and dissect mysteries for hours.

When Kaede buys a collection of Setogawa’s writing, a minor mystery concerning the book seems to give her grandfather the chance to once again mull over a problem of logic, and Kaede starts to see the old spark of him return. So, as she encounters various other mysteries and hears of inexplicable murders, she brings them to Grandpa’s attention in the hope of providing some fuel for his ailing brain.

All of this is set up in first chapter/story ‘Those Little Scarlet Cells’, so we’ll pass over that — well, there’s little more to add — and take the mystery chapters one by one, given that this is what we’re here for…

First up, ‘The Izakaya Locked-Room Murder Mystery’, which sees a body appear in borderline-impossible circumstances in a crowded restaurant. It’s clear that Konishi wants to explore the principles of care as much as the concepts of mysteries, as there’s a lot of information here that does not bear directly on the case. Not a problem for me, I just mention it because the names invoked in the early stages of the book — John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen — might have some of you set up anticipating a far denser puzzle plot.

There is, of course, a bit of meta-discussion about how old-fashioned English language mysteries are, y’know, out of vogue (“[T]hese classic murder mysteries are an artificial construct to begin with, and translation only adds further layers of artificiality to the story…”), but the puzzle is interesting (though not really a locked room mystery) and Kawai’s translation retains the right mix of the unfamiliar easily explained:

“You remember that izakaya we went to about a year back? Haruno, on the north side of Himonya?”

“Yes, of course I remember.”

How could she forget? Back then, that little neighbourhood bar was her grandfather’s favourite haunt, and Kaede had picked it because she knew she’d feel uncomfortable drinking alone with Iwata

A couple of nice little moments lift this above the common — though I’m not convinced that (rot13) fbzrbar pbhyq pbashfr ehoovat lbhe arpx jvgu phccvat lbhe puva va bar unaq — and the eventual answer is nicely reached by our housebound septuagenarian.

In a manner that aptly reflects A Graveyard to Let (1949) by Carter Dickson — surely a better reference than The Curse of the Bronze Lamp (1945), which Konishi chooses — ‘The Vanishing Person at the Pool’ concerns an attractive primary school teacher who dives into the school pool after a lesson and disappears. I like the original solution to this, because the second solution doesn’t account for a key element, since (rot13) gurl pbhyqa’g xabj gur obl jbhyq whzc vagb gur cbby…and so how were the latter stages of the plan supposed to work?

Still, there’s a lovely moment of assumption which is undeniably well-prepared and would pass as a breathlessly subtle clue in a more formal novel of detection, so the story is not without its high spots, not least that haiku.

Elsewhere, Kaede’s growing romance with either her colleague Iwata or his school friend Shiki continues to build, but of more interest is the hints of something sinister with regard to her mother:

[Kaede] wondered when it was that she’d started to fear getting close to people.

Well, it must have been back then — after learning what had happened to her mother. Since then, it hadn’t only been romantic relationships she’d avoided, but even just meeting people, forming close friendships. That old unhealable wound…

The plot, it acquires the thickness.

I’ve heard it said that editors try to bury the less good stories in a collection in the middle, and that’s certainly borne out with ‘They Were Thirty-Three!’. A room of young students practising English, a voice from an unattributable source…no, I’m not buying this. The use of the era-appropriate details is good — you couldn’t have written this in 2019, let’s say — especially how they get folded in without you really thinking about it, but as a mystery this is rather weaker than what has come before.

A title like ‘The Phantom Lady’ veers into Cornell Woolrich territory, and, indeed, reference is made to that tale and to Cabin B-13 (1943) by John Dickson Carr. The problem this time around sees Iwata out for a run when he comes across a middle-aged man and a teenager engaged in some kind of skirmish. Intervening, he chases the older man away, only to discover that the teen has been stabbed and is bleeding heavily. As a woman he passes every week on this run approaches, Iwata asks her if she saw everything, and she nods…and then turns and walks away, leaving Iwata to be arrested by a passing policeman.

Shiki and Kaede take up the case: if they can find the woman, they might have a witness who can attest to Iwata’s innocence. And yet, no-one they speak to along the route remembers her or her distinctive power walking gait. Can Kaede’s grandfather shed any light on the encounter, and suggest where this woman might be found?

There are some nice touches to this, but the core mystery isn’t too hard to fathom, and it’s guilty of some remarkably convenient reasoning to wrap things up quickly. And it feels a little awkward the way the mystery is book-ended beforehand by a clumsy reference that’s going to come into play next, and afterwards by spelling out the meaning behind Kaede’s cryptic references to her mother. This is the slightest mystery so far, and you really feel it.

The invoking of Woolrich earlier turns out to be fitting, since ‘The Riddle of the Stalker’ could almost be a Woolrich story, being much longer on suspense than it is on a series of — it must be said, extremely wonky — deductions before, after pages and pages of Ellery Queen-calibre reasoning (and, no, I don’t mean that as a compliment) reaching a shocking conclusion that’s been signposted for about 150 pages. It’s a testament to the translation that I found myself caught up as I did despite my hind-brain being rather bored by the creakingly slow development of the plot herein, and it’s a shame not to finish on a stronger story, but Konishi deserves credit for applying himself to a range of subgenres here, even if it’s not quite what I was expecting.

Obviously publishers who aren’t Pushkin Vertigo are allowed to put out Japanese mysteries — indeed, please, publishers, do put out Japanese mysteries, and get the talented and increasingly genre-savvy Kawai, Bryan Karetnyk, Jesse Kirkwood, Jim Rion, and Ho-Ling Wong to translate them — but it’s to be wondered if this one was selected by Macmillan because it falls between a few stools and so is theoretically likely to have a wider appeal: it’s sort of a romance, it’s sort of about family, it’s a little bit of a Life in Modern Japan novel, and it has some mysteries in it — mysteries with references to the classics authors names above and some others besides.

I naturally come to it for the last of those qualities and, while I enjoyed many of the trappings of a classic-era mystery — the diagrams, the simply-parsed problems that give rise to unseen complications, some of the clever oversights you’re encouraged into — I’m not entirely sure I can rave about this as a collection of mysteries, because of that split focus. Of course, the joy of books is that we all respond differently and you might well adore the very things that slightly disappointed me here, so it is worth checking out of you suspect this sort of thing might be to your liking — for its sheer differentness if nothing else.

In the plus column, I read it very quickly, aided no doubt by another superb translation by Kawai, and the central relationships, while a little under-developed, are difficult not to like. It’s pleasing to see the genre expanding out in these ways — the last thing we want is a hidebound exploration of supposed rules and tropes that very few people seem to understand any more — and one of the things I really enjoy about this genre is how diversely it can be applied to so many different story patterns. Any alternative perspectives on the above, then, are actively encouraged.