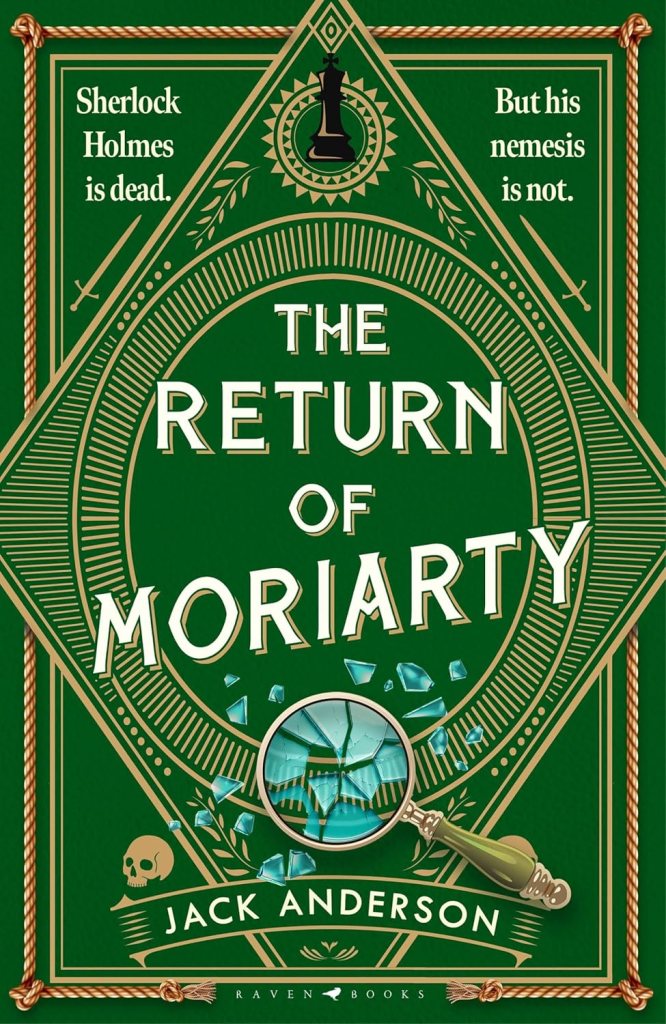

Donning my waders to enter the fetid waters of Sherlock Holmes pastichery, I was prepared to kiss a lot of frogs on the way to a prince or two. But with The Return of Moriarty (2025) by Jack Anderson I’ve stumbled over a very handsome prince indeed far sooner than I’d ever hope — put simply, it’s wonderful, and if you’re a fan of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes universe then you need a copy of this book in your life.

We open with the diary of Dr. Francisco Castillo from 5th May 1891 as he, in a secluded cabin some 10 miles from the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland, waits for the arrival of the person who has hired him to, apparently, provide care to someone suffering an undisclosed illness. Before long, two men show up on his doorstep: one “a menacing figure approaching six foot in height, his exposed forearms displaying a lithe frame of tightly bound muscle” and the other on the verge of death:

While the two are of a similar height, the injured figure seems to lack his companion’s efficient musculature. His head is covered by a black burlap sack. His clothes are damp, his thin limbs shivering, his white undershirt blossoming with blood. Every visible patch of skin is either red-raw with ice burn or smudged with inky purple bruises.

Over the coming days, Castillo will tend to this anonymous, injured man, under the never-slackening scrutiny of the other, slowly bringing the former back to health. And yet, there is already a serpent in the garden, since before the men arrived Castillo took delivery of two letters — one for him, and the other, his own missive states, for the injured man who has arrived — which cast these men in the most suspicious of lights. Indeed, Castillo finds himself thinking that, if the letter sent simply “To the Doctor” had even the slightest element of truth about it, then perhaps it might be better for everyone if the injured man never recovered from his injuries…

It’s one of the book’s key triumphs that the meta-textual element here — you know who the injured man is, because you’ve read the title of the novel — never intrudes on the story being told. I was intrigued to see where Anderson would go with this, and the answer is that on page 37, in a transcript of a recording made by Miss Helga Linse, he does what might be one of the most genius things ever done in a Sherlock Holmes story. It would honestly not be possible to overstate how blown away I was by the intelligence behind this tiny moment in the story overall, and it was at this point that I started to suspect that we had something rather special on our hands.

From here, and for the majority of the rest of the book, we jump to the diary of Clara Mendel, recalled to Schloss Alber, the ancestral home of the Alber family in Bavaria, which perches on a mountainous ledge high above the nearest town. It was here that Clara grew up after her commoner mother married eldest son Alexander, and as such she was both a member of the family and an outcast. Family in-fighting has reached a point where Alexander’s tomb — he died tragically in a fire several years before — is due to be reopened as part of the legal challenges surrounding an heirloom originally buried with him, and Clara has been recalled by Lord Alber to be present for the event. And so she returns to a house that contains for her many ghosts, confronting not just the family and their multi-faceted responses to her presence, but also Hugo Strahm, a guest of Lord Alber’s.

Of the plot from this point I’ll try to say as little as possible. No mystery is made about how this story represents a Return where Professor James Moriarty is concerned, but the way Anderson chooses to tell this from the perspective of people who are ignorant of the titanic struggle between Holmes and Moriarty really allows the story to breathe. As Clara begins to involve herself more in the events of Schloss Alber, and as more of her own story emerges, this begins to feel like a novel in its own right, not just a story where you’re expected to go ‘Squeeeeee…!’ when our evil mathematician hoves into view.

And, again, this is where the meta-textual aspect of Anderson’s telling is so clever. The story is compelling enough without the presence of the Napoleon of Crime, since Clara has much in the way of past relations with these people to navigate, and the way each of the Alber children come to feature is remarkably clear-sighted. There’s one sentence summing up the attitude of elder daughter Margarethe which knocked me back on my heels, so perfectly does it encapsulate everything about her — indeed, in a less accomplished novel that single sentence would be rich enough to contain almost an entire plot of its own. It would be shortlisted for the Booker Prize. People would fawn. Instead it’s a throwaway line here, filling out beautifully a detail this story does not need yet becomes all the richer for containing.

At the core of the book, however, is Clara’s repeated encounters, and growing fascination, with Strahm:

To the other residents of Schloss Alber, Mr. Strahm seems calm as a lake. However, I’ve begun to sense a mild desire on his part to guide me, step by step, into the depths of his identity.

Not only is her vocation simply perfect — how could she be anything else? — she also brings an intelligence (“Twelve of these sixteen squares are the same.”) that is going to capture his interest. And Strahm is equally of interest to Clara because of how different he is to the residents of Schloss Alber (“I can’t tell if I am tethering myself to a man of incredible skill or simply unmatched hubris.”). And yet for all their relationship “undulat[ing] between cooperation and mutual dislike” there is undoubtedly something which draws them to each other — something not unlike penance which sees them both tread a risky line not simply for the thrill of it but almost to spite the other. Indeed, one set-piece towards the middle of the book is to be highly commended for how much it reveals about the two of them both separately and in consort. And it’s all the more brilliant because the deus ex machina is there if Anderson wants to use it, and he swats it aside and does something far, far more interesting.

It’s clear that Schloss Alber has faced an arduous night of its own and that, in returning, I have merely traded one theatre of chaos for another.

The book is also, no spoiler I trust, about the remaking of Moriarty, and one doesn’t simply overturn one of fiction’s great villains in the space of five pages and expect it to stick. The games within games are seemingly endless (“You suspected I would recognise it and confront you…”), with the ever-shifting loyalties and motivations clear without the need to narrate pages of info to the reader. As an examination of the anti-hero, including giving him a solid reason for that status, this is honestly close to perfect: no sudden, big last-minute reversal because he can’t bear to leave the children to drown in the well; instead, a subtle, ever-shifting allegiance that you understand is questing, always questing, for the angle that works for his own conflicted and at times compromised perspective.

More than anything, the Moriarty here feels like Doyle’s Moriarty, just as the patient telling and wonderful character notes feel like something from the Doyle universe. And to find something to do with the character that really does extend his possibilities, and to work in such a note-perfect realisation of Holmes and Dr. John Watson without them ever becoming more than the footnotes they’re intended to be, is a masterstroke that only goes to enhance this book in my estimations. Given the Doyle estate’s willingness to adopt Holmes and Moriarty (2024) by Gareth Rubin as an official entry in the canon, you wonder if they’re kicking themselves now that they didn’t wait twelve months and sign up to Anderson’s take instead. Not that Rubin’s book is bad — it, too, finds something new and interesting to do, as my review above attests — but Anderson’s is better than every Holmes pastiche I’ve yet encountered.

Lest you suspect I have entirely deserted my critical faculties, let me assure you that imperfections exist — for all the narrative devices employed (diaries, a note to a concierge, letters between lovers, etc. etc.) it must be said that the narrative voice of these wildly diverse people barely fluctuates, and Moriarty himself positively rebounds in a matter of days from injuries that would incapacitate someone half his age for months if not years — but the core of the book is unaffected by them, and the little filigree’d touches (c.f., the early game of Find the Lady, the borderline-impossible death from a fall) fill this out in a way that charms, disarms, and feels entirely right.

Anderson also betters the likes of Rubin, Anthony Horowitz, and others in that the closing stages of his novel show a grand design that must surely raise this in the estimation of even the most jaded reader. Sure, not everyone is going to come away from this with the same enthusiasm I feel — Colonel Sebastian Moran deserves better, you may say — but for my money nothing has come this close to looking into the abyss of James Moriarty and reacted so brilliantly when the abyss looked back into them. It deserves to sell in the millions, and I want another ten of them right now. Do yourself, or the Holmes fan in your life, a favour, and get this — in these crowded fields, something very special has just announced itself, and we really should pay attention.

~

You can hear more from Jack Anderson about the writing of The Return of Moriarty in the most recent episode of my In GAD We Trust podcast, here.

Thank you for your recommendation of this wonderful novel. I quickly went to the library and procured this delightful work. I truly enjoyed the style and content. I clearly was not up to the task in realizing who was behind the thief of the sword and all of the back story.

I eagerly await a follow-up with this exciting duo!

LikeLike

I’m delighted to think that I directed someone to this and they had as good a time with it as I did. Wonderful news, I’m so pleased you enjoyed it. And yes, now the long wait for the next book begins…!

LikeLike