Given the state of limerence in which I exist when it comes to the impossible crime in fiction, it was with great excitement that I received a copy About the Murder of the Circus Queen (1932) by Anthony Abbot, which has not one but two entries in Adey.

It is Tod Robinson, manager of Dawson and Robinson’s Combined Greatest Shows on Earth, who first brings the problems facing his circus, due to open that evening at New York’s Madison Square Garden, to the attention of Police Commissioner Thatcher Colt. A variety of incidents — accidents, deaths of animals, damage to expensive equipment — have plagued the company of late, now capped by various performers receiving anonymous notes promising that they will be killed if they perform certain eye-catching tricks at the show on its opening night. Colt and his assistant Anthony Abbot are invited to attend, and, wouldn’t you know it, aerial sensation Josie LaTour is somehow compromised during her act and plummets the full height of the Gardens to the floor, dying instantly.

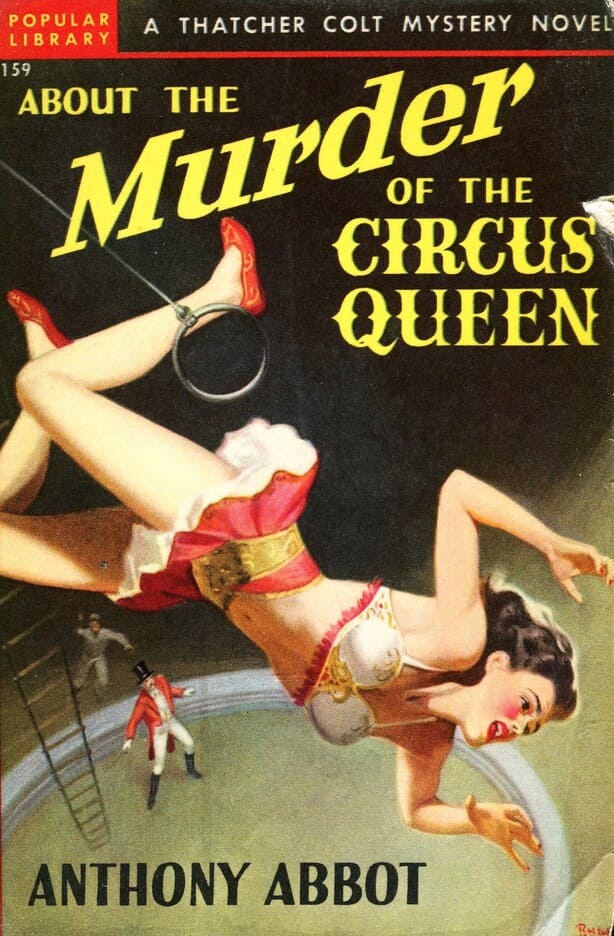

I mean, you’ve read the title and seen the cover of the book, so I don’t consider that a spoiler.

Abbot — the author, this being the nom de plume of Charles Fulton Oursler — is clearly taking the lead from S.S. van Dine, acting as a character in the novel who traipses around after the sleuth and makes ominous presentiments (“I did not guess that within the last few minutes we had been very near a murderer, even then preparing to strike.”) but otherwise no sort of presence at all, making the choice of first-person perspective all the weirder. And Colt is very much in the Philo Vance vein…

…this esthete, who in the seldom privacy of his life was an amateur poet, practising the difficult forms of sonnet and villanelle, this exquisite who in solitude played the flute…

…except that Oursler forgot to give him any sort of personality, preferring him to just be a variety of hobbies we’re told about but never see (he’s also handy in a fight, lest you think him too effete) and then just have a cipher bearing the name Thatcher Colt move from room to room knowing things and being generally dull and difficult to engage with. Say what you like about Vance’s affected manner, and many have, but at least there’s a sense of fun about him; Colt seems to know he’s a copy and so distinguishes himself by being now fun at all.

Once you realise this, you realise that the entire cast suffers from the same problem: everyone is a name linked to a variety of actions, and it becomes increasingly difficult to tell them apart (not helped by three characters called Flandrin, Flandra, and Flandreau). Once the murder is out of the way, and Colt’s convinced that it’s murder very quickly, via a deduction not shared with the reader for a frustrating number of pages, it starts to take on echoes, horror of horrors, of The Roman Hat Mystery (1929), the debut of Ellery Queen that continues to frustrate and underwhelm many people who then pretend they found it enjoyable to this day.

Interview, interview, interview, declaim, declaim, declaim. It gets a little grinding and monotonous, and is only relieved when we finally escape the circus and find indications of more shenanigans elsewhere, with a fight having apparently broken out in a sealed apartment, Oursler laying on some good atmospherics:

Through neat rooms now upturned in a sinister tableau of arrested wrath, we walked as men walk among the ruins of a natural disaster.

The painstaking, almost Humdrum approach Colt takes over his investigations is to be applauded (“He was simply following the one technique in which he reposed a faith that was almost religious — patience, industry, perseverance, the method of endlessly searching for the one vital and revealing clue.”), but it did not, I’m afraid, make for gripping reading where this reader was concerned. It takes place over one night, but I’m not sure that this much talking can fit into the time frame Oursler gives it, unless everyone was coked up and operating at three times normal speed.

And, yes, those impossibilities: hmmm. Adey considers the failure of LaTour’s act to be the first such impossible occurrence, but there’s really no reason why it can’t just be human error or explained away by simple means — she’s not infallible, after all, no matter how spectacular she may be at her job. And he considers the second one to be the dead body found in that ransacked apartment, the door sealed on the inside, except that Colt and Abbot find an open window almost immediately and the first thing they suggest to each other is a possible explanation of how the locking of the bolt from inside with no evidence of anyone left behind could be achieved (and, as far as I can remember, they never go back on this — but the fact that an explanation is immediately apparent to them, like, stops this being impossible, no?). And that’s before they’ve even found the body, so the intrigue here is severely limited.

It is, though, not all bad; though there is one badness to which we must return.

In the book’s credit column, the circus milieu is well-drawn, with a clear reason for why these folk might close ranks on an outside investigation. The “psychic wall separating from show-folk from [the investigators]” is more than just closing ranks, but also “no more than natural [as] in recent years the circus world had labored to establish public confidence. Its standards lifted, it became an honorable institution in American amusement life” and there’s a clear desire to protect this newfound legitimacy. There is, too, a sort of burgeoning resentment at the way they seem to be treated as less than people — evinced no more clearly than billionaire Marburg Lovell’s pursuit of the married Josie LaTour:

How did the banker hope to tempt the lovely Josie? Flatter her — a king of Wall Street wooing a woman of the circus? Or did he stake his desire on the jingle of his money-bags?

And if we’re going to get into these folks being treated as less than human, well, unfortunately we have to talk about the Ubangi tribe, who have been, er, brought over from Africa to act as sideshow attractions amidst the pageantry.

Oh, god, look, there’s no merit in dwelling on this, but it will surprise no-one that Oursler does a less than watertight job of presenting those of another culture entirely sympathetically. True, Josie LaTour herself is said to have expressed the opinion that the circus should have moved on from displaying the tribesmen and -women — with “great wooden rings in the women’s mouths…intended to make their faces hideous, thus discouraging women stealers from other stronger tribes” and described as “duck-billed and disc-lipped…like bloated monstrosities from some old book on demonology” — as sideshow attractions, but they’re mostly kept quiet, brooding, unhelpful, and ruled over by a wild-eyed witch doctor who dresses in elaborate suits and rolls his eyes a lot when he talks. It’s not a thoughtful portrait of an unfamiliar people, alas.

Also, we’re told that the witch doctor can accurately “throw a two-pronged knife some two-hundred yards”. Two-hundred yards?!! Dude should be in the Olympics, not the circus. And I could go on about the many weirdnesses: Josie LaTour has a tendency to whip people with a crop (including the Ubangi) when she gets angry, the police legitimately arrest someone and beat him until he confesses, we’re told the motive is “unique [and] heartlessly cruel” but it’s actually pretty bland…I could go on, but you get the idea. This promised much, and, for me at least, failed to deliver.

About the Murder of the Circus Queen is, then, very much a product of its time in more ways than one: leaning very heavily into the popularity of Van Dine, demonstrating the American lack of facility with the Humdrum plot — c’mon, they’re pretty much always terrible when they try it — and answering its central question with a reveal so unstartling that I honestly had no idea which of the wigs spouting dialogue was the killer when we were brought in on it. I think I’m happy, on this evidence and About the Murder of a Startled Lady (1935) to put Oursler/Abbot down as a very minor player in the great game of GAD — don’t get me wrong, I’d always rather read a book and know I don’t like it than spend my whole life wondering if it’s amazing, but having fooled me twice, and with so many other enticing names on my list, I think I’ll move on without any regrets.

I want to recommend About the Murder of the Night Club Lady as Abbot’s best Thatcher Colt novel, but maybe the Van Dine-Queen School just isn’t for you? At least not those leaning heavily into Van Dine’s popularity (or Ellery Queen). So perhaps you’ll find Clyde B. Clason and Harriette Ashbrook’s takes on the Van Dinean detective story more palatable.

LikeLike

I’ll certainly keep an eye out for Night Club Lady, but Abbot’s all but vanished and I don’t fancy my chances of finding it soon.

Appreciate the other names to check out. I wish I knew why Van Done appeals to me but Queen doesn’t, or why I can’t find anyone to do Humdrummery to match Freeman Wills Crofts. These mysteries will keep me going for a few years yet, so any and all exploration is to be embraced.

LikeLike

I managed to get a nice vintage copy of this with the cover that you have pictured. A very nice physical book. I haven’t been looking forward to reading it though given that I share your impression of Abbot after reading Startled Lady. It sounds like I don’t need to rush to confirm that.

LikeLike

Other comments online seem to place this as about the best of Abbot’s novels, but, equally, we know how much opinions can vary. Can’t say I’d rush back to read more buy him, but maybe I’ll feel curious again in a couple of years,

LikeLike