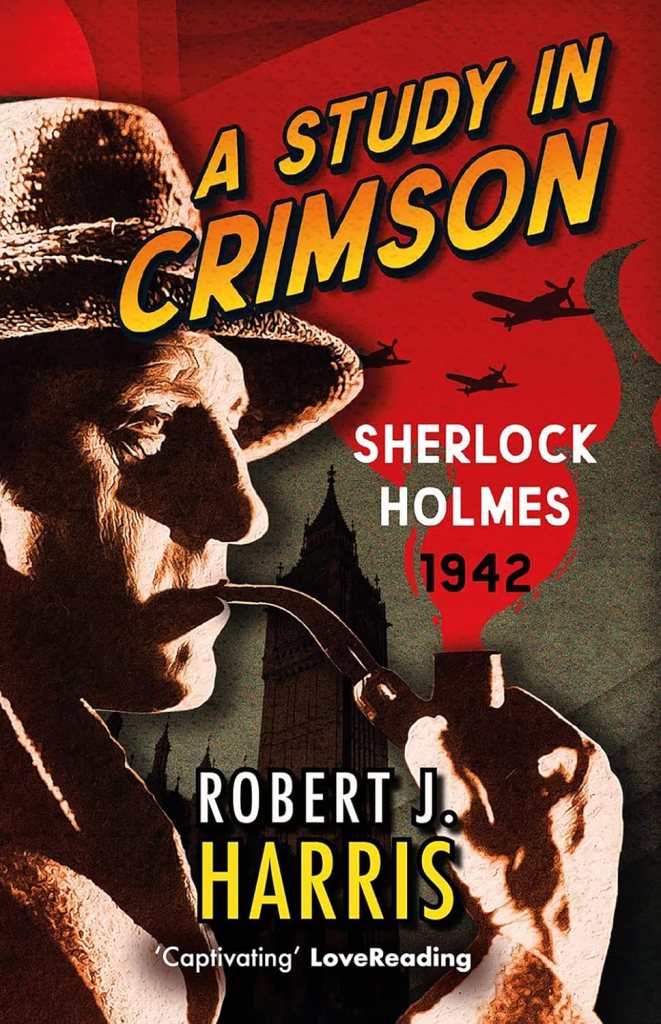

I’m not quite the target audience for a Sherlock Holmes pastiche taking its motivation not from Arthur Conan Doyle’s original canon but instead the 20th Century Fox films and subsequent radio serial starring Basil Rathbone — being as I’ve neither seen nor heard them — but the notion intrigued me enough to give A Study in Crimson (2020) by Robert J. Harris a go.

Harris’s novel, then, posits a world in which Holmes and Watson have “survived into [their] fifties in sufficient health to still be of service to [their] country”, and where, since the outbreak of the Second World War, “Holmes’s time was occupied less and less with private cases and increasingly with urgent calls from [the] beleaguered government”.

The novel starts off with a pleasant little sojourn which is practically a short story in its own right, with the apparently-impossible vanishing of a scientist from a government complex in Scotland seeing the Great Detective called in to clarify the matter. Not only does this give the reader a chance to orient themselves in the correct era, it provides a very pleasant window on the versions of the characters that we’re getting, with Holmes once again drawing much inference from seemingly-obscure clues and Watson, of course, unable to keep up.

Not for the first time I was provoked by my friend’s habitual reticence. “You wouldn’t care to elucidate now?”

“My dear fellow,” he said, closing the door, “I already have.”

The mechanics of the vanishing are far from new, but this hors d’oeuvre before the main course is delightful, with Holmes in almost impish form for a man of his years, and the clever way he sees the solution clearly communicating that, while this may be an older detective then we’re used to, his mental faculties are undiminished. Indeed, this opening 30-page tale is so good that it almost had me hoping that I’d misunderstood the contents of the book and we were getting a collection of short stories.

Back in London, the novel proper begins, when the butchered body of a prostitute — on the anniversary of the first killing by Jack the Ripper — and the legend CRIMSON JACK scrawled on a wall nearby raises the possibility of a new Ripper on the prowl. Given the brutal nature of the crime, and the hints of madness implied in such savagery, Watson has his misgivings about calling Holmes in:

I could not help but feel that if the current killer was as mad as the original Ripper was generally deemed to be, then my friend’s method of rational analysis might not be a sufficient instrument to probe his sick motivations.

Plot-wise, then, A Study in Crimson progresses in very much the fashion you’d expect. Additional bodies pile up on the anticipated dates, including two on the anniversary of the night when it is generally understood the Ripper was interrupted in his first killing and so claimed another victim later on. Various people approach Holmes to help or hinder, including the newspaper man Charlie Deeds, who whips the febrile press into a frenzy as he worms his way closer to the details the police have withheld, and American reporter Gail Preston, who seems to have been introduced to fulfil the sort of role Katharine Hepburn excelled at in the likes of The Philadelphia Story (1940) and proves a canny addition in both reinforcing the era and backing up the theme suggested for the new killer’s motive:

“Could it be that [the killings are] so brutal because they’re a warning to women to keep in their place? You may have noticed that there are a lot of women doing men’s work now, from munitions to flying aeroplanes. Some guys feel threatened by that.”

As a novel of character and era, and especially how the latter shaped much of the former, A Study in Crimson is superb. From police pathologist Leonard King, slowly losing his mind as he dissects the bodies of women and children torn apart by bombs from air raids (“…for long, dreadful months bombs had fallen like rain from the sky, the detonations as relentless as thunder and the raging fires more ruinous than lightning.”) to a nameless bomber crew out for a good time despite the threat of a murderer lurking the streets (“If even half of them are still alive when this dust-up’s over, it’ll be some kind of miracle.”). Harris really does display quite considerable skill in this regard, to the extent that before I was even halfway through I’d already determined to read his second Holmes pastiche, The Devil’s Blaze (2022).

Within the existing Holmes universe, or as much of it as he has to work with, Harris also does solid work: see Tommy Wiggins, excluded from war work on health grounds and so worshipping the ground Holmes walks on for the value his occasional aid is able to provide, or even elder Holmes Mycroft, this really feeling to me like the first time that someone outside of Arthur Conan Doyle’s canon has really got the fractious relationship the brothers must surely have had right (“I could almost fancy that, if I were rash enough to intervene, the very air itself might shatter.”). Harris even repurposes a key element of A Study in Scarlet (1887) neatly, making it a part of Holmes’s story rather than the villain’s, and exposing much of Sherlock’s past in a way that has never been done before so explicitly in my experience of these pastiches.

Crucially, too, it feels — and, remember, I’ve not seen the films or heard the radio plays that gave birth to this novel — like Harris gets Holmes and Watson right. There’s something nicely human about Watson admitting that “I had acquired the somewhat more rounded contours typical of middle age” and voicing his suspicions that Holmes has taken to dying his hair (“It served his vanity well that he was famously a master of disguise.”). The updating of their milieu lends itself to this slightly more human approach to the characters — such speculation would be apostasy in a Victorian-era pastiche — and it’s perhaps fitting that Harris provides an update on Watson’s ever-mobile bullet wound by informing us that “I was shot in both legs by a German machine-gunner” in the First World War. Maybe this was covered in the Rathbone-Bruce films, but Watson being less of a comical figure here implies, to this reader at least, that Harris’s inspiration is loose enough not to feel hidebound by whatever those cases laid out for us.

Which is not to say that the plot lacks cleverness — the various interpretations given to the taunting note Holmes receives are clever — but more, I suppose, to highlight that for me the skill Harris displays is so strong with setting and people that the plot’s various machinations are always going to come second when I think of this book in future (if you can’t spot the killer at their first appearance, for instance, then, well, maybe I can interest you in purchasing one of the many bridges I own in several European capital cities…). I’m writing this review a week after reading the book, for instance, and I cannot for the life of me remember what the motivation for the killings, or their styling after Jack the Ripper, was. I mean, I remember what I was expecting it to be, but I have a feeling it came out a little blander than that and…well, that’s fine — I’m often vague on motive after I finish a book, in fairness, and I was having so much fun with the various successful elements of this that I’d be lying if I said this gap in my memory in any way spoils it.

A Study in Crimson come recommended for anyone willing to explore the Holmes pastiche beyond its usual bounds, and fans of impossible crimes can enjoy the two apparently undoable situations herein (the second being deduced by the Holmes brothers in response to newspaper reports — a very clever idea, well-utilised). Sign me up for whatever other work Harris produces in this universe in future, and many thanks to commenter mvblaze who put me onto to this in the first place.

Hang on a bit – how can they be in their 50s in the 1940s? 80s sounds more possible… or did I miss something? Or do we mean the age they have in the Rathbone and Bruce films? In which case, you don’t mean the Fox films, which are set in the Victorian era, but the ones made by Universal, which transposed the duo to WW2. The most generally liked in those is THE SCARLET CLAW by the way … I profiled the WW2 films, all 12 of them, at Fedora:

(https://bloodymurder.wordpress.com/sherlock-holmes-at-universal-studios/)

LikeLike

And I ranked all the Rathbone/Bruce films – with the help of two friends whose names escape me – here:

https://ahsweetmystery.com/2024/01/05/the-rathbone-bruce-sherlock-holmes-super-draft/

Jim, I hope someday you can watch the best of these – not to review them because I can understand a Sherlockian cringing at the portrayal of Dr. Watson (although I LOVE Nigel Bruce in the role, it’s largely because I grew up with him) but because they were really fun. The Scarlet Claw is a terrific serial killer film, and . . . well, you can see how we ranked them. And the two Fox films set in the Victorian era are actually quite good!

LikeLike

One of these days, maybe; too many books to read in the meantime…

LikeLike

All I know is what Harris says in the opening preface: these are inspired by the 20th Century Fox films, which I’ve not seen. So…maybe they met The Doctor along the way?! 🙂

LikeLike

On a somewhat related note, Nicholas Meyer, well known for many Sherlock pastiches stretching back to the 1970s, has a new book about Holmes and Watson being involved in World War One.

The book tries to hold on to the ‘canon’ and so presents the detectives as in their late sixties.

The story plays off a LOT of actual people and events involved in the war at that time, presented in a GREAT DEAL of detail.

I found almost nothing about this book that could be called a mystery story. It lands almost completely into the espionage /spy /thriller genres. It’s called Sherlock Holmes and The Telegram From Hell and is very well written, with compelling versions of the characters, but not what I was expecting.

LikeLike

Sounds like a lot of fun! I’m only scratching the surface of pastiches at the moment — I’ve not even read Meyer’s Seven Per Cent Solution — but that’s certainly one to put on the list. Thanks for bringing it to my attention

LikeLike

I remember having a pretty good time with this one too. It certainly captured what I like about the Rathbone WWII-era stories!

LikeLike

I’m very intrigued to see how The Devil’s Blaze compares. And to see if Harris writes any more, since at present these are the only two Holmes pastiches attributed to him.

LikeLike

I am curious to read it, too. I haven’t heard talk of a third, but the author is still active and has recently written a Richard Hannay continuation so there’s hope!

LikeLike

What a great review…I’m so pleased you enjoyed this as much as I did.

I thought the second (The Devil’s Blaze) was great too and am similarly hopeful the series will be revived with a third instalment at some point. Fingers-crossed!

LikeLike

I’m very grateful to you for the recommendation, given the raft of pastiches out there. I thoroughly enjoyed this, and look forward to The Devil’s Blaze most eagerly.

LikeLike