![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

An Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scotsman meet at university, where they form a club with the intention of talking about unsolved crimes. Several years later, in the manner of these undertakings in fiction, they stumble upon a fresh case and decide to take it on…only to realise that they’re mixed up in something Much Bigger Than They Imagined. Fortunately, Hugh Marsden is the ward of legendary Scotland Yard man Sir Arthur Sinclair (ret’d.) and they’re able to enlist that great personage in their predicament. Less fortunately, Sinclair has been ill for some years now, and his powers appear to be on the wane. And danger circles ever-closer…

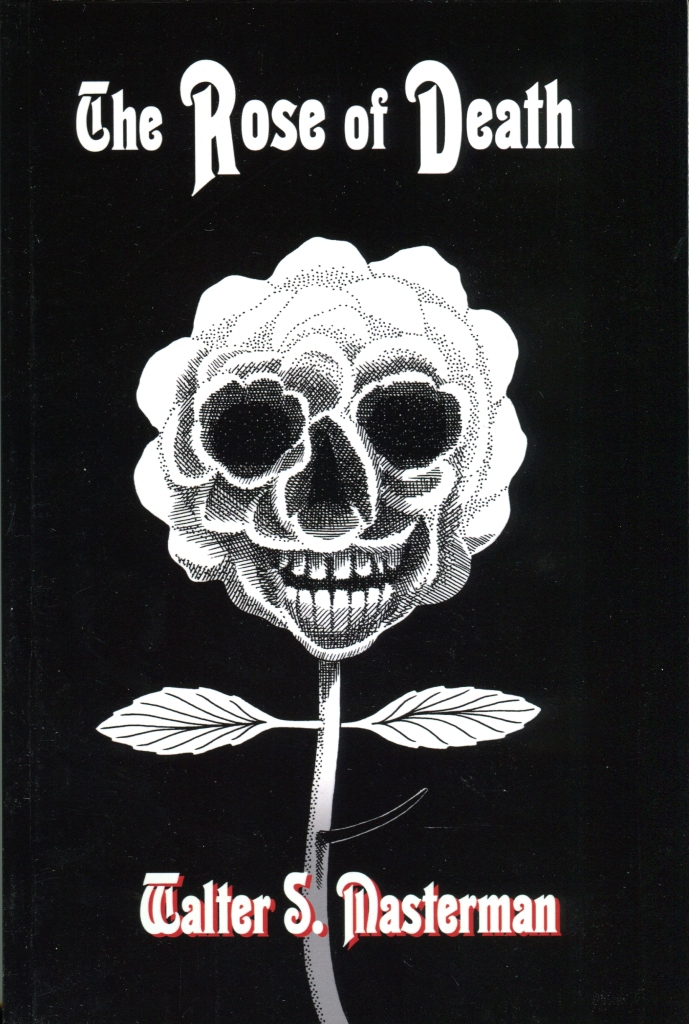

Incredible as it may seem, that paragraph above contains about 90% of the plot for The Rose of Death (1934) by Walter S. Masterman, a novel that is long on moving pieces around a board and short on any real gameplay. And it saddens me a little to call this the weakest Masterman I’ve read to date, because it has more than a few virtues — not least in that it actually feels like it comes from the year it was published, rather than 20 years earlier — but the fact remains that this nearly put me off reading any more by the man, and I’m, like, nine books deep and have another six or seven on my TBR.

The distinct lack of plot wouldn’t be guessed at from a delightfully gruesome opening sequence in which a constable on his beat is approached by a man in evening dress who has recently had one of his hands cut off. This unfortunate is treated by doctor Dick Forbes, who in turn raises the case with man about town Hugh Marsden and reporter Jack Davey, who make up the original members of the Critics’ Club. Add in wilful Betty Millard, whose induction into the club at the insistence of her straight-laced uncle is a delightful scene which really deserves to be in a better novel, and you have the four Bright Young Things whose professions, or lack thereof, give them plenty of opportunity to involve themselves in the unfolding mystery.

And then…well, then things sort of stagger to a halt, with a middle section which sees them all going their separate ways only to regather about 70 pages later and tell each other what we’ve seen them achieve to very little consequence. Then they all meet up and the villain — a man apparently above reproach in the eyes of the law, who nevertheless seems to do all his dirty work himself like some Victorian supercriminal — is caught or killed or something, I really didn’t care any more. There’s about a short story’s worth of actual plot here, but stretched over 210 pages we’re forced to endure lots of silly behaviour on the part of people who really should be more intelligent so that this technically fulfils the requirements of the novel Masterman was contractually obliged to provide by the end of the month.

It’s not without interest, not least in some wonderfully humorous turns of phrase: c.f. a club secretary “who had been divorced so many times that noone could remember her name” or a “sleepy-looking clerk who lolled over the counter waiting for the clock to strike the hour of his release”. The start of chapter XV gives an excellent capsule review of the politics of the age, too, with various newspaper headlines reported in a way that no doubt reflected the various voices in the press; and the commentary on how Hollywood movies are beginning to affect the slang used by younger generations is fascinating in its own way, not least because so little of it actually seems like slang to the modern ear.

Masterman has a good turn of phrase, too, such as describing the affair in which they are embroiled as “a black, horrible business, and the more one digs into it the more it smells of hell itself”. Equally, the perspectives taken by members of the Critics’ Club as they begin to dig into the crime is neatly shown in Betty’s reflection that “to Jack it was just a splendid game, but to her a sad tragedy”. True, it also takes some weird turns — as Masterman is apt to — like when the sinister Dr. Mortimer reveals that he’s engaged in a form of eugenics to breed the perfect servant (and that “even now, the Germans are breeding soldiers…”), and the less said about the phonetic speech of the gamekeeper Herrick the better.

All told, then, there’s little point in getting either too worked up or being too dismissive about The Rose of Death. Read in isolation you’ll not appreciate what Masterman does well compared to his other works — the characters are more neatly imbricated in each other’s lives than elsewhere, it must be said — and in context you’ll recognise it as the far weaker output that any author will produce given enough time. My advice is not to read it at all: it’s too bland to be worth the effort, and what’s done well here can generally be enjoyed in far better books from the same source. Indeed, the best idea here can be found in the far superior ‘The Adventure of the Dying Detective’ (1913) by Arthur Conan Doyle — read that, and don’t give this book another thought.

~

See also

Ben @ The Green Capsule: This is a story that features elements of suspense and mystery and that coziness of the best British Golden Age writing, but it isn’t what I suspect you and I are looking from one of these reads. Skip directly to the last twenty or so pages for the denouement and you probably experience the same amount of intrigue and satisfaction as someone who read the previous 190. … This is a comfortable ride where you’re shown the scenery as it passes before you, but it isn’t much more than that.

~

Walter S. Masterman on The Invisible Event

Featuring Chief Inspector Arthur Sinclair:

The Wrong Letter (1926)

The Curse of the Reckaviles, a.k.a. The Crime of the Reckaviles (1927)

The Mystery of Fifty-Two (1931)

The Nameless Crime (1932)

The Baddington Horror (1934)

The Rose of Death (1934)

Death Turns Traitor (1935)

The Avenger Strikes (1936)

The Secret of the Downs (1939)

Back from the Grave (1940)

Featuring Inspector Richard Selden:

The Bloodhounds Bay (1936)

The Border Line (1937)

Standalone:

The Perjured Alibi (1935)

Shame about the shapeless substance through which you had to hack, but the review was worth the effort if only for the judgement that it “… is long on moving pieces around a board and short on any real gameplay.” It’s as pithy a definition of what made the golden age shine as I can recall.

An interesting side question is which GAD novels would work best as short stories. For me, the author whose works fall into this category the most is Carr, and the author whose works do the least is Crofts.

And though Christie thought the short story was the preferred mystery form, she was, of course, equally adept at both—unlike Doyle, whose talents, as you’ve pointed out, came out much more strongly in the short form. So I’m now heading off to take you up on your final recommendation.

LikeLike

John Rhode, no doubt of it. Brilliant methods in formulaic stories.

Carr?!

LikeLike

Rhode is an ingenious pick; can you imagine the wonderful, ingenious short stories he could have left behind him?

I also generally find Edmund Crispin more successful in the shorter form. Given too much space he tends to sag.

LikeLike

Had this ben my first Masterman, I might never read him again. Thankfully, it’s like my eighth or ninth, and I’m used to his weird ways and know the joys of his unpredictable plot structures and so look forward to meeting him again for an altogether more enjoyable time.

Was Christie’s preferred form really the short story? Hers are so…average.

LikeLike

I wish I had noted the source, but somewhere she says something like that the most natural form of the mystery is the short story (which for a youthful Holmes fan like her isn’t that surprising). So she was talking in general, not about her own strengths or weaknesses. Still, I’ve always connected this with her saying that in later books she tried to delay Poirot’s appearance as long as possible. And I do rate The Thirteen Problems, The Labours of Hercules, and The Mysterious Mr. Quin very highly indeed.

LikeLike

Yes, her earlier examples are perhaps better, but I suggest she’s far, far, far less celebrated for her work in the shorter form, which is often quite forgettable.

LikeLike

That’s definitely the case. With the stories alone, she’d barely be remembered. But when she gets the balance of dense plot and minimal complication right in some of those early ones, it’s a glorious thing.

LikeLike

For me, Carr’s unmatched atmosphere and fabulous ideas tend to be let down by his detectives somehow not working that well over the long haul—though I would welcome his swapping out March for either Fell or Merrivale. My favorite Carr genre is actually his radio plays, where I think he’s the best of them all.

LikeLike

Certainly The Island of Coffins showed some wonderful ideas, superbly deployed. I understand he reused some of the principles in his later novels, and I can’t believe they’re going to work half as well there.

LikeLike

And point well taken about Rhode!

LikeLike

Nothing much to say about this one, except that even pet second-stringers eventually hack something up that’s impossible to recommend or defend. And I’m very curious to see what you make of Death on Bastille Day.

LikeLike

What’s the most objectionable perspective you can think of someone taking on Death on Bastille Day? Because no doubt I shall up end hitting that in the bullseye 🙂

And, yes, ask anyone to write enough books and they’re guaranteed to run out of ingenuity eventually. Masterman is so enjoyable elsewhere, however, that I remain optimistic about future encounters.

LikeLike

Your Masterman reviews have always made his idiosyncrasies sound enticing, and I too plan to dive in as you recommend. If you can’t be weird in GAD, where can you?

LikeLike

If you can’t be weird in GAD, where can you?

Oh, I dunno, there’s plenty of oddness out there in every genre…

LikeLike

“What’s the most objectionable perspective you can think of someone taking on Death on Bastille Day? Because no doubt I shall up end hitting that in the bullseye”

You’re not one for subverting expectations, are you? 🙂

LikeLike

Maybe that’s what I want you to think…

LikeLike

Yeah, I guess horror and sci-fi are pretty much built on that, aren’t they? Maybe it just stands out especially against the supposed base of logic or something.

LikeLike

Good point; weirdness feels weirder against a background of supposed normality. That’s how so much domestic horror became popular, I guess, but you’re right that there may be a heightened aspect of it with detective fiction.

LikeLike

Domestic horror is a really good point of reference. I think the lack of a similarly wide range of weird invention is why the fun has sermed to dim in the post GAD mystery era. Then again, Crofts showed how rich the straighter approach could be, didn’t he!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even though The Rose of Death is the only Masterman that I’ve read, I’ve still had an interest in getting back to him. It’s a strange meandering tale, with very little of what transpires actually being relevant, and the culprit is like some bizarre Victorian-era Bond villain. And yet I’m curious to read more. I’m glad to hear this is the worst of them so far.

LikeLike

Yes, do read further — I need someone to discuss these with 🙂

LikeLike

Incidentally, I’d recommend The Bloodhounds Bay as your next WSM. If you’re looking to continue him any time soon.

LikeLike

The Bloodhounds Bay is on the to buy list. I already own The Yellow Mistletoe, so it may end up being that.

LikeLike

That’s one I don’t have, so it’ll be interesting to see what you make of it.

LikeLike

Just a word of warning, The Yellow Mistletoe is not really a GAD mystery per say.

Or more specifically, it’s actually kind two books in one. It starts off as pretty much a regular mystery story, albeit flavored by Masterman’s unique style.

It very quickly changes gears though, and turns into a lost world/fantasy story more along the lines of H. Rider Haggard or Edgar Rice Burroughs.

It’s not a bad book at all, and quite interesting if you enjoy that sort of thing (though more than a bit silly in places, as a lot of the lost world books tend to be), but if you go in expecting anything even remotely like a standard Golden Age mystery story, you’ll be very much disappointed.

LikeLike

Ah, good to know — I have a feeling I might have known this, which is why I don’t own a copy (it’s an early Masterman, and when I start buying an author I like to start with their early work if I can…), but thanks for the info. I might give it a wide berth for the time being, and only buy it later if the need for completeness bites me.

Many thanks!

LikeLike