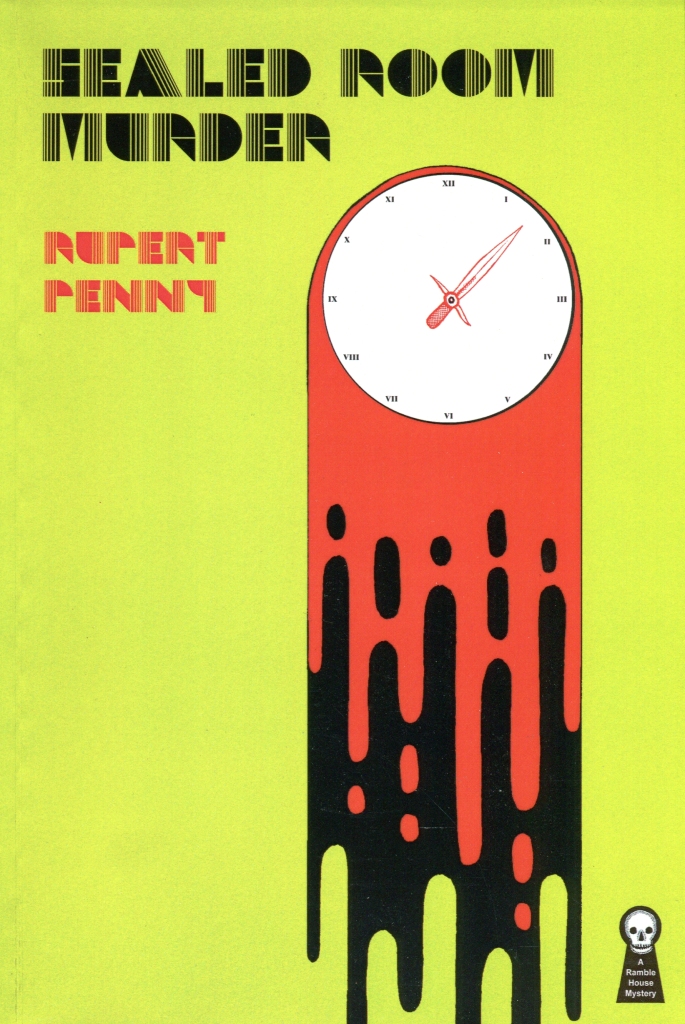

I’m pretty sure that Sealed Room Murder (1941), the eighth and final novel by Rupert Penny to feature Chief Inspector Edward Beale, was only the second-ever book I read from Ramble House, and it made me an instant fan of Penny. So now I return to it to get my thoughts on record, and see whether I’ve been remiss in singing its praises for all these years.

Told by young “enquiry agent” Douglas Merton, the murder in question is that of Mrs. Harriet Steele, widow, “who lived meanly and died hard”. When Mrs. Steele believes that someone in her husband’s family who lodge with her at The Firs is responsible for a series of domestic persecutions — mostly petty thievery, with some light sabotage thrown in for good measure — it is Douglas who is dispatched by his uncle, a one-time almost-beau of our future victim, to move into the house and investigate. There, it swiftly becomes clear that the family — consisting of Mrs. Steele’s mother-in-law, three sisters-in-law, niece, nephew, and alcoholic brother — are too much displeased by the bitter treatment they receive from the lady of the house to want to provide much aid:

The things which were being done to Mrs. Steele, whoever their author, were no more than a token of what she deserved, and I need expect no assistance in my misplaced rescue-work.

We are told from very early on that Mrs. Steele dies alone in her locked and bolted bedroom, though the murder doesn’t occur until two-thirds into the book, but how much of what goes before will contribute to the untangling of the skein? And is this book really the masterpiece I’ve been broadcasting about for all these years?

I’ll say that my initial delight at the successes of Sealed Room Murder were, no doubt, informed at least in part by my naive attitude toward small press publications. As I said above, this was only the second Ramble House book I’d ever read, and the idea that internet-only publishing houses a) existed and b) were capable of having on their roster works which were both forgotten and of good quality seemed a revelation of sorts. This second reading distinctly recalled my delight at finding that you didn’t have to be a famous name from detective fiction’s past to have put some serious thought into a perplexing puzzle, and the clarity of the problem that resulted, and the ingenuity of its resolution, no doubt seemed more startling and significant to me because I had been, unfairly, perhaps expecting a damp squib of a resolution.

Upon second read, then, I’m happy to report that the book largely stands up. The first two-thirds are maybe three chapters too long, but since some of that time is give over to a surprisingly engaging romance twixt Merton and Linda Whitehead, I can’t begrudge Penny the excess verbiage too greatly. He’s undoubtedly, I can now say — having read, to the best of my knowledge, every word the man ever published in the genre — what TomCat would call a “second stringer” in the matter of characterisation and prose, but even then he writes well and sets the gloomy and unwelcoming scene of The Firs compactly.

Dinner that night at The Firs was the worst meal I have ever experienced in my life: the poorest in quality of food and the most uncomfortable in atmospheric tension. About what we ate, or were invited to eat, it impairs my appetite even now to think for long. I still don’t know who conceived the combination of thick white soup, Irish stew, and suet pudding as fare in August: presumably either Mrs Steele herself or Olive, the housekeeper. Mrs Pippit was definitely to blame for the fact that the stew seemed composed mainly of pepper and boiled beans skins, though, and my initial dislike of her increased. As for the soup and the suet, they appeared to be the same thing in different stages of evolution, and probably were.

Or, see the slightly eldritch overtones of the following, when the sisters burn a carpet that Mrs. Steele has defaced in retaliation:

The blaze lit up the garden eerily, casting shadows which flickered and shifted and hid themselves in the encircling black. It made the women appear like creatures of another world: unreal, blotched, insubstantial things with misshapen bodies and faces the colour of flame… I wish I could pretend that anything there that night struck me as sinister, filled me with a foreboding of violence; but nothing did.

So, yes, you’re made to wait for the impossible crime of the title, but the time’s not completely wasted or filled with bland prose and token occurrences. Additionally, while I missed this time around Penny’s more usual narrator Tony Purdon, Merton isn’t quite the blank personage I’d remembered him as. Firstly, he views everyone over the age of 40 as a decrepit, decaying specimen with one foot in the grave, and secondly he exhibits a dislike towards Mrs. Steele that feels distinctly human, and avowedly aware of the horror she represents and the unfairness of the discomfort she is deliberately visiting upon those who surround her: “I should have enjoyed beating hell out of her,” he tells us at one point, which is hardly the most chivalrous position adopted by a Golden Age narrator.

When Chief Inspector Edward Beale is ushered into events, the novel kicks into a fairly high gear, with investigation high on the agenda and some unusual clues ready and waiting to be declared. I’m not completely sure how Beale reaches the answer he does from the clues provided — Penny himself calls a detailed answer “too much to ask for or expect” in the Challenge to the Reader — and had completely forgotten that Penny gets around Beale’s lack of explicitly explaining the clues by having the workings of the crime detailed in an impersonal manner through italicised font as if explaining something of a technical, rather than narrative, nature. And impressively technical it is, too, relying on five diagrams to piece it all together, and displaying a level of cleverness rarely seen outside of this Grandest Game in the World.

I appreciate now that Penny had developed a staggering propensity for complex plotting — try explaining She Had to Have Gas (1939) or Sweet Poison (1940) in under a paragraph — and the relatively straight ahead nature of this is pleasing given just how damn complex some of his later schemes became. And it ends on a delightfully human note, too, not unlike He Who Whispers (1946) by John Dickson Carr (though without the moral greyness that makes that final line so compelling), bringing the human element of that conclusion back to the centre of proceedings where elsewhere he had a tendency to tie up the technical ends and then dust his hands of all concerns.

So, well, I thoroughly enjoyed this second visit to The Firs, and while I might not consider this the nailed-on masterpiece that I’ve been calling it for the last eight or nine years, I still say Penny has more to offer the student of the classic novel of detection that practically anyone else who wrote in the second strata of the genre during its richest period. I’ll remain forever regretful that he left only nine novels and no short stories for us to remember him by, but at his best he was a superbly enjoyable, creative, and downright baffling proponent of classic detection, and deserves remembering for the excellent work he did time after time. I recommend giving him the time of day if complex plotting and innovative schemes are your jam, and have already put together this guide for the curious…so no excuses!

~

See also

Noah @ Noah’s Archives: If you’re a fan of the Golden Age mystery in general, you may enjoy this; you won’t be ecstatic, but you will be amused…the focus is on the personalities of a group of unpleasant people trapped in a restricted setting, strung together with a mawkish and not especially believable love story…It also reminded me of [Ngaio] Marsh because there is a big sag in the novel as the author introduces the characters and their individual personalities and backgrounds, and the action more or less slows down to a crawl while the stage is set. Marsh is well-known, at least to me, for that problem of construction. However, unlike Marsh, the sag in Sealed Room Murder happens before the commission of the murder; in the traditional Act One/Two/Three structure of this novel, Act One is far too long, Act Two is uncharacteristically abbreviated, and Act Three is a mere 20 pages in which Inspector Beale Explains It All… So the construction is not especially good, but at least it’s different than the usual run of such mysteries.

~

The novels of Rupert Penny, published by Ramble House

Featuring Chief Inspector Edward Beale:

The Talkative Policeman (1936)

Policeman’s Holiday (1937)

Policeman in Armour (1937)

The Lucky Policeman (1938)

Policeman’s Evidence (1938)

She Had To Have Gas (1939)

Sweet Poison (1940)

Sealed Room Murder (1941)

Standalone:

Cut and Run [writing as Martin Tanner] (1941)

I was wondering what you had prepared for us today to disagree on. Sure enough, Penny’s Sealed Room Murder will do the trick, but you already know why it didn’t work for me. I agree there’s an attractive level of cleverness to the solution, which regrettably falls flat coming after an overlong, tedious preamble of domestic bickering and vandalism. Sealed Room Murder should have been cut down to a shorter length or presented as a semi-inverted mystery, which tells the reader who’s plotting a murder, but not showing how the murder is carried out. Now that would have been a classic impossible crime novel!

“…and while I might not consider this the nailed-on masterpiece that I’ve been calling it for the last eight or nine years…”

Wait… so we agree on Sealed Room Murder after all? We’re truly living in strange times.

LikeLike

It’s an even more interesting book to reread in light of Penny’s career before this, which really played around with structure for a couple of books. And it’s about a third as complex as the couple of books which preceded it, too — seriously, She Had to Have Gas, as well as being an unintentionally hilarious title, is surely one of the most densely plotted books the genre ever produced.

But, well, on its own merits, yeah, it’s flawed, but I still love it.

LikeLike

I have this one on the big pile so still need to read it. This does seem to be a Marmite-type of book (i.e., a reader finds it appealing or strongly dislikes it).

Interestingly, Michael Crombie (pseudonym of James Ronald) has a similarly titled book, “The Sealed Room Murder”, which I am keen to read if / when it becomes available at a reasonable price. I have only seen it for sale online 2-3 times but always priced exorbitantly given its obscurity.

LikeLike

Like you, I’ve seen the Michael Crombie book for sale a couple of times and have failed to afford it. Maybe — given that we’re getting at least one volume of Ronald’s crime writing — we won’t have to wait too long for that to become affordable…

LikeLike

There are two more volumes planned: Stories of Crime & Detection, vol. II: Murder in the Family (also includes “The Monocled Man” and “The Second Bottle”) and Stories of Crime & Detection, vol. III: This Way Out (also includes Diamonds of Death and Ruined by Water).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hot damn! So there are!

LikeLike