Like a lot of people, I’m sure, I got on a classic movie kick in my teenage years and watched many of the greats, including much of Alfred Hitchcock’s work. It is only recently reading The Wheel Spins (1936) by Ethel Lina White, however, that brings me back to Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938) for the first time in over two decades.

And, god, it takes an age to get going, doesn’t it? The first third is given over to the denizens of a crowded hotel in some unspecified corner of Europe as people wait for an avalanche to be cleared from around their train. There’s some good light physical comedy involving the hitting of heads on exposed beams, a pleasingly stuffy pair of Englishmen (“You can’t be in England and not know the Test score…!”), and the first interactions of our main characters, but, whew, it’s far from necessary. It rings the changes of White’s novel with Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood) heading back to Blighty to marry some titled man she probably doesn’t love (rather than travelling alone because she’s sick of the crowd she’s been rolling with), and receiving a blow to the head on the station platform when returning the glasses Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty) drops (rather than collapsing from sunstroke…though, now I think about it, the sunstroke is described in the novel like a blow to the head) — a blow which we know seemingly aimed at Miss Froy — but, yeesh, you can skip the first 20-odd minutes, their sole interest being the strangulation of a guitarist who might be killed just to shut him up.

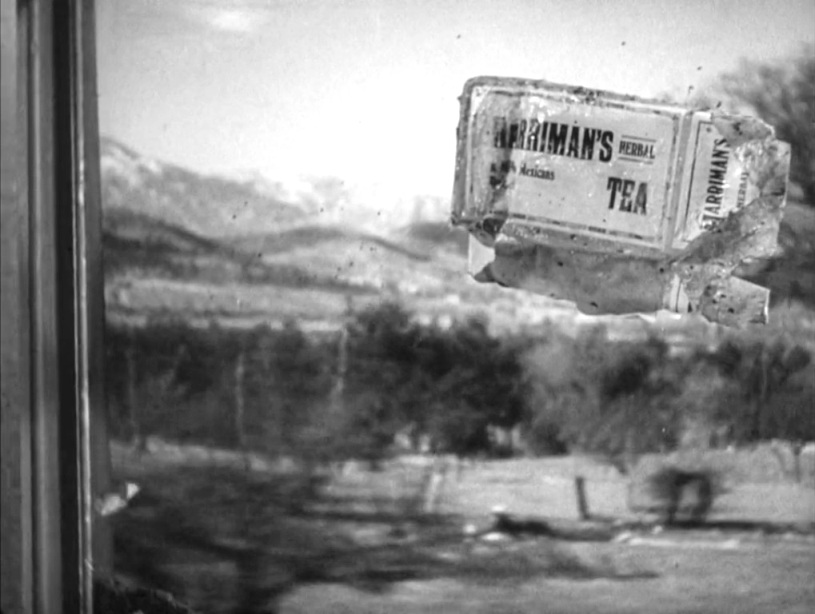

Some subtle changes shift events from the central section of the novel, with it being clear once we’re on the train that honeymooning couple the Todhunters (Cecil Parker and Linden Travers) are anything but — slightly spoiled by their listing in the opening credits — and the conceit of Miss Froy writing her name on the window ingeniously moved to allow for a great moment of suspense later on. From here, things largely play out as in the book: Iris awakening from a sleep to find Miss Froy vanished and the other passengers in their compartment insisting there never was such a person. Cue Mr. Todhunter also denying it, and brain specialist Dr. Hartz (Paul Lukas) taking an increasing interest in Iris’ insistence. In a wrinkle introduced by the film, those stuffy Englishmen (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne) also get in on the denial due to their eagerness to get a connecting train so that they might make it to the cricket — and the fact that we know people are lying from the off is a good decision, and one that supports the oddness of the setup.

It’s another good decision that Gilbert Redman (Michael Redgrave), renamed from Max Hare in the novel, maintains his presence of neutrality throughout much of his initial involvement — Redgrave is undoubtedly a friendly presence, and a stronger personality than his book counterpart, evinced through superbly-delivered lines (“My father always taught me, never desert a lady in trouble. He even carried that as far as marrying Mother.”) — before becoming a believer in Iris’ story just past the halfway point. The film needs a central relationship to hang its final third on, and the two of them in consort have more chemistry to allow later events than Iris alone. It also gets us through the part of the book where White was filling us in on the reasons many of the witnesses had for wishing to avoid involvement — which, as noted, we already know — and so makes this a more intriguing, more filmic experience.

Given that Hitchcock never leaves the train once it’s in motion, more is needed to fill out this final section, and the investigations undertaken by our central pair pieces things together in a more pleasing way than the book managed. At least one of the passengers is given more life, there’s a fist fight, a brief piece of no doubt hugely-influential action, and the workings of events are revealed in a brilliant moment of immediate reversal that sort of takes your breath away. There’s also a more deliberate shape to the actions which bring about the justification of Iris’ concerns, rather than the almost accidental means adopted in the book, and all this gives the last 20 minutes much more life than the final pages of the novel would have achieved if put on the screen exactly as on the page. It also, delightfully, enables perhaps the most English reaction to being shot ever recorded on film.

As a piece of adaptation, The Lady Vanishes shows the benefit of respecting the essence of source material without slavishly sticking to that which doesn’t translate well. The MacGuffin is pure, delightful nonsense, but that doesn’t make any of what it allows any less enjoyable, and goes to show how a clever idea, well-deployed, can support a great deal without having to get over-complicated — a lesson it feels screenwriters today could do with learning. As a piece of old-school film-making, with model work and back projection well-used to provide atmosphere, it’s a charming and intelligent piece of work, even if it doesn’t represent the heights Hitch would reach when he crossed the pond a few years later. I just wish those opening 25 minutes weren’t so dull…

This is one of the weaker Hitchcock efforts from his string of 30s hit thrillers. I think its reputation is mostly based on the hook — this one is easier to remember than the others. Sabotage (36), The 39 Steps (35), The Man Who Knew too Much (34), and Young and Innocent (37) are all better films.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s fair to say that all those films are better examples of Hitch’s work from this era.

LikeLike

You have the advantage on me as I have not read the book, but in my experience, Hitchcock never met a written work he didn’t improve upon adapting – with the exception of Iles’ Before the Fact, where the censors wouldn’t let the director end Suspicion the way he wanted to. TLV is a charming film that I rarely return to, for all the reasons you say. That fey British humor takes up too much time, and given how world-shattering the work of Miss Froy is, all those excuses people have for lying about her presence tend to cumulatively annoy me rather than fill me with suspense. But the central trio are charming, the villain even more so (as often happens in Hitchcock) and that bit with the train window is a classic AH moment worthy of rewatching!

LikeLike

In fairness, if those cricket chaps knew that she was working to preserve the integrity of dear old Blighty I’m sure they’d be at the front of the queue of people insisting something should be done.

Read the book, though, especially now it’s easily available. The two make a very interesting comparison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the opening is utterly charming, I’ve never found it slow. TLV is certainly lighter than the other political thrillers Hitchcock directed in the 1930s, probably as Launder and Gilliatt originally wrote it with Roy Willian Neil assigned to direct before he bowed out.

LikeLike