![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Young Iris Carr is travelling back to England alone when she is befriended by governess Winifred Froy; taking tea in the dining car of their train, they return to their carriage, where Iris falls asleep. Upon awakening, she finds Miss Froy has disappeared and, more confusingly, that all the forriners sharing the compartment insist there never was such a lady to begin with. Might the attack of sunstroke Iris suffered on the platform before boarding be to blame, or might there be a more sinister explanation? Thus The Wheel Spins (1936) walks in the same furrow as a good many suspense stories, not least Phantom Lady (1942) by Cornell Woolrich and the Jodie Foster-starring Flightplan (2005).

The key to such a setup is, of course, the isolation of your protagonist, and Ethel Lina White does a great job of cutting Iris off from those around her from the very first page. Tiring of the smart set in whose acquaintance she has passed her entire adult life, Iris has stayed on an extra day at their mountain-shrouded hotel where she is the only one without a travelling companion, and her general attitude to life and those who surround here is one of tolerant condescension: “She had been spoiled since her birth, so it was natural for her to be selfish”. Thus throwing herself on the sympathy of strangers doesn’t come easily, and represents almost as much of a horror as the inexplicable vanishing of a woman she barely knew and certainly paid very little attention to.

This makes Iris sound like a difficult protagonist to root for, but one of White’s triumphs is the way she explores the faults and foibles of the people involved, often against their will, in Miss Froy’s vanishing. Iris’ borderline obsession with finding English witnesses, whose veracity she feels can be trusted purely on account of their passport, reads like a commentary on the naivety and obstinacy of youth, and is delightfully unpicked in a central section which tours the various people whose help has been sought and explores their reasons for either deliberately avoiding involvement or behaving as if such a happenstance is rather infra dig. Equally, when Iris finds such preconceptions turned against her, she is of course horrified, and must find a way to both convince herself of her rightness and fight through the stonewalling which faces her at every turn.

The shades of gaslighting and denial which pervade this — even to the point that Iris herself starts to give her convictions up as delusions — make it seem like a very modern book, though White thankfully has a light touch with this thread, and as such builds the horror in the situation well. It’s a shame that she makes the choice to fill her story out with a patchwork of wider considerations which take attention away from Iris, since that dilutes the suspense, but at the same time it can be easily understood that the core conceit isn’t really enough to support a whole novel on its own. A secondary plot thread might have enabled this to sustain focus, but that’s very much not White’s intent and you have to admire how she keeps the core problem so front and centre at all times.

She also writes excellently…

She believed that she had emerged into the daylight and her heart was still singing for the joy of deliverance. But she had been deceived by a ray of sunshine striking through a shaft in the roof.

…and, in providing an explanation for events, does some marvellously subtle work in interpreting little actions which this reader had taken for granted. The temptation must have been strong, too, to find support for Iris Carr, since facing so stark a conundrum alone is a hard task, but White manages to keep her isolated, and so doubtful, for an incredibly long time, finding sympathy if not exactly acceptance or belief among her fellow passengers: Max Hare is thankfully not set up as some romantic saviour, and it’s completely believable that he and others would act as they do while seeking to remain distant from events. The people in this really are superbly realised, but that’s something which has come though in all of the little work by White I’ve read to date.

Robert Adey lists this as an impossible crime, and I suppose the crowded nature of the train renders the killing and/or disposal of Miss Froy very, very difficult, but I remain a little sceptical of its impossible credentials if only because Hare’s own “admittedly feeble” suggestion of events shows how very possible such an effect might be easily achieved. It’s not the book’s fault, but as a student of the impossible crime I feel I should raise the objection. As to the faults within the narrative, it’s a shame that the explanation of events is achieved not by some clever oversight or subtle clue placement but instead by…well, the almost accidental means employed, undercutting the ingeniously inverted tension of that final section. Something cleverer would earn this an extra star, because it really is a delight for most of the journey, and just a shame that what we’re building towards isn’t more rigorous.

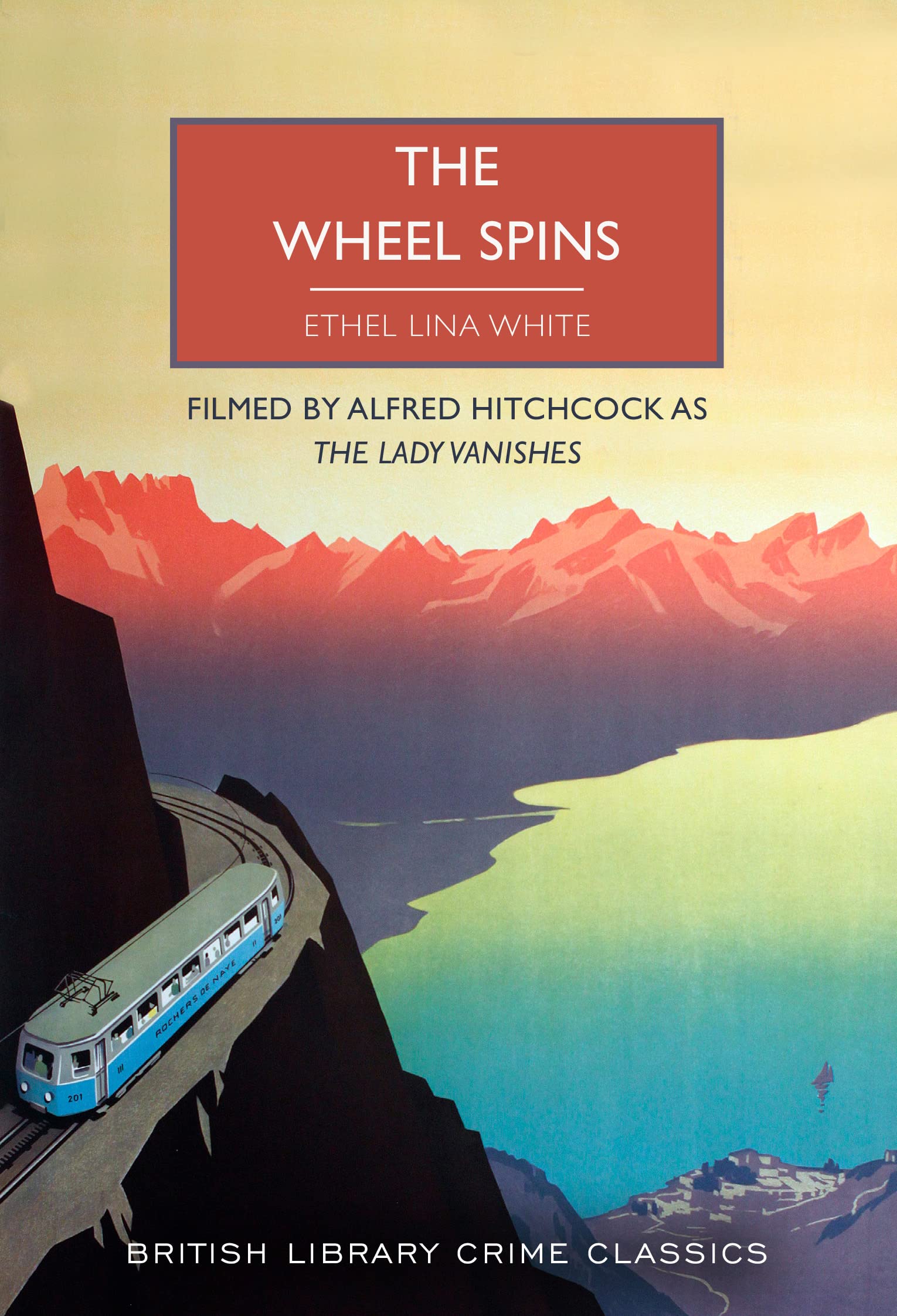

On this evidence, though, it would be lovely to see more of White’s work included in the British Library Crime Classics range; one can understand it being picked on the back of the popularity of the Alfred Hitchcock film spun from these pages — I rewatched it after reading this, thoughts coming on Saturday — but White is clearly strong enough to stand on her own merit. My thanks to the BL for the review copy, and here’s hoping it’s not the last of her we see in this excellent series.

Saw the film recently. Now looking forward to reading the book. Thanks for an excellent review as always, Jim!

LikeLike

The film is an interesting watch in light of the novel — you see the benefit of moving around certain pieces, yet al while staying true to the source manuscript. Thoughts on this on Saturday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed the film, the original Hitchcock one, not the later version. The book was very different but was equally enjoyable.

LikeLike

Yes, I didn’t realise it had been filmed three times — and that’s just in English. The original film definitely has some flaws which you can see latet filmmakers looking tonimprove upon…but more about that on Saturday.

LikeLike

I am surprised you enjoyed this one as much as you did, as I know you have not enjoyed some of her other work. I am in the minority I think in saying I didn’t really enjoy the Hitchcock adaptation, finding the plot too silly. I much prefer the 2013 BBC adaptation which improves upon the ending of the book (which I feel falls a little flat).

LikeLike

Fear Stalks the Village is the only other novel of hers I’ve read and, yes, that one didn’t work for me. But the short story in Crimes of Cymru is excellent, and her works in the Bodies from the Library collections has shown real promise, so I’d love to read further,

Interesting, too, to think of a more modern adaptation being more successful. You almost make me want to track it down…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sometimes comes up on BBC iPlayer but it doesn’t seem to be there at the moment.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree: ‘White is clearly strong enough to stand on her own merit.’ For my own idiosyncratic take on the novel in relation to the film, see: http://harryheuser.com/2023/09/29/gaslight-express-ethel-lina-whites-the-wheel-spins-the-vanishing-spinster-and-the-freewheeling-single-englishwoman/

LikeLike