It feels fair to say that the work done thus far by Dennis Lynds in the Three Investigators series, under the nom de plume William Arden, represents the solid and unspectacular middle ground while those around him — Nick West, M.V. Carey — plumb both the highs and the lows.

Lynds’ first three books — The Mystery of the Moaning Cave (1968), The Mystery of the Laughing Shadow (1969), The Secret of the Crooked Cat (1970) — are pretty forgettable fare, playing reasonably safe and finding little new to do with juvenile sleuths Jupiter Jones, Pete Crenshaw, and Bob Andrews. Leave it to West to write perhaps the nadir of the series so far with The Mystery of the Coughing Dragon (1970) — and then redeem himself with the excellent The Mystery of the Nervous Lion (1971) — and then have Carey write the post-Robert Arthur high of The Mystery of the Singing Serpent (1972)…but Arden’s contributions are something I’d fail to be drawn on at this stage.

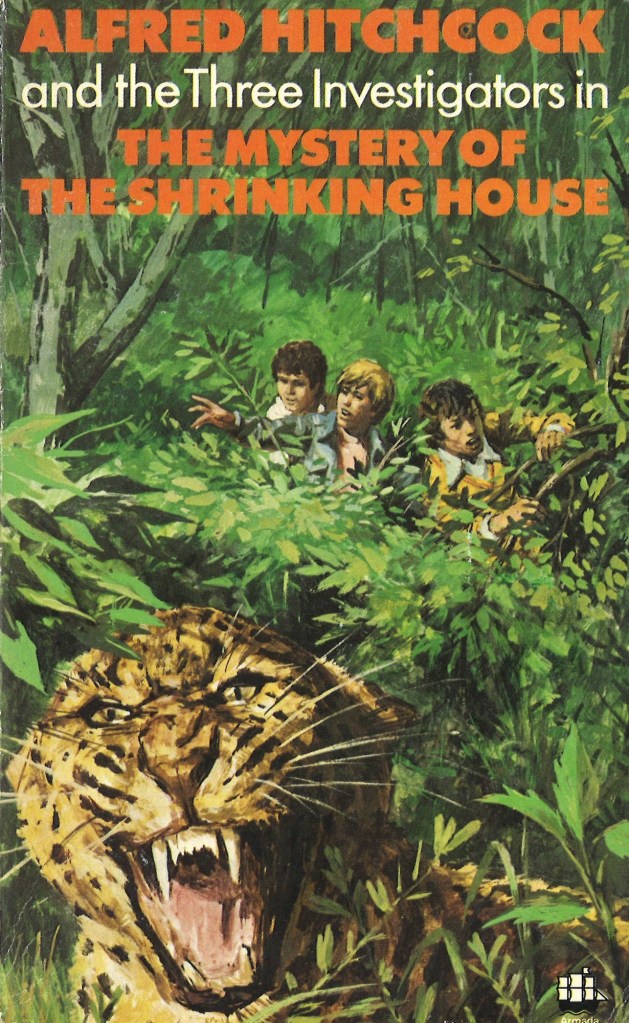

Which makes the complexity and competence of eighteenth title The Mystery of the Shrinking House (1972), Arden’s fourth of an eventual thirteen titles in the series, all the more surprising and delightful. Maybe taking a couple of years off gave him the opportunity to adjust his thinking, or maybe it’s a complete fluke and everything else he wrote from this point on is as bland and forgettable as the work put in prior to this book, but at present I’m willing to believe that William Arden turned a corner here, and that the boys were well-treated in the next fourteen years spent in his company.

Vaguely aware that this title included some sort of impossible crime, I went in assuming the eponymous house and its changing size was going to be the miracle problem that needed explaining, but Arden’s title is instead a reference to the diminishing size of the dwelling painted some twenty times by impoverished artist Joshua Cameron. It is following Cameron’s death that Professor Carswell, Cameron’s one-time landlord, contacts the Jones Salvage Yard to sell on the artist’s belongings in the hope of recouping rent owed, and Titus Jones and the boys take these twenty paintings along with the other knick-knacks which might be of some value to someone else.

Little do they appreciate the stir this will cause: a week later, a lady claiming to be both European nobility and Cameron’s sister calls looking for the paintings, and she is succeeded by sinister art collector Mr De Groot, whose vaguely threatening ways put the boys on guard. And then — cue a roll of the eyes from me, having never really been a fan of the character — E. Skinner “Skinny” Norris is mixed into events, too, and before long our central trio are trying to help the Countess while keeping out of De Groot’s clutches, giving events a pleasingly complex structure from a fairly early stage.

Now, in fairness to Arden, the utilisation of Skinny Norris is done well, with the character’s antipathy towards the Three investigators driving the second half of the plot, and allowing one decent suspense sequence which shows Bob Andrews as an intelligent and brave member of the trio (he’s normally there to quip and raise objections). Indeed, one of the subtle successes of this book is how Arden continually manages to divide the central three boys up, so that there’s usually one missing in every situation who is in turn able to push events on. The tendency to group all tree of them together must be strong, and in my memory it’s happened a lot in the preceding books, so Arden’s done well to recognise that element of this series and pry it open a little.

This leads us to artist Maxwell James, and the impossible situation found herein: namely that several paintings stored in his studio seem to be moving around in the night:

It was a large studio, equipped with racks for everything. Light poured in through two casement windows and a big skylight. The windows, which opened inward, were solidly barred on the outside. The skylight did not open at all. There was no fireplace or stove. A small exhaust fan was built high into the rear wall; an electric cord dangled from it down to a socket near the floor. The floor itself was solid stone, with no basement underneath. There were no hollow places in the floor or in any of the walls. A simple, solid, fortress-like room, with no way in or out except through the single door.

The door is locked every evening by James himself, and yet in the morning the paintings have definitely moved. A half-decent false solution is suggested in a single line of dialogue, but to solve this problem once and for all it’s decided that one of them will hide in the cupboard and observe and…well, the solution is a little underwhelming, but the explication of it is at least livened up by Pete having to hide in a cupboard filled with paint thinner, so that he begins to hallucinate semi-nightmarish visions once the origin of the movement is ascertained.

So the impossible element of this disappoints — hardly surprising, it’s not going to set new records for ingenuity — but what is pleasing is the complexity of the reasoning employed in the closing scenes when various connections are made and the culprit eventually caught. It’s a trope of this series that the final scene of each title has the boys explaining things to Alfred Hitchcock while glossing over some key details, but Arden’s summary is intelligently-argued and surprisingly rigorous given what has been allowed to stand in previous books. And the logical connection which Hitch overlooks is a nice touch, too, showing that more thought has gone into this plot than certain others. If Arden keeps up this level of construction, he may yet turn out to be my favourite writer in this series.

I mean, sure, you have to allow for the Chief of Police sending three teenagers and an old man in pursuit of an armed suspect, but, well, the 70s were a different time, weren’t they?

It’s too early to tell, of course, but the last two titles in the series really do feel as if the editors behind it are getting a good grip on what they want these books to be: well-reasoned, entertaining mysteries that don’t short change the readers in complexity and creativity while remaining firmly focussed on the capabilities — and occasional fallibility — of the central trio. It’s entirely understandable that in the wake of Robert Arthur’s death it might have proven difficult to steer a consistent road with his creations, but Carey and Arden seem to have righted things now, and it’s to be hoped that this recent standard is maintained going forward. I will have to start tracking down titles thirty to forty-three tout de suite!

~

See also

TomCat @ Beneath the Stains of Time: The Mystery of the Shrinking House provides a surprisingly rich and intricate tapestry of plot-threads, which range from the (hidden) secret of the dead painter and his cryptic last words to the driving motive of all the characters and a small locked room problem as the cherry on top – which results in a really involved and complicated plot. Once again, I was pleasantly surprise to find such a plot in a series of detective stories targeting younger readers. One of the three best I have read from this series thus far.

~

The hub for Three Investigators reviews can be found here.

This is still one of my favorites and I think you’ll enjoy Arden’s The Mystery of the Headless Horse. If only for the conclusion to the Skinny Norris arc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s certainly a good one, easily one of the post-Arthur highlights along with Nervous Lion and Singing Serpent.

The next title in the series — Phantom Lake — is another one by Arden, so I’ll be interested to see how that turns out. It really does feel as if the people in charge have a good sense of where they’re going now, and it would be wonderful if we could have a run of strong books for the next little while…

LikeLike