![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

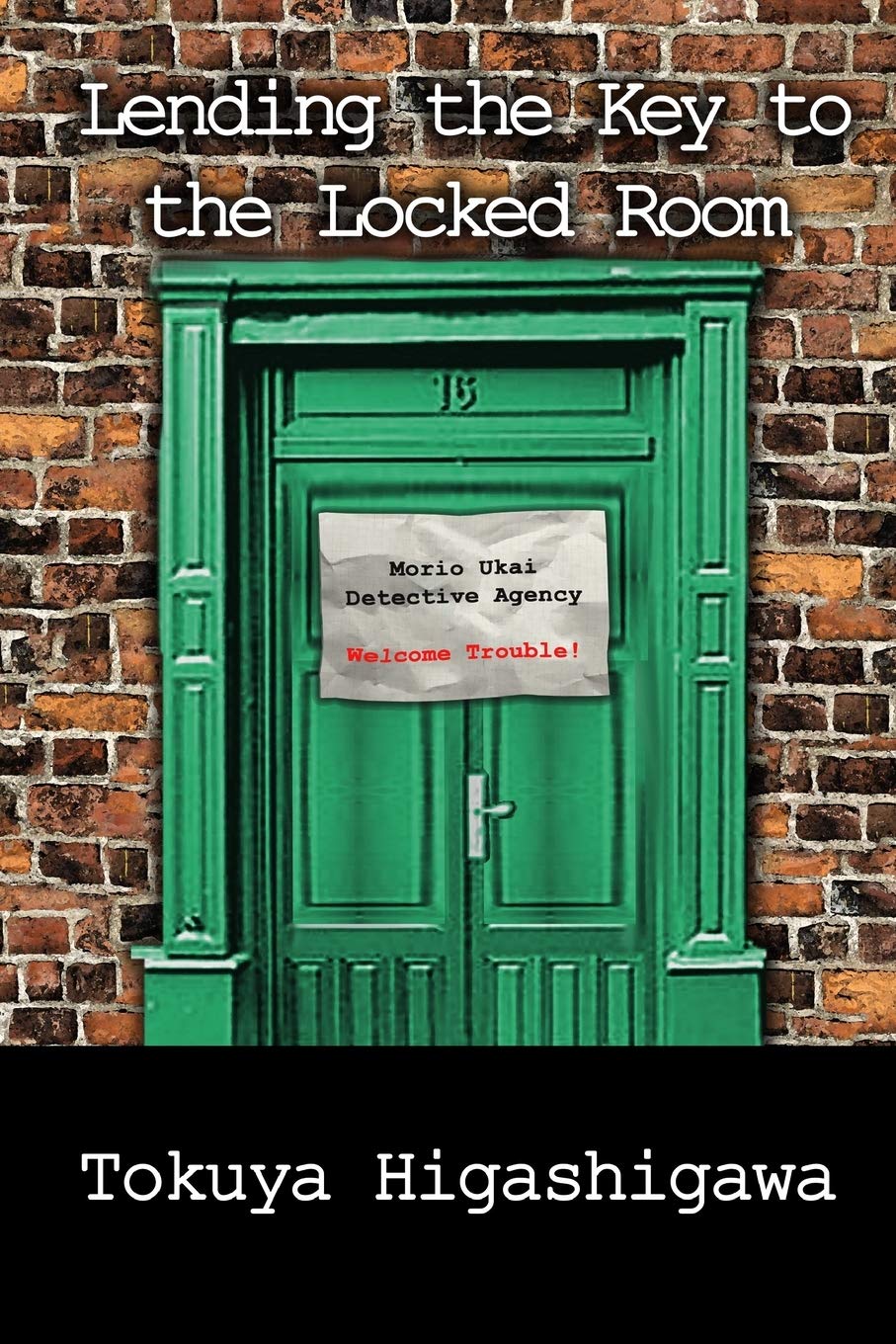

The sixth translation of (shin) honkaku by Ho-Ling Wong under the auspices of Locked Room International, Lending the Key to the Locked Room (2002) is a paean to the glory days of the complex puzzle plots of the 1930s while oddly frugal in its own plotting and characterisation. Delightfully self-aware at times in a manner that (to my taste) never succumbs to the danger of outstaying its welcome, the savvy elements of this debut are undercut by issues elsewhere: a reliance on concidence, a tiny cast with very little to misdirect into, and the sheer amount of irrelevant information that carries you through.

After a fair amount of time spent introducing us, very drily, to Ikagawa City — “a bedroom town for white collar workers who spend their day in the metropolis” — we meet the two people we’ll be mostly concerned with: film student Ryūhei Tomura and his filmmaker friend Kōsaku Moro. On one of their usual film-watching evenings in Moro’s specially-designed screening room (complete with video player — remember VCRs?!), Ryūhei finds himself confronting Moro’s dead body and the fact that he, Ryūhei, is the only other person in a flat locked from the inside.

So, should he then just unlock the door chain and flee the scene?

The locked room would cease to be locked from that point on and, as a result, the police would not be able to automatically build a case to finger Ryūhei as the murderer. Ryūhei didn’t have a motive to kill Moro in the first place, so the police might not even view him as a suspect in the case.

Of course, he flees, but has the good fortune to have a private investigator as an ex-brother-in-law, and so is able to find an ally in his search for exoneration. Can Ryūhei and Morio Ukai find the truth before Chief Inspector Sunagawa — “Not married, no children. No debts. No criminal record. (What a guy!)” — and his subordinate Detective Shiki end up joining the various dots to form an arrow pointing in their direction?

About 100 pages remain once this situation has ben established, and not all of what has come before is necessarily done well. When Ryūhei first meets Ukai, for example, he relates the details of the previous evening (in indirect speech, since the reader has already seen this) and then Ukai repeats it back, in direct speech, for us to listen to again. Equally, Higashigawa takes time out early on to inform the reader that more than one perspective will be observed in the narrative…something which has been done in practically every other translation I’ve read without the need for explanation. Maybe he’s trying to up the artificiality to distract away from what is, after all, only a very simple puzzle, but it’s an odd way to go about it if so.

I enjoyed the interventions Higashigawa undertakes to reassure us, say, that the geographical arrangements he’s just furnished us with aren’t particulary helpful or useful, or his frustration that he has to describe the appearance of the characters (“If only I could just show you a photograph of him.”), and the humour focussed mostly on the policemen also hits some knowing notes. Not unexpectedly, there’s also a slight commentary on the preponderance of murder puzzles: in the form of the movies that represented something of a Golden Age in Japan for the genre (which I mistook as a Star Wars (1977) reference…) as well as those of the printed variety:

“The numerous mystery novels I’ve read, and the countless locked room murders that occurred in those stories, have all become part of me. They whisper to me in my mind. They tell me that your locked room murder is simple. There’s no need to make something difficult out of it. It’s a simple trick that anyone with a love for mystery novels will see through. That’s why I said I had an idea how to solve your locked room murder.”

The explanation when it comes has some good clues behind it — one in particular is especially gorgeous — but plucks a motive from the clean air that consequently feels rather foisted upon us and fails to ring true. The puzzle itself is classical and fairly easy to anticipate — though I’m more than happy to admit that I was looking in completely the wrong direction with one key part — but watching the patterns and possible explanations eventually make their way to the surface is always fun, even if it does feel rather drawn out at times. It left me thinking of ‘The Five Clocks’ (1957) from The Red Locked Room (2020) in that the solution is very interesting, but seeing how our investigators came to realise it would be even more so.

All told, Lending the Key to the Locked Room isn’t going to knock The Moai Island Puzzle (1989, tr. 2016) from its perch as my favourite of the honkaku LRI has brought us, but if you’re looking for a playful, functional puzzle that never tries to do more than enjoy itself you could do much worse. Full respect to Ho-Long for another clean, uncluttered translation, and here’s hoping more are due in the near future.

~

See also:

TomCat @ Beneath the Stains of Time: [E]verything about the plot, despite some modern touches, reminded me of early period Christopher Bush with a plot revolving around two murders committed within “a very short time-frame” and the two detective each finding a part of the overall solution – not to mention the presence of a brilliant alibi-trick with the locked room angle being a bonus. Nearly everything fits together perfectly, clues, red herrings and the general cussedness of things, but there are a few smudges and imperfections.

Brad @ AhSweetMysteryBlog: I figured out three-quarters of [the] solution because it was the only solution available (and therefore it was especially galling that not one of four sleuths ever gave it a mention until the end!); the rest of the answer was impossible to determine, for reasons outlined above. There is one Christie-like clue towards the end that works, but it’s tied to such a wild coincidence that it was a bit spoiled for me. The motive for one of the murders was actually quite clever, but I think that, in the hands of a Christie or a Queen, perhaps, it could have been set-up so much better.

Aidan @ Mysterues Ahoy!: Though I am a little reluctant to label this as a comic detective story, in part because the humor is not frequent enough to feel like the purpose or focus of the story, Higashigawa does approach telling his story in a rather light-hearted fashion. His narration is peppered with little comments that acknowledge that we are reading a detective story, reflecting on the expected structures and plot developments of such works. They prompted more smiles than laughter for me but I still appreciated their inclusion and felt it fit well with the general craziness of the story’s premise.

A paltry three stars? You’re right about the motive and it’s a smudge on its otherwise first-class plot, but all else makes it a perfect representative of everything I’ve come to appreciate and love about the Japanese detective story. I suppose having had more exposure to it through Case Closed, Q.E.D. and the Kindaichi franchise also helped appreciating what Tokuya Higashigawa tried to do here, which made for an impressive debut in spite of some minor smudges.

So glad you liked it for the most part, but I think its deserving of four stars.

LikeLike

Hey, you’ve got a copy of the contract, just as I have, and you know full well about clause 7B/iv — about the need to make a sacrifice to Baphomet if we agree more than four times per “orbit of the Sunne”. Let’s…not use them all up in the first half of the year, eh?

LikeLike

Four stars? Five at least! j/k

Thanks for the review! As for new shin honkaku coming… Who know, perhaps there’s something coming! (he said knowingly)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whtever it is — always assuming something is on the way — I’m excited to read it. You’ve done such a great job with these, and those of us too damn stupid to learn other languages are gigantically appreciative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I apparently enjoyed this a whole lot more than you. An easy four and a half stars. Dry prologue notwithstanding, the story just hurtles forward at a pace even greater than your average, already brisk shin honkaku thanks to the rather Hitchcockian narrative, told from the point of view of the fugitive who finds himself in a jam and seeks to clear his name while evading the authorities. And the ratiocination that begins with a pistachio shell is brilliant and better handled than a similar yet far more longwinded and somewhat wearisome scene centering on bicycles at the end of Moai Island Puzzle. For my money anyway. Can but hope the wait for the next honkaku release from LRI is a short one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I sort of expect the general impression of this to be more positive than mine — I love an ingenious piece of reasoning (as with the shell, ike you say) but also want to know how the investigators reached their solution. This, I think, is part of what makes Crofts so fascinating to me — though, in fact, I think it may have been Crofts’ rigour that made me come to really appreciate the process when I see it on the page (you may order that cart and horse as you like).

The next LRI honkaku has just been announced as Death Among the Undead by Masahiro Imamura — impossible crime + actual zombies! Frankly, I cannot wait…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read a single Crofts, the Sea Mystery and supposedly one of his better ones, which had an outstanding chain of logical deduction early on, perhaps too soon, because the promise of more of the same later on never really came to fruition. Still, he’s someone I plan to return to in due course.

Appreciate the news regarding the next honkaku. Sounds a little offbeat I must say, but the sub-genre has been such a reliable wellspring of intellectual stimulation and delight for me, specifically those released by LRI, that I fancy it’ll turn out to be another winner.

LikeLiked by 1 person