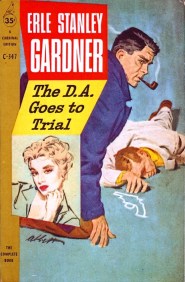

I maintain that the Doug Selby novels of Erle Stanley Gardner stand as probably his best work, and only the genius of Raymond Burr, that awesome theme music, and the fact that the Perry Mason novels outnumber the Selby ones by a mind-blowing 9:1 ratio have led to the relative obscurity of this better series. “What about the Cool and Lam books?” you want to know? Well, as soon as I’m done with Selby I’m going to go and read all 30 of those in order, too, because probably two-thirds of them eluded me back when I started reading Gardner and so there are plenty of gaps to fill. So officially the jury is still out, but the Selby books remain fabulous nonetheless.

This is the point where the series begins to resemble a long-running soap opera, with strands all now in place to play out in good time. Alphonse Baker Carr was introduced in the previous book, The D.A. Draws a Circle (1939), and has no part in this one, but we do get the return of Inez Stapleton following her fleeing the scene a couple of books back. And apart from the fact that there’s waaaaay too much comparing the practicing of law to the playing of tennis she’s the focus of some of the most interesting themes in the books ahead. The promised eponymous trial that should pit her and Selby mano a mano here doesn’t pay off in the way you’d hope, but there’s plenty of other stuff to keep you entertained in the meantime.

Now, pay attention: this gets a little complicated. Essentially there are two threads — the first concerning a hobo who has been hit by a train and must be identified, and the second a request from the neglected neighbouring city of Las Alidas to look into a man who has apparently falsified the account books at his employer and vanished with all the cash he can get his hands on. The hobo’s fingerprints are taken — this is a new initiative instigated by Selby, and we get a semi-extended treatise on fingerprint classification from Bob Terry — and the body cremated at the request of the brother whose contact details are found on the body. The brother vanishes, the fingerprints don’t match any of the records (or indeed any of the other possible suspects), and the body’s identity is confirmed as readily as it is refuted by people who knew the man it might have been. Add in a stolen car, a murdered bank manager, the vanishing wife of the man suspected of the theft, and her suspicious ex-husband and, as Selby himself says, “It’s a whole series of suspicious circumstances pointing towards some crime which seems to have been covered up so completely we can’t find out much about it”.

Dude, the inside of Gardner’s head must have been a fascinating place. This was one of five books he published in 1940, including one of my favourite Cool and Lam novels Gold Comes in Bricks, and as well as a staggeringly complex piece of puzzle plotting that is resolved with a simplicity so beautiful you have to kick yourself for not seeing it (though, in fairness, there’s a lack of particular clue at the key point…) he also writes sentences like…

Civilisation and irrigation had pushed the desert far back from Phoenix, but at night, after the people were asleep, the desert reclaimed its own. The calm silence, the dry cold which sucked warmth from the body along with humidity, the steady unblinking splendor of the stars, were all the heritage of the desert.

He is supported as much as he is cajoled by Sheriff Rex Brandon and reporter-cum-love interest Sylvia Martin who walks the perfect line between sympathy and bullishness, responding when Selby attempts to shield her from harm in the closing stages with the perfect riposte “Get back of you nothing, you big egg…I’m a reporter. Move over so I can see!”. It is the relationship of this triumvirate that really makes these books for me, Brandon and Martin both liking Selby personally and respecting him professionally while also trying to negotiate for him the political arena in which he at times seems a layman.

He is supported as much as he is cajoled by Sheriff Rex Brandon and reporter-cum-love interest Sylvia Martin who walks the perfect line between sympathy and bullishness, responding when Selby attempts to shield her from harm in the closing stages with the perfect riposte “Get back of you nothing, you big egg…I’m a reporter. Move over so I can see!”. It is the relationship of this triumvirate that really makes these books for me, Brandon and Martin both liking Selby personally and respecting him professionally while also trying to negotiate for him the political arena in which he at times seems a layman.

I’m going to have to make a proper effort to get started on this series during the summer. I try to read at least a couple of Gardner books every year and I’ve only managed one up to now in 2018. You manage to make the characters sound very appealing so I’m bumping the Selby books up the list

LikeLike

I think I’m going to just put all Gardner’s books on permanent loop now. The Masons were far and away the larger proportion of what I had read, purely on account of how many there are, but I’ll get a few more years out of Selby and Cool & Lam and then get back to Perry, Della, Paul, and the gang…

LikeLike

I have similar feelings about Gardner’s work to those I have about Stout’s. OK, we don’t learn all that much about Perry, Della and Drake – Stout “fleshes out” the brownstone residents better in this regard – but I like being around the characters and spending time in their company, which is an important feature of good writing as far as I’m concerned.

LikeLike

Yeah, actually Gardner and Stout make a great comparison. I prefer the stories Gardner told, but they’re both hugely important in the genre and struggle to get the recognition they deserve for work done in expanding and popularising the crime story. Someone better read than I in both could do a much deeper comparison, but even at surface level they overlap in so many ways.

LikeLike

Gardner was the better plotter, by some considerable distance, but I would have said Stout was the more accomplished writer of character.

That comparison idea is a project I’d love to see someone take on, bu it would be a significant undertaking.

LikeLike

Okay, let’s spam Noah with this idea until he relents….

LikeLike

Gardner was the better plotter, by some considerable distance, but I would have said Stout was the more accomplished writer of character.

That’s a pretty fair summation. Both delightfully entertaining writers. And both still somewhat underrated (at least in comparison to the ludicrously overrated Crime Queens).

LikeLike

I will have to see if the Selby series is available through my library and check it out. I certainly enjoyed my first taste of Gardner’s writing so if you feel that these are better stories then that bodes well.

LikeLike

He’s been pretty regularly in print and I’m reasonably sure Noah put something up a while ago about a chunk of Masons being reprinted…so I reckon you’ll be able to track a few down via libraries. He’s a great writer, a great plotter, and manages to work in some superb character stuff as well.

It’s both a shame and a benefit that there’s no accepted “best” book of his, because I think this has contributed to his lack of acknowledgement in the genre, but it also means there’s the chance to pick up most of his stuff with no preconceptions and be delightfully surprised. Win/win!!

LikeLike

I am sure that I will be able to – a recent reprint run always helps. Your observation about how not having a best book can be an obstacle is interesting – I will have to give it some more thought.

LikeLike

I do think authors who don’t have a totemic work or three are much easier to get into, and someone you’re much more likely to persevere with. Seeing told “X is so-and-so’s best book” and the finding it average is a sure-fire way to lose enthusiasm for an author. Being told “Eh, they’re generally pretty good, pick one and see how you go” tends to encourage more stickability, I feel.

LikeLike

That makes sense to me. I think a related issue is that culturally we are often more aware of the twists in those totemic works too which means that they perhaps don’t surprise modern readers the way they did the contemporary audience.

LikeLike

I consider myself very lucky that I got to read a lot of Christie in complete ignorance of what was “good” and “bad” — think I got to enjoy them on my own terms, and was able to get much more out of the perceived weaker titles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the only one of the D.A. books that I haven’t read, so I really must make an effort to find a copy…

LikeLike

It’s a good one, though I think some of the later books contain more…let’s say surprising plots. But the simplicity of this when you realise what’s happened is something that Carr would’ve delighted to conjure up (and he would’ve put the telltale clue in, too!).

LikeLike

I can find almost all the Perry mason books but not any Cool & Lam or Doug Selby on my kindle. Apparently, the murder room ebooks of the DA series were not released everywhere. 😦

LikeLike

Yeah, the one drawback to ebooks is their territorial (un)availability. I have fever dreams in which Carr’s entire catalogue is eventually republished but released only in ebook and everywhere except for the UK. Thankfully you have plenty of Mason to keep you going (and, again, this is an advantage of here being no acknowledged “best books” — so many great stories there you still have the chance to discover!).

LikeLike

I’ve found a lot of Gardner’s books at charity book fairs and secondhand dealers. The Perry Mason books are the easiest to find, of course, but I’ve picked up a number of the Cool and Lamb books and a couple of D.A. titles as well. eBay would be another good place to find them!

LikeLike

I started with Gardner in much the same way, though there were often sizable gaps between finding books and I would find and read them hilariously out of order (not fatal, of course). This is part of why I’ve started Selby and will then do Bertha and Donald in order, just to get a general idea f the development of those series. Alas, the whole of ESG’s output in order would be too great a strain on my reading life and/or bank balance… 🙂

LikeLike