Ramble House

#69: Death’s Mannikins, a.k.a. The Dolls of Death (1937) by Max Afford

An isolated ancestral home ruled over by an eccentric patriarch with a keen interest in esoterica and a private museum of medieval weapons, into which an eager young man is brought by an acquaintance only for murder to insinuate its way among the denizens…yup, John Dickson Carr’s The Bowstring Murders (1933) certainly is a classic of the genre. What’s that you say? Death’s Mannikins? Oh, wow, uh, this is awkward. Okay, let’s start again: an isolated ancestral home ruled over by an eccentric patriarch with a keen interest in esoterica and a private museum of medieval weapons, into which an eager young man is brought by an acquaintance only for murder to insinuate its way among the denizens…yeah, no, there’s no getting away from those similarities. And, y’know what? I only bring it up because there’s more than a touch of Carr about this, Afford’s second Jeffery Blackburn novel, and that’s really not a bad thing.

An isolated ancestral home ruled over by an eccentric patriarch with a keen interest in esoterica and a private museum of medieval weapons, into which an eager young man is brought by an acquaintance only for murder to insinuate its way among the denizens…yup, John Dickson Carr’s The Bowstring Murders (1933) certainly is a classic of the genre. What’s that you say? Death’s Mannikins? Oh, wow, uh, this is awkward. Okay, let’s start again: an isolated ancestral home ruled over by an eccentric patriarch with a keen interest in esoterica and a private museum of medieval weapons, into which an eager young man is brought by an acquaintance only for murder to insinuate its way among the denizens…yeah, no, there’s no getting away from those similarities. And, y’know what? I only bring it up because there’s more than a touch of Carr about this, Afford’s second Jeffery Blackburn novel, and that’s really not a bad thing.

I mean, take the following:

It was as though the second tragedy acted as sudden leaping flames under a simmering pot. The scalding, seething flux exploded and boiled over, galvanizing each person under that roof into an insane panic that throbbed and hummed and zoomed from cellar to tower with the horrible impotence of a monstrous and unclean bluebottle trapped against a window.

Continue reading

#61: The Footprints of Satan (1950) by Norman Berrow

Lacking as I do the talent to devise my own fictional impossible crime and solution, I take refuge in those authors who have done it time and again to such success. The Footprints of Satan, my second Norman Berrow novel after the delightful surprise of The Bishop’s Sword, goes one even better: far from simply devising his own impossibility, he takes an unexplained one from real life, turns it to his own fictional purposes and then explains it away beautifully. Both the foreword and the plot here make reference to an incident from 1855 and reported in no less august a publication than The Times in which a trail of hoof-marks appeared in the snow as if from a cloven-footed creature walking on its hind legs.

Lacking as I do the talent to devise my own fictional impossible crime and solution, I take refuge in those authors who have done it time and again to such success. The Footprints of Satan, my second Norman Berrow novel after the delightful surprise of The Bishop’s Sword, goes one even better: far from simply devising his own impossibility, he takes an unexplained one from real life, turns it to his own fictional purposes and then explains it away beautifully. Both the foreword and the plot here make reference to an incident from 1855 and reported in no less august a publication than The Times in which a trail of hoof-marks appeared in the snow as if from a cloven-footed creature walking on its hind legs.

Continue reading

#49: The Talkative Policeman (1936) by Rupert Penny

Aaah, Christmas. A time for cheer, goodwill to all men, on-trend ironic jumpers and spending time with the people you love. Look around the crime fiction blogosphere and these loved ones include a tremendous number of murderers, victims, stooges, detectives and classic authors, and so for me the time is ripe for a return to my overriding obsessions: this week it’s Ernest Basil Charles Thornett’s turn as his debut under the guise of Rupert Penny with The Talkative Policeman. And of course it’s a return to impossible crimes after a couple of weeks away with what the synopsis calls a “longer-than-usual impossible mystery,” and since Penny has written a couple of absolute doozys in this vein an extra bt of content is only to be a cause for celebration. Clap hands. Settle in. Let’s go.

Aaah, Christmas. A time for cheer, goodwill to all men, on-trend ironic jumpers and spending time with the people you love. Look around the crime fiction blogosphere and these loved ones include a tremendous number of murderers, victims, stooges, detectives and classic authors, and so for me the time is ripe for a return to my overriding obsessions: this week it’s Ernest Basil Charles Thornett’s turn as his debut under the guise of Rupert Penny with The Talkative Policeman. And of course it’s a return to impossible crimes after a couple of weeks away with what the synopsis calls a “longer-than-usual impossible mystery,” and since Penny has written a couple of absolute doozys in this vein an extra bt of content is only to be a cause for celebration. Clap hands. Settle in. Let’s go.

This was the second Penny I read after the wonderful Sealed Room Murder, and it’s fair to say that despite loving that I approached his debut with a little caution. The puzzle plot is not something one typically excels at upon first attempt, so expecting the same level of craft from this tale of a blameless rural vicar found battered over the head in the woodland near his home would probably be unwise. And while it may be true that the plot doesn’t quite hold up – we’ll get to that – there is enough quality here to see the germ of the author Penny would become. Continue reading

#43: Owl of Darkness, a.k.a. Fly by Night (1942) by Max Afford

Regular readers of this blog – hello, Mum – will be aware of how much I appreciate die-hard devotees like Fender Tucker and Tom and Enid Schantz, whose (respectively) Ramble House and Rue Morgue Press imprints have for years been keeping the kind of classics everyone had long forgotten about in print just for the love of them. I won’t condescend to imply that everything they publish is of equal quality, but some of it is more equal than others and they have jointly brought some absolute delights to my attention. Unfortunately the latter’s Smallbone Deceased (1950) by Michael Gilbert proved not to be my kind of thing and so I couldn’t really review it having not read it, but it does give me a chance to talk about Max Afford’s Owl of Darkness which is published by the former and I read in those bleak and hazy dark days I now think of as ‘pre-blog’.

Regular readers of this blog – hello, Mum – will be aware of how much I appreciate die-hard devotees like Fender Tucker and Tom and Enid Schantz, whose (respectively) Ramble House and Rue Morgue Press imprints have for years been keeping the kind of classics everyone had long forgotten about in print just for the love of them. I won’t condescend to imply that everything they publish is of equal quality, but some of it is more equal than others and they have jointly brought some absolute delights to my attention. Unfortunately the latter’s Smallbone Deceased (1950) by Michael Gilbert proved not to be my kind of thing and so I couldn’t really review it having not read it, but it does give me a chance to talk about Max Afford’s Owl of Darkness which is published by the former and I read in those bleak and hazy dark days I now think of as ‘pre-blog’.

#37: The Bishop’s Sword (1948) by Norman Berrow

It is due to experiences akin to that of reading The Bishop’s Sword – a euphemism of a title if ever there was one, though here referring to a literal sword once owned by a bishop – that I started this blog in the first place. Picking up a book with very little to go on (a cursory, and then slightly more thorough, search online revealed not a single review of this anywhere) and having it turn out to be an absolute joy is the kind of thing I have to share with someone though, while in no way dismissing the many fine qualities that they do possess, not the kind of thing my friends necessarily share my enthusiasm for. And so I throw this to the interwebs, that you may be a way of enabling me to feel that someone who might be intrigued is going to share in this, and frankly you’re on to a corker if you decide to partake. You are, of course, most welcome. Continue reading

It is due to experiences akin to that of reading The Bishop’s Sword – a euphemism of a title if ever there was one, though here referring to a literal sword once owned by a bishop – that I started this blog in the first place. Picking up a book with very little to go on (a cursory, and then slightly more thorough, search online revealed not a single review of this anywhere) and having it turn out to be an absolute joy is the kind of thing I have to share with someone though, while in no way dismissing the many fine qualities that they do possess, not the kind of thing my friends necessarily share my enthusiasm for. And so I throw this to the interwebs, that you may be a way of enabling me to feel that someone who might be intrigued is going to share in this, and frankly you’re on to a corker if you decide to partake. You are, of course, most welcome. Continue reading

#23: Death Leaves No Card (1939) by Miles Burton

A door is broken down, a dead body is found behind it; there is no other exit from the room, but equally no sign of a weapon nor any evidence of suicide…these classic staples of the archetypal impossible murder are put on page one of Miles Burton’s Death Leaves No Card. Added to this is the puzzle of precisely how the deceased came to decease, as there is sign of neither violence nor harm on the body, no evidence of poison or gassing, and, this being the late 1930s, the house is not yet fitted with electricity so it can’t have been electrocution. It may or may not be a locked room, since the window might or might not have been open, but the unclear nature of the death definitely makes it an impossible crime in my eyes. Either way, cue sensible Inspector Henry Arnold.

A door is broken down, a dead body is found behind it; there is no other exit from the room, but equally no sign of a weapon nor any evidence of suicide…these classic staples of the archetypal impossible murder are put on page one of Miles Burton’s Death Leaves No Card. Added to this is the puzzle of precisely how the deceased came to decease, as there is sign of neither violence nor harm on the body, no evidence of poison or gassing, and, this being the late 1930s, the house is not yet fitted with electricity so it can’t have been electrocution. It may or may not be a locked room, since the window might or might not have been open, but the unclear nature of the death definitely makes it an impossible crime in my eyes. Either way, cue sensible Inspector Henry Arnold.

Continue reading

#20: Policeman’s Evidence (1938) by Rupert Penny

If you’ve never bought a house on the questionable basis of a 300-year-old document implying the miserly, hunchbacked previous owner might possibly have hidden a marvellous treasure trove somewhere thereabouts, well, you must not be independently wealthy. You’ll also, then, have never invited various family and hangers-on down to said house to engage in a search invoking the types of ciphers that would give Dan Brown’s Robert Langdon a damp counterpane and – consequently – never had to deal with the aftermath of a suicide-that’s-probably-murder in a locked, treble-bolted and exitless room.

If you’ve never bought a house on the questionable basis of a 300-year-old document implying the miserly, hunchbacked previous owner might possibly have hidden a marvellous treasure trove somewhere thereabouts, well, you must not be independently wealthy. You’ll also, then, have never invited various family and hangers-on down to said house to engage in a search invoking the types of ciphers that would give Dan Brown’s Robert Langdon a damp counterpane and – consequently – never had to deal with the aftermath of a suicide-that’s-probably-murder in a locked, treble-bolted and exitless room.

Thankfully for you, however, all these things happened to Major Francis Adair, and Tony Purdon and Chief-Inspector Edward Beale were on hand to relay it, albeit through the pen of Rupert Penny, the pseudonym of Ernest Basil Charles Thornett (who would go on to publish one book under another nom de plume, Martin Tanner – are you keeping up?). Policeman’s Evidence is the third of Penny’s novels, available thanks to the continued superlative efforts of Fender Tucker’s Ramble House, and it’s probably the most classically-constructed of his books that I’ve read, as involved and well-planned a puzzle as you’ll find from this era. An attack on a member of the household hints that a disgruntled ex-employee might be lurking suspiciously and with harmful intent, plenty of possibly-blameless-but-possibly-significant interactions occur, and everything is laid out with scrupulous fairness in time for the challenge to the reader to solve the puzzle before Beale lays his hand on the perpetrator.

Continue reading

#11: Five to Try – Non-Carr impossible murders

Simple criteria: novels only, readily available, not conceived in the fertile ground of John Dickson Carr’s imagination. I’ve also restricted the impossible crime to being the comission of the murder – people stabbed or shot while alone in a room, effectively – more to help reduce the possible contenders than anything else. Several stone cold classics are absent through the inclusion of other invisible events but that’s a future list (or five…).

Carr – doyen of the impossible crime, responsible for more brilliant work in this subgenre than any other three authors combined – will eventually get his own list (or five…), I just have to figure out how to separate them out; restricting it to five novels was hard enough for this list, but if you’re looking to get started in locked room murders these would be my suggestions:

Continue reading

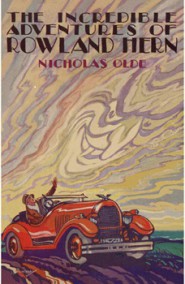

#10: The Incredible Adventures of Rowland Hern [ss] (1928) by Nicholas Olde (Part 2 of 2)

Credit: Facsimile Dust Jackets

I am from a televisual generation and so struggle to comprehend the power radio held in its pomp – people actually believing that Orson Welles’ radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds was genuinely detailing an alien invasion of Earth, for instance. So, to me, the idea of presenting the haunting of a Spooky Old House as a radio show seems a bit…pointless. Nevertheless, Jack Hartley and his BBC radio chums descend upon Cold Stairs, the ancestral home of Sir John Harman (5 bed, 2 bath., stunning aspect in own woodland), to record ghostly goings on and bumps in the night with the intention of making a broadcast of it. Or that should really be ‘bumping offs in the night’ as some poor soul is murdered by the evil spirit that resides in the vicinity – the same spirit that shocked his housekeeper’s son so badly he fell down the stairs and crippled himself – and then it turns out that Harman’s introverted, reserved niece has been communing with something calling itself the King of the Forest, and that’s really the beginning of everyone’s problems.

I am from a televisual generation and so struggle to comprehend the power radio held in its pomp – people actually believing that Orson Welles’ radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds was genuinely detailing an alien invasion of Earth, for instance. So, to me, the idea of presenting the haunting of a Spooky Old House as a radio show seems a bit…pointless. Nevertheless, Jack Hartley and his BBC radio chums descend upon Cold Stairs, the ancestral home of Sir John Harman (5 bed, 2 bath., stunning aspect in own woodland), to record ghostly goings on and bumps in the night with the intention of making a broadcast of it. Or that should really be ‘bumping offs in the night’ as some poor soul is murdered by the evil spirit that resides in the vicinity – the same spirit that shocked his housekeeper’s son so badly he fell down the stairs and crippled himself – and then it turns out that Harman’s introverted, reserved niece has been communing with something calling itself the King of the Forest, and that’s really the beginning of everyone’s problems.