![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

If the year 2020 will be remembered for anything, it will be that I bought a set of 18 J.J. Connington novels on eBay and started my way through them. Of those 18, only A Minor Operation (1937) — Connington’s sixteenth novel and the eleventh to feature Chief Constable Sir Clinton Driffield — showed any signs of being read, implying that this one book alone was bad enough for the seller to completely eradicate Connington from their shelves. Well, having finally reached this accurséd title, I really enjoyed it — finding it one of the strongest of Alfred Stewart’s books yet, only lacking in the final stretch with a too-casual reveal of our killer and a motive that’s perhaps a little too complex to really hit home.

Reviews

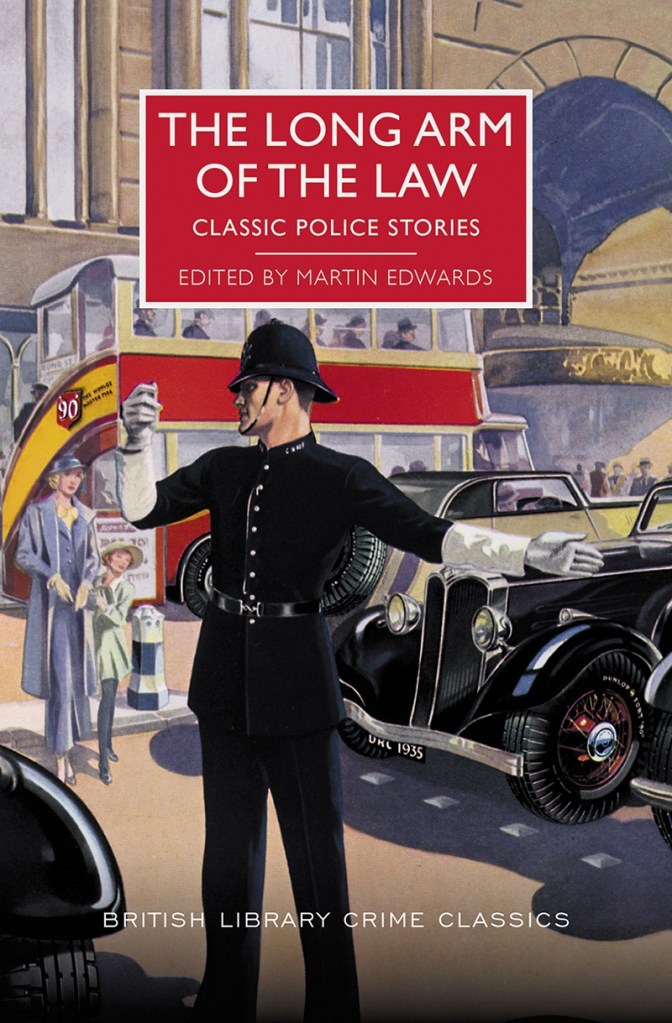

#1318: “That’s the worst of these detective stories; every criminal knows that trick.” – The Long Arm of the Law [ss] (2017) ed. Martin Edwards

An earlier British Library Crime Classics short story collection today, with The Long Arm of the Law [ss] (2017) featuring 15 stories of professional police selected by the hugely knowledgeable Martin Edwards.

Continue reading#1317: Murder for Cash, a.k.a. The Fatal .45 (1938) by James Ronald

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Crazy to think that even a couple of years ago the works of James Ronald were so wildly unavailable that it seemed we’d never know exactly what, of the fair amount he wrote, was crime fiction and what came from other, equally profitable, genres. Then Chris Verner and Moonstone Press entered the arena, and Ronald’s criminous oeuvre has become readily available for sensible money. And so Murder for Cash, a.k.a The Fatal .45 (1938), a pulpy tale that comes nowhere near the level of Ronald’s best work — Murder in the Family (1936), They Can’t Hang Me (1938) — but nevertheless warrants examination by anyone curious about what this all-but-forgotten author has done to garner such attention in the modern day.

#1314: Cold Blood (1952) by Leo Bruce

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Leo Bruce’s eighth and final novel in which Sergeant William Beef sallies forth into polite company to batter them with blunt questions hiding a brilliant mind, Cold Blood (1952) is a strong effort that marks a distinct improvement from preceding title, the over-long and frankly tedious Neck and Neck (1951). It’s the battering to death of a wealthy landowner which concerns us here, with Beef brought in by Cosmo Ducrow’s surviving family to counter the evidence piling up against the dead man’s nephew, Rudolf. But, the more Beef looks, the blacker the case against Rudolf becomes…so is this the final convention-busting solution Bruce has for us at the cap of this series, or is something more subtle going on?

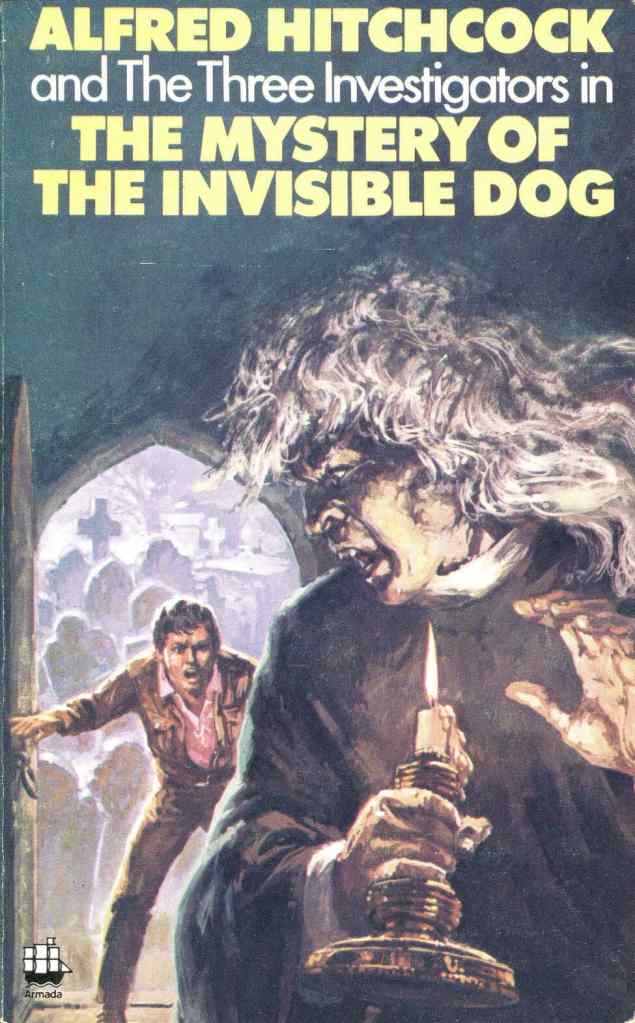

#1312: Curious Incidents in the Night-Time in The Mystery of the Invisible Dog (1975) by M.V. Carey

Mary Virginia Carey was not, it seems, scared of a little velitation in her stewardship of The Three Investigators.

Continue reading#1311: Fear Comes to Chalfont (1942) by Freeman Wills Crofts

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Your typical Freeman Wills Crofts protagonist — fallen on hard times, usually following the death of a loved one — young widow Julia Langley enters into a marriage of convenience with solicitor Richard Elton. He will provide for her daughter Mollie, and she will run his house, Chalfont, as hostess for social events that singularly fail to win his unprepossessing personality the acceptance he so craves. And so, Julia falls in love with wealthy novelist Frank Cox, throwing a wrench into the works of her agreeable if not desirable arrangement, and before long someone in the Elton ménage is found murdered and the various secrets in the household start to creep out.

#1309: Murderers Make Mistakes – Sudden Death Aplenty in Six Against the Yard [ss] (1936)

Today is the tenth Bodies from the Library Conference, at which, until other considerations intervened, I was due to present on the topic of inverted mysteries. And you can bet I would at some point have talked about Six Against the Yard (1936), in which six crime writers put their ‘perfect murder’ on paper and ex-CID man Superintendent Cornish picked holes in their plans.

Continue reading#1308: You’d Look Better as a Ghost (2023) by Joanna Wallace

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Like The Serial Killers’ Club (2006) by Jeff Povey and the Darkly Dreaming Dexter (2004-15) series by Jeff Lindsay, Joanna Wallace’s debut You’d Look Better as a Ghost (2023) takes on the challenge of seeing the world through a serial killer’s eyes. Wallace, though, takes the far harder route of not trying to justify her killer’s murderous urges by having them only kill ‘bad people’, and instead invites you to spend nearly 400 pages with Claire, who is unhinged enough to murder a man who accidentally emailed her incorrect information, and who blithely admits that she “like[s] to peel the skin off queue-jumpers”. It shouldn’t work. But, thanks in no small way to some pitch-black humour, boy, does it.

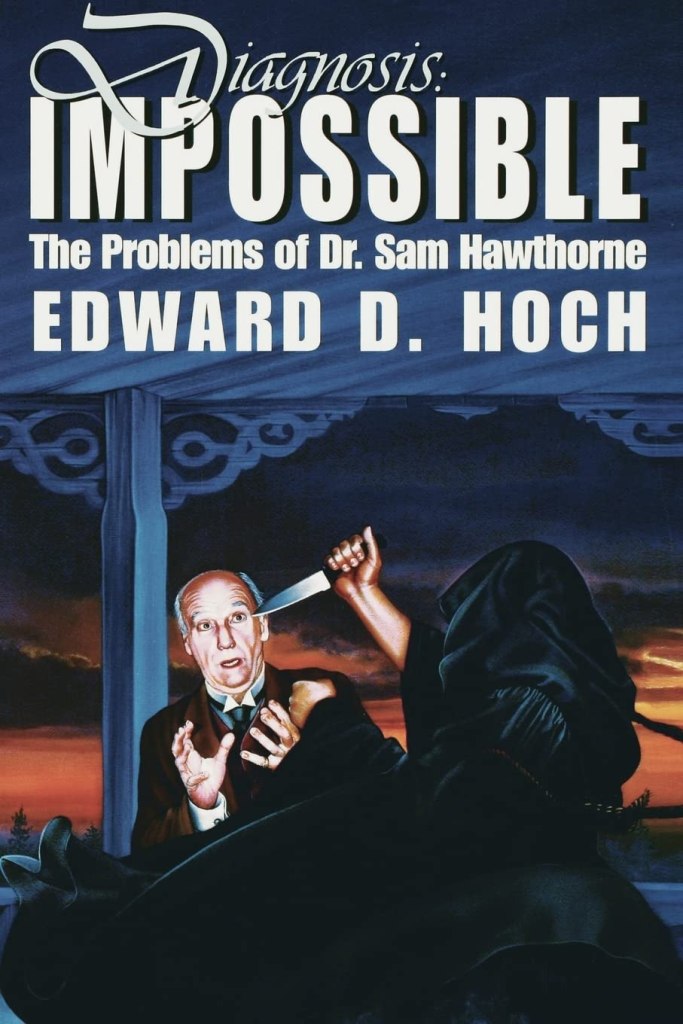

#1306: “Ain’t nothin’ like this ever happened in Northmont afore!” – Diagnosis: Impossible: The Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne [ss] (2000) by Edward D. Hoch

You don’t write as much as Edward D. Hoch without hitting the bull’s-eye a few times, so I’m finally doing what I should have done all along and starting the Dr. Sam Hawthorne series from the beginning, with this first collection, Diagnosis: Impossible (2000), a tranche of 12 stories initially published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine between 1974 and 1978.

Continue reading