![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’ll level with you: I’d been kind of dreading having to reread Case without a Corpse (1937), Leo Bruce’s second novel to feature the blunt-but-far-from-dense Sergeant William Beef. Memory told me that the novel was over-long, with a large proportion of it spent on an almost entirely pointless amount of investigation that any sensible reader would know is wasted effort because (rot13 for spoilers, if you’ve never read a book before) boivbhfyl Orrs unf gb or gur bar gb cebivqr gur pbeerpg fbyhgvba ng gur raq. And in rereading it for the first time in about 15 years I’ve discovered that, once again, my memory has been a little unkind, and the book holds up far better than anticipated.

Reviews

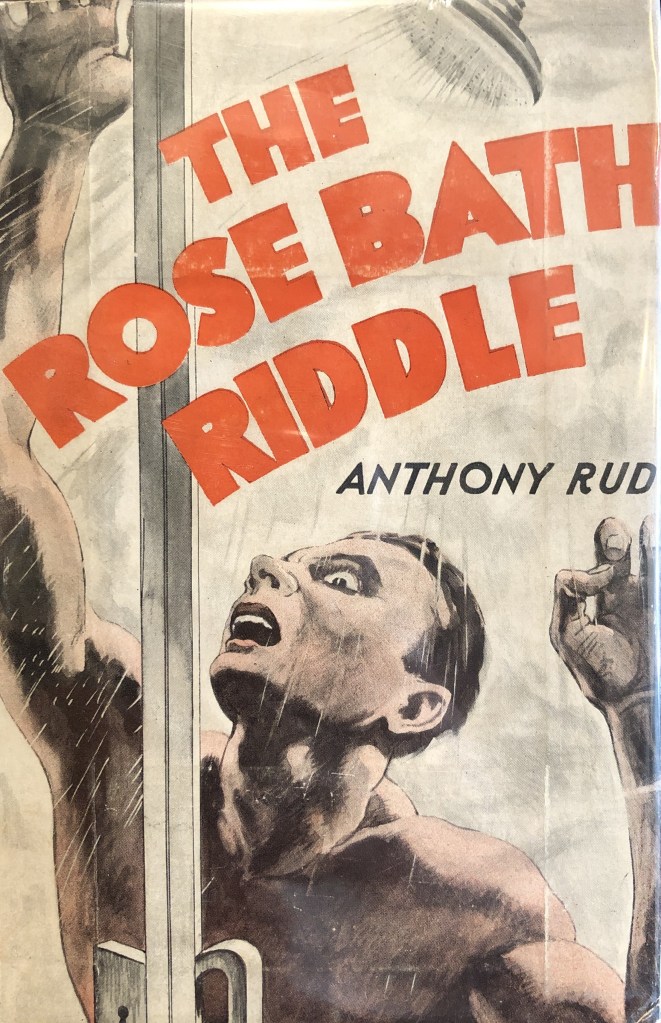

#1354: “A number of those in this house will never see tomorrow’s sun!” – The Rose Bath Riddle (1933) by Anthony Rud

#1353: When Rogues Fall Out, a.k.a. Dr. Thorndyke’s Discovery (1932) by R. Austin Freeman

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Once again, now for a third time, I have been misled by these House of Stratus editions about the nature of a book by R. Austin Freeman. The cover of When Rogue’s Fall Out, a.k.a. Dr. Thorndyke’s Discovery (1932) promises “Three Books in One, starring Dr. Thorndyke”, leading me to surmise that these were three novellas. Not so. As it happens, Book 1 – The Three Rogues, Book 2 – Inspector Badger Deceased, and Book 3 – The Missing Collector are simply parts of one novel-length story, and I approached the end of The Three Rogues very confused about the apparent lack of impending conclusion and the distinct absence of Thorndyke from its pages.

#1350: Cat and Mouse (1950) by Christianna Brand

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

With the British Library having cracked the decades-old problem of getting Christianna Brand republished — they’ve now put out six of her novels, with a seventh, her debut Death in High Heels (1941), to follow in November — it’s wonderful to dive into Cat and Mouse (1950) and find something decidedly uncommon that speaks of an author wanting to challenge herself after penning some of the best small-cast, twist-ending novels in the genre. The focus on an almost Gothic level of mood and suspense here puts one in mind of a similar attempt in Telefair, a.k.a. Yesterday’s Murder (1942) by Craig Rice; but Brand wins, because she also remembered to include a plot.

#1347: The Secret of the Downs (1939) by Walter S. Masterman

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When young Frank Conway returns to his hotel on the edge of the South Downs one evening in a distracted frame of mind, none of the other denizens of the Fernbank think much of it. His request for an audience with various people are rejected in the rush for dinner and when, over that same meal, Conway dies in an agonising and protracted manner, many of the people present begin to regret their thoughtlessness. Conway’s final movements then fall under the remit of local man Inspector Baines, and, with the dead man’s sister also in attendance, two parallel investigations are run…but which will bear fruit first? And how does the sighting of a ghastly half man, half monster on the Downs tie into events?

#1344: The Spiral Staircase, a.k.a. Some Must Watch (1933) by Ethel Lina White

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Thanks to the ongoing efforts of the wonderful British Library Crime Classics range, I have an improving impression of the work of Ethel Lina White — the excellent ‘Water Running Out’ (1927) was included in the Crimes of Cymru [ss] (2023) collection and The Wheel Spins (1936) was a superb little thriller which did well with its highly appealing setup. All of which saw me snap up a copy of The Spiral Staircase, a.k.a. Some Must Watch (1933) when one drifted into my orbit, and, well, this shows again how effective White can be with a small number of people in a restricted setting…even if, at times, she’d rather have them get together and talk over old ground instead of getting on with the story.

#1341: Miss Winter in the Library with a Knife (2025) by Martin Edwards

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“[H]ow stressful can this game really be? A few nights in a peaceful hamlet at Christmas, trying to make sense of a puzzle? What could possibly go wrong?”. Well, an unseasonally heavy snowfall could maroon everyone, and then a murderer could start picking off the isolated denizens of the peaceful hamlet of Midwinter. But, if they can survive the slaughter, the six people who have been invited by the Midwinter Trust to take part in the competition, called Miss Winter in the Library with a Knife, are unlikely to want to leave because the prize they can win is…well it’s fabulous, isn’t it? It must be. Although, now you come to mention it, what is the prize?

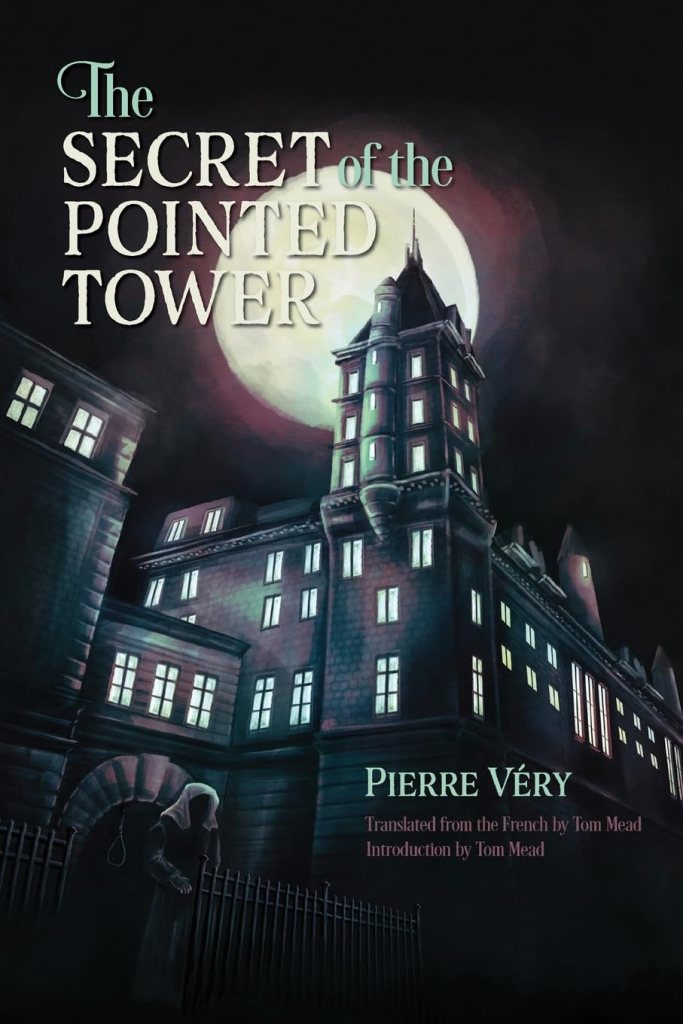

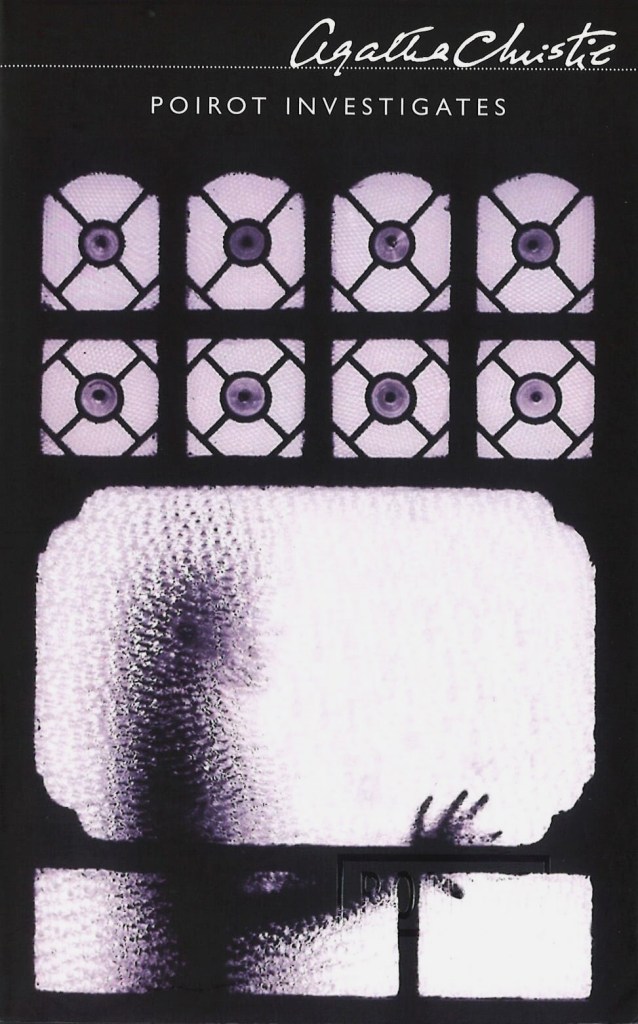

#1339: “With method and logic one can accomplish anything!” – Poirot Investigates [ss] (1924) by Agatha Christie

Eleven cases from the early career of the World’s Favourite Golden Age Sleuth, Poirot Investigates (1923) offers a chance to revisit a collection I’ve not read in, oh, twenty years. Lovely stuff.

Continue reading#1338: The Black Angel (1943) by Cornell Woolrich

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

It’s been over two years since I reviewed any Cornell Woolrich, which seems incredible when you consider how completely I loved his work when he first started appearing on The Invisible Event. But, well, behind the scenes I’ve struggled through some of his stuff — the doom-drenched but ooooooverlong The Black Alibi (1942) and the somewhat tedious, Francis Nevins-edited Night and Fear [ss] (2004) collection — and lost the name of action, so to speak. But you can’t keep a good fan down, and so it’s back to the novels and The Black Angel (1943), which interestingly finds a new way to explore themes and approaches that would seem to recur throughout Woolrich’s oeuvre.