My first two excursions into the 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] (1977) anthology haven’t exactly been roaring successes. Might some actual detective work find things more to my liking?

Let’s find out, as this week we read:

Analytical Detective: ‘The Ceaseless Stone’ (1975) by Avram Davidson

The Story

Someone is making gold rings, but they’re…too good? Like, there’s too much gold in them? And where did the gold come from? So Dr. Englebert Eszterhazy — “Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Philosophy, Doctor of Jurisprudence, Doctor of Science, and Doctor of Literature” — sets out to find where the gold is coming from. Why? Honestly, this story is such a mess, I do not care.

The Genre Trappings

In the introduction, mention is made of Edgar Allan Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin, whose “amazing deductive powers provided the prototype for all subsequent analytical detectives”. What this story fails to recognise about the analytical detective is that there should be some, y’know, analysis and detection — Dupin and Holmes were largely unknowable early on, but they at least went to the effort of explaining their (yes, often dodgy) reasoning…something you’d expect Davidson to be familiar with given that he had before penning this this co-written two novels in the Ellery Queen corpus with Fred Dannay.

What seems to happen here, however, is that Davidson sticks entirely to the concept of the Great Detective being unknowable, so that we’re never clear on how he reaches his conclusions…and, indeed, seems to stumble onto almost all of them by chance. So, after an undeniably atmospheric setup…

Annually the gold leaf of [the clock’s] numerals was renewed and refreshed, and the numerals were Roman, not as any deliberate archaicism, but because no other numerals were known thereabouts when it was made; the “Arabic” numbers, in their slow progression out of India through Persia into Turkey, had nowhere reached that part of Europe when the Clock was made…

…and much consternation about the provenance of the gold being used to make inferior-quality rings which are being sold for cut-down prices to impressionable young men — which they care about because, I guess, taxation…? — Eszterhazy goes for a walk, finds some sailors, sits down with them, eventually gets round to noticing that one of them doesn’t have a pierced ear only to be told that it’s the ear on the side not facing Eszterhazty that’s been pierced and the earring going into it is in the pocket of the boy with the new piercing, only for it to turn out that the piercing is the same gold that has been causing consternation, only for the man he bought it from to have used an obscure phrase the boy remembers, only for that to be a reference to a massively obscure work, only for that to apparently somehow tell Eszterhazy that the man making the gold is a baker so he goes to a bakery and finds him.

Like, at no point does any of this come from actual analysis or detection.

The sailors he sits down with, for instance, seem to be the first ones he comes across, and even then it’s not like he notices the boy’s pierced ear, or that the new piercing stands out or even has the cheap gold on display. Then the boy happens to remember a phrase which immediately leads Eszterhazy to the obscure book…and how that leads him to the bakery I don’t even want to go back and find out. It’s a short chain at the best of times, and the most optimistic perspective on this finds serendipity in every link and crevice.

And then the motive for the whole thing — spoilers, but, honestly, it’s not worth the effort of reading — is that the guy making the gold wants to raise enough money to work on finding “the elixir of life” and so was selling it cheaply to make money…so why not sell it at the normal asking price, pay the taxes, and still make the money you need faster? You ever get that feeling when you read something bad that it only seems bad because you’re the idiot and you’ve missed something? But now you know it’s bad, and you’re a little bit angry, you don’t want to waste any more time on reading it a second time because, damn, it’s not exactly proven itself to be worth the effort? Yeah, that’s ‘The Ceaseless Stone’.

I also have no idea why it’s called ‘The Ceaseless Stone’. Some internet searching tells me that the phrase crops up in some writings about Sisyphus…but there’s nothing remotely Sisyphean about this, so, honestly, I will have to leave that mystery unsolved. Maybe it’s in there and I missed it, but I do not care. That’s the almost spiritual level of indifference this story has provoked in me; I don’t even care enough to write a more detailed examination of just how little I care. I’m not even going to finish this next sentence with a full stop — look at me, I’m a madman

So, well, in terms of genre trappings of the analytical detective, this demonstrates only the principles as understood by someone who has no concept of what detection is. Just knowing stuff and being in the right place with the right people by sheer happenstance is not detection, and if you hadn’t told me up front that this was an example of a crossover mystery then I would never have made the connection myself. But I’ve gone on long enough. This story does not warrant this degree of analysis.

What Does SF Add?

This being in a very loosely-realised SF universe honestly just allows the fictional obscure text to exist so that Eszterhazy can go right there and so onto the malefactor. A dim sense of governance concerning the sale of items and thus having to pay tax on them lingers in the background — there’s a king or an emperor or a grand poobah or something — but, honestly, this is a story about a guy taking a walk, remembering a book, and calling in at a bakery.

And, look, there’s one nice piece of genre crossover…

The brothers were dark, the boy was fair, and Eszterhazy had met all three in connection with a singularly mysterious affair involving an enormous rodent of Indonesian origin.

…but I think even that would have gone over my head had I not been told to think of Sherlock Holmes in the introduction. I really do get the impression that some stories are included in this collection because all the SF crowd in the 1970s were big mates and didn’t have the heart to tell each other when they thought something one of them wrote was shit, y’know? Still, it’s Jack Vance next, and he at least wrote a couple of detective novels, so we remain hopeful…

~

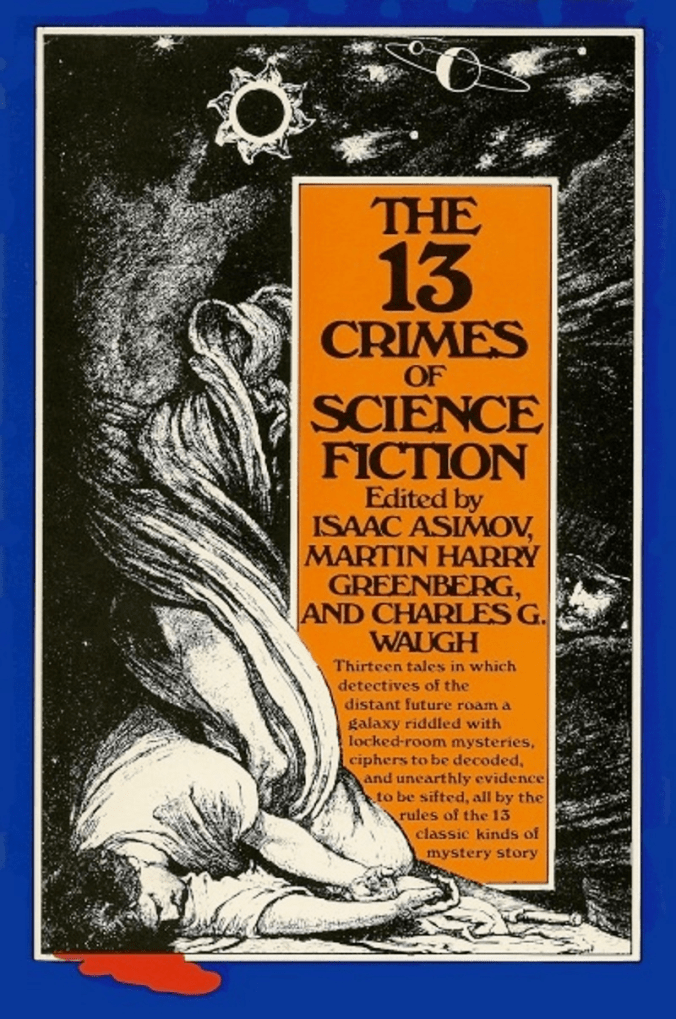

The 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] edited by Isaac Asimov, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh:

- ‘The Detweiler Boy’ (1977) by Tom Reamy

- ‘The Ipswich Phial’ (1976) by Randall Garrett

- ‘Second Game’ (1958) by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean

- ‘The Ceaseless Stone’ (1975) by Avram Davidson

- ‘Coup de Grace’ (1958) by Jack Vance

- ‘The Green Car’ (1957) by William F. Temple

- ‘War Game’ (1959) by Philip K. Dick

- ‘The Singing Bell’ (1954) by Isaac Asimov

- ‘ARM’ (1975) by Larry Niven

- ‘Mouthpiece’ (1974) by Edward Wellen

- ‘Time Exposures’ (1971) by Wilson Tucker

- ‘How-2’ (1954) by Clifford Simak

- ‘Time in Advance’ (1956) by William Tenn