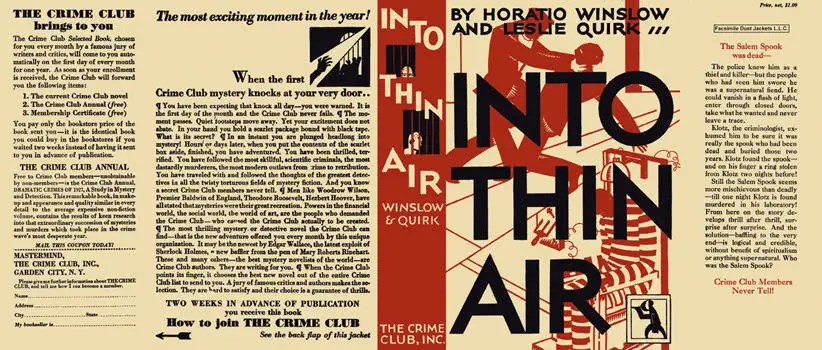

The Roland Lacourbe-curated list of 100 impossible crime novels has held quite a sway in my reading life. Hell, I got one of the titles on it reprinted purely so I could read it myself. Until John Pugmire’s death, Locked Room International did a stalwart job bringing many of the foreign-language titles into English…but still some books on the list seemed frustratingly out of reach, no more so than Into Thin Air (1928) by Horatio Winslow and Leslie Quirk.

Behold, then, the wonderful classic-era-mystery blogging community which I have talked about before, from which stepped forward a reader of this blog who had a copy of Into Thin Air and wasn’t necessarily all that married to the idea of holding onto it forever. Could, they suggested, a trade be arranged? And it could! And so, shortly thereafter, I was in possession of a physical copy of a book that I honestly never believed I would ever have. Life, sometimes it…it does the thing, y’know? So let’s talk about the book, which is a hoot.

Set in Salem in 1927, the plot here is actually pretty loose, so forgive me while I do a bad job of recounting it.

A thief — and possibly murderer…? — known only as the Salem Spook has been captured, and the prologue contains clippings of newspaper articles about his various amazing feats: flying out a window, disappearing in a dead-end alley, escaping from prison when surrounded by guards, and, eventually, perishing in a train crash only to be buried in a pauper’s grave. A couple of months later, an ex-magician once known as the Great Galeoto is giving a demonstration on the various means that spiritualists (I omit the adjective “fraudulent” as self-evident) use to con their marks. To this demonstration arrives Dr. Klotz, head of the Department of Criminology at, er, a possibly unspecified university, and while he is there — for some reason his presence is seen as disrupting the event, despite it apparently being in keeping with his own interests — a note is received in impossible circumstances that make him believe that the Salem Spook is, at the very moment, visiting at his home.

From here, the books is a pell-mell race from impossible event to impossible event: the vanishing of the visitor from a room with no exit, the appearance of an object in a disinterred grave, a séance with various spectres, and a whole heap of ghostly sightings and manifestations that seem to hint that the Salem Spook does indeed walk, float, and vanish at will among us. The plot largely consists of our narrator, Criminology expert Professor Alden T. ‘Nolly’ Nollins, a colleague of Klotz’s, ricocheting from one event to the next with a small surrounding cloud of various players, witnessing seemingly impossible happenings, and then staggering away to wonder precisely who could be responsible…or if there is an eldritch force behind it all. Then one of the cast is found shot in a locked room, with a group of students chasing the glowing presence of the Salem Spook up to the roof where he floats through a skylight and disappears…and so suddenly things are a little more serious.

And, yes, I’m aware that tells you quite a lot and not very much at all. The book is sort of like that, with the same air of high energy menace and confoundment that marks out Rim of the Pit (1944) by Hake Talbot. And fans of that work by Talbot will find much to enjoy in Winslow and Quirk’s undertaking.

So, where to start? Firstly, the atmosphere of this tale is very neatly managed, occasional bursts of loquacity that interrupt the hell-for-leather narrative proving shiversome…

The breeze came back with a playmate of fog, to form a gossamer mist, pale with moonlight, that rose from the grass: serried ranks of a phantom army. The wraiths hovered about us, touching with clammy fingers; they glided to tombstones and enveloped them; they danced fantastically about the ragged bush beyond the grave; they floated between us and the moon and dimmed its rays.

…or adding a febrile air to a séance that Nolly has attended with his scepticism in full show (“[E]ven I, sneerer and skeptic, felt the spirit world descend and close about us.”). It helps, too, that the cast, while largely people by broad Types, has room for those who acknowledge that, yes, mediums use fraudulent methods, but possibly only because sometimes they have to when their genuine talents don’t come through for an expectant audience (incidentally, a similar idea is expressed in About the Murder of a Startled Lady (1935) by Anthony Abbot). Interesting to see this explored not just by the characters (“I detected a wistful longing about her eyes…a desire to believe that in all the haystack there might be some needle of truth.”) but by the authors themselves, with one element of the plot — not a major one, don’t dismay — being left as if, yeah, that was ghosts all along.

The only characters to really register are Klotz — all swapped consonants and undefinable European accent and expressions — and Galeoto. And this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, since both are easily big enough for a novel of their own, so trying to crowd in too many Personalities around them would rob the book of its wonderful magnetism. Both fall under suspicion, it’s their area of expertise, after all, and both have strong motives for achieving the effects witnessed by so many herein: Galeoto’s career ended in disgrace, and he is now a “pitiful, shabby husk” of the master he once was, and Klotz recently failed to solve a crime and so might be “creat[ing] mysteries for the pleasure and honor of solving them” in order to enhance his tarnished reputation. These titans clash again and again, and a book that focussed on them more as antagonists might have been more commercially successful, since they’re both great fun.

Just past the halfway point there is a treatise of sorts on detective stories, giving the impression that this is going to be one, but please remember that this is America in the 1920s, a geography and era that was not big on minutiae. The explanations when they come — and the last 60-odd pages comprise the various demystifying treatises — are pretty much plucked out of the ipsedixitism playbook, and seek to explain away everything about the Salem Spook…and, well, don’t.

Some of it is, I’ll be honest, a little disappointing, but after such a cavalcade of insanity as this there is going to be a faux pas or two. Some of the explanations of events we have merely heard about and not seen are especially weak, with characters believing it but nothing in their experience making this reader feel there was a ring of veracity about it. At times it does feel like the authors going ‘Look, they think it’s true, so you must, too…!’ and these are easily the shakiest parts of the whole edifice. Mind you, the flip-side of this argument is that it would be entirely against the, ahem, spirit of the book to expect everything to be tied up with mechanical tightness, and so allow a little wiggle room and you’ll be fine.

The majority of the events we have seen, then, are similarly explained as if it’s just accepted that it would work, rather than giving me anything that convinced me for certain. I would, I can’t deny, have liked at least one thing to be a little more nailed on than it proves here — think of the clever physical reasoning that mostly concludes of Rim of the Pit — but, honestly, I really enjoyed seeing this picked apart. For a novel to be attempting something so wild in the 1920s is no small achievement, and Winslow and Quirk deserve huge kudos for tying together this list of undoable things and making it so very entertaining along the way.

Into Thin Air, then, is not a lost classic, and I can almost understand why no-one has reprinted it because it would prove a little too nebulous for the general reader. Fans of the Golden Age, especially those of us well-submerged in the complexities of the puzzle plot and impossible crime, will find much here to glory in, and it is to be lamented that no-one has taken up the mantle of Locked Room International, since the book is almost tailor-made for that enterprise: by a fan, for the fans. I’m half-tempted to see if I can convince some small press to put out a limited run of this, because a bunch of you out there would get a real kick out of it, and, after his excellent presentation at Bodies from the Library the other year, Tom Mead has already done some great research that would make for a fascinating introduction.

I am, then, delighted to have had a chance to read this, and pass on once again my thanks to the very kind reader who put this into my hands; we’re a wonderful community, and it remains a delight to be a part of this. Now if someone wants to lend me a copy of Withered Murder (1955) by A. & P. Shaffer, I could finally tick off all the (available-in-English) books on the Lacourbe list and do an analysis of the whole shebang…

~

See also

TomCat @ Beneath the Stains of Time: So, while not anywhere near as good as [John Dickson] Carr, [Hake] Talbot or even [Clayton] Rawson, the avalanche of impossibilities remain consistent from the prologue to the very ending. Not one of them is truly mind-blowing when explained, but neither do they deliver a crushing blow of disappointment.