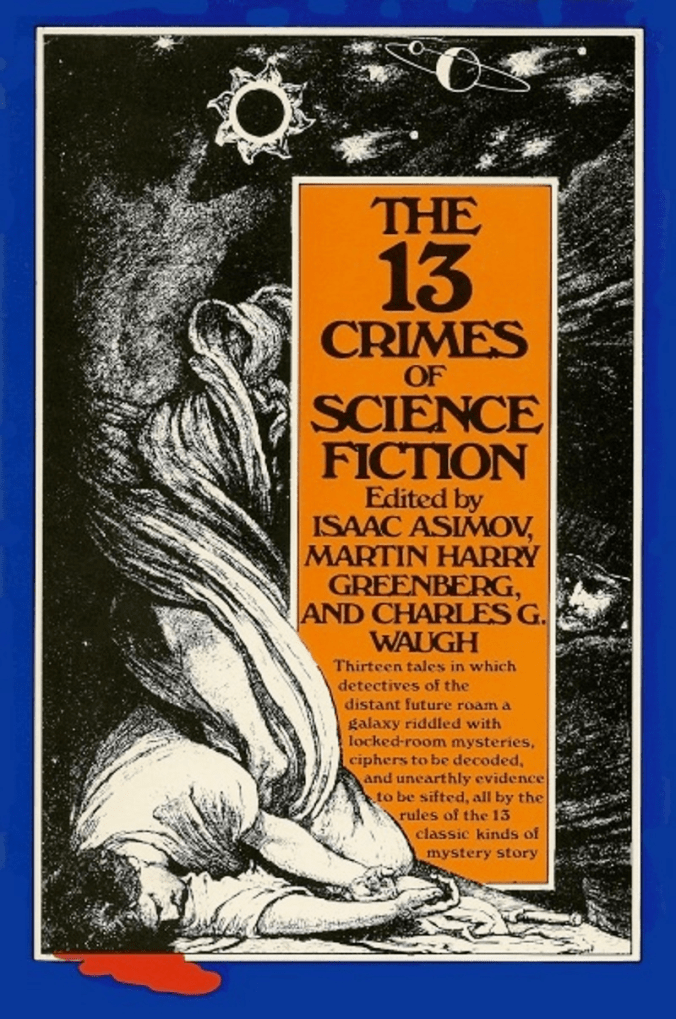

A second delve into The 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] (1979), as I explore the possibilities of another crossover mystery.

This week:

Spy Story: ‘Second Game’ (1958) by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean

The Story

Man has colonised the stars, with a galactic alliance known as The Ten Thousand Worlds. Yet, of those ten thousand, only one seems to hold out where overtures of peace and compatibility are made: the planet Velda. And so government agent Robert O. Lang is sent to Velda to blend in — no great difficulty, since the inhabitants appear human except for one, easily hidden, difference — and to capture the attention of those in power to see what may be done, and whether some negotiation or communication lines may be established.

The Genre Trappings

The miniature introduction to this story does well to acknowledge the scope of what has passed under the spy story banner over the decades, encompassing “John Buchan’s romantic idealism, Eric Ambler’s realism, Ian Fleming’s power fantasies, and John Le Carre’s views of systemic corruption”. And De Vet and MacLean seem to be aware of this scope and so lean into…all of it.

Lang starts of as a power fantasy type, playing the largely undescribed, chess-like Game which forms the core of society on Velda, “played from earliest childhood — [and is] in fact a vital aspect of their culture”. And, like James Bond, he’s amazing at it, beating first any arbitrary passer-by who’s willing to take up his challenge, then the more established practitioners, and, eventually, two of the planet’s great players. Lang is then immediately outed as a human and must go on the run, using his skill and spycraft against the Veldians in a gripping story that highlights the way an essential human savagery and ingenuity can overturn even the advantages of a society based from its earliest day in competition.

Oh, no, sorry, I got that wrong. Let’s try again.

Lang is then immediately outed as human, and lots and lots and lots and lots of long, tedious conversations are had, and then, fifty million pages later, it ends thinking it’s made some sort of intelligent Asimovian/Dickian point when in fact it’s just so. Damn. Tedious. God, this was boring.

As genre trappings go, this has very little. Lang is amazing, and all the women on Velda can’t help by be amazed by him and find him compelling, but since it’s the men who have the voluptuous bodies — I think, I had really lost interest by this point — there’s probably some sort of latent homosexual metaphor or something (I’m not saying it’s deliberate). He’s told he’ll be put to death and reacts stoically — which is to say, he doesn’t react at all — and then lots of conversations are had over and over and he eventually has a final conversation where it turns out he was right all along.

To be honest, this so completely bears out my experience of reading Eric Ambler to date that between them these two piece of fiction have put me off the notion of approaching anything described using the words “spy story” ever again.

What Does SF Add?

The SF trappings here are so dense — new world, odd practices, strange names, all of it merely hinted at rather than discussed — that I’m amazed the editors of this collection thought there was any space left in the narrative for any of the spy story tropes that make it apparently qualify. Last week, ‘The Detweiler Boy’ (1977) by Tom Reamy arguably needed its hardboiled tropes to sell you something familiar and then sucker you with a truly left-field conclusion. This…this just wants to spend a very long time describing a journey in a carriage.

So where it was previously the case that SF did indeed add something to the story-form, here it’s more a case of the story not even existing without the SF elements, since what remains is barely anything else. And to think they could have had something like ‘Paycheck’ (1953) by Philip K. Dick in here instead — which, no, also isn’t a spy story, but at least vaguely leans into systemic corruption, utilises some ingenuity, and has a pitch-dark twist at the end.

God, I wish I hadn’t read this.

~

The 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] edited by Isaac Asimov, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh:

- ‘The Detweiler Boy’ (1977) by Tom Reamy

- ‘The Ipswich Phial’ (1976) by Randall Garrett

- ‘Second Game’ (1958) by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean

- ‘The Ceaseless Stone’ (1975) by Avram Davidson

- ‘Coup de Grace’ (1958) by Jack Vance

- ‘The Green Car’ (1957) by William F. Temple

- ‘War Game’ (1959) by Philip K. Dick

- ‘The Singing Bell’ (1954) by Isaac Asimov

- ‘ARM’ (1975) by Larry Niven

- ‘Mouthpiece’ (1974) by Edward Wellen

- ‘Time Exposures’ (1971) by Wilson Tucker

- ‘How-2’ (1954) by Clifford Simak

- ‘Time in Advance’ (1956) by William Tenn