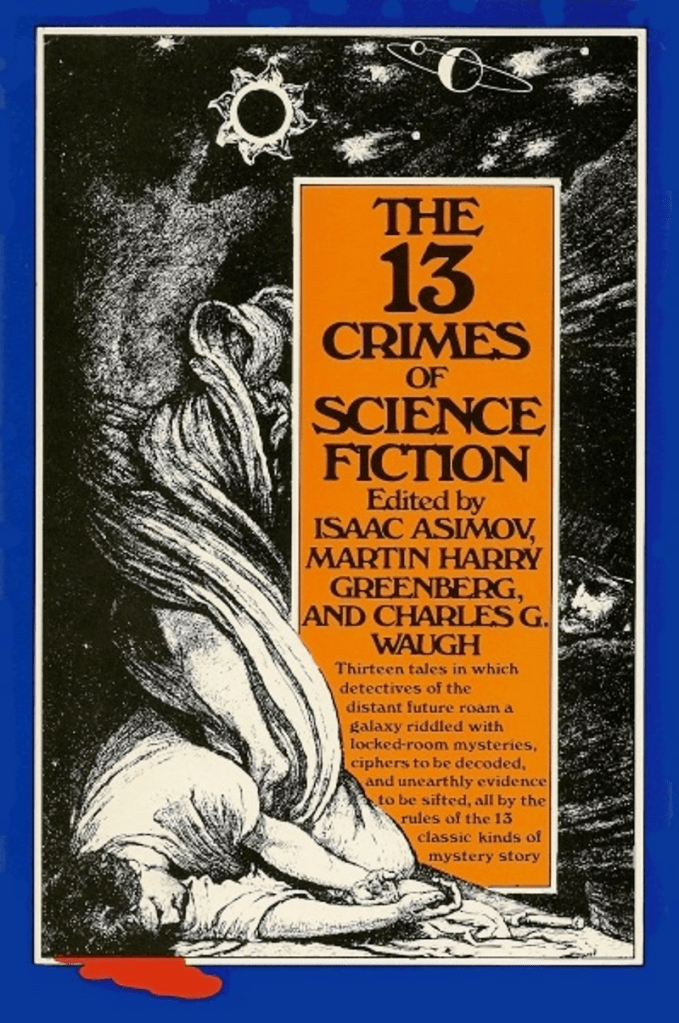

I am a fan of a good crossover mystery, in which the tenets of crime and detection are placed into a science fiction/Fantasy milieu. So when I heard of a collection called The 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] (1979), you’re darn tootin’ it was only a matter of time before I got to it.

Edited by Isaac Asimov, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh, this collection professes to contain the thirteen types of crime fiction story, each utilising the trappings of SF in its telling. So, for Tuesdays over a few months in the neat year or two, I’m going to take 12 stories in turn (I’m excluding ‘The Ipswich Phial’ (1976) by Randall Garrett as I’m already looking at the Lord Darcy stories in another undertaking) and discuss them.

This week:

Hard-Boiled Detective: ‘The Detweiler Boy’ (1977) by Tom Reamy

The Story

Receiving a call from an acquaintance staying at a — what else? — sleazy hotel, P.I. Bertram ‘Bert’ Mallory arrives to find his connection, who had, of course, been unwilling to share his news over the phone (“[He] saw too many old private-eye movies on the late show.”), bloodily murdered. It seems that the dead man might have wanted to talk to Bert about twenty-something, hunchbacked Andrew Detweiler, another of the hotel’s residents, who checked out almost at the instant that the victim was being murdered.

Mallory tries to track down the Detweiler boy, and finds a pattern emerging: he is always staying nearby when a violent death occurs, and then moves on. He can’t be a murderer — some of the deaths are clearly suicide, and, besides, Detweiler always seems to have an alibi or be in company at the time of expiration — but how to explain the pattern?

The Genre Trappings

There’s a lovely little introduction to this story by, one presumes, some combination of the editors, in which the concept of the hardboiled detective is briefly outlined, paying homage to Dashiell Hammett, Carroll John Daly, and Keith Laumer, and talking about Tom Reamy’s “[Raymond] Chandlerlike skill with analogy and description”. Crucially, what this revels in is the seamy underside of life, from the hotels and motels Mallory visits…

Her tenants were the losers habitating that rotting section of the Boulevard east of the Hollywood Freeway.

…to the lousy area of town he can afford to keep offices in…

This section of the Boulevard wasn’t rotting yet, but it wouldn’t be long.

…to salacious hints at Mallory’s own sexual existence and that of the wider, smuttier world in which he lives, all the seedier from being right at the cusp of the golden world represented by Hollywood, with its drugs (“Sounds to me like he was hurtin’ for a fix.”), faded, forgotten, never-were actresses, and movie theatres showing “an X-rated double feature”. It’s a world full of young men bargaining with their bodies for a shot at stardom, and suffused with the tragic air of Mallory knowing that everything they want is already well out of reach.

So, yes, of course our down-on-his-luck private detective, undertaking tawdry divorce cases and minor diversions despite the need to keep financially fluid, is cynical…

Friday, the 22nd, the same day Detweiler checked in the Brewster, a two-year-old boy had fallen on an upturned rake in his backyard on Larchemont — only eight or ten blocks from where I lived on Beachwood. And a couple of Chicano kids had had a knife fight behind Hollywood High. One was dead and the other was in jail. Ah, machismo!

…and of course there’s an element of deprecatory self-loathing in his dealings with his matronly, efficient secretary (“Would Sam Spade go looking for a French poodle named Gwendolyn?”). Honestly, if you didn’t know this was in a collection of SF storied, you’d be given no reason to suspect it, right down to Mallory tracking Detweiler down to a — where else? — sleazy, run-down motel and investigating his room to find a dearth of personal belongings as telling as the transient life he seems to be deliberately leaving (“All of it together would barely fill a shoebox.”).

That talent of Chandleresque analogy comes in handy on a couple of occasions…

Her hair was the color of tarnished copper, and the fire-engine-red lipstick was painted far past her thin lips. Her watery eyes peered at me through a Lone Ranger mask of Maybelline on a plaster-white face.

…and, just as I was wondering if this was merely a set of straight detective stories written by normally SF-adjacent writers, man, things get fuckin’ weird.

What Does SF Add?

In part, my interest in exploring this collection came from something Asimov says in his introduction to the volume: basically, that if you take any normal story and put it in a weird setting — cowboys doing a cattle drive, but with eight-legged cattle across the surface of Mars — then it becomes an SF story. So, to what extent does each of these tales need its SF trappings to exist as it does?

Trust me, ‘The Detweiler Boy’ needs its SF trappings.

I mean, they come the hell out of nowhere — it’s like the start of one story has been grafted on to the end of something else — but a lack of preparation isn’t necessarily unexpected in this subgenre. I’m no fan of the hardboiled detective, but I was enjoying ticking off the tropes talked about above…and then, holy hell, it very much becomes the sort of thing I wish I hadn’t read, and I don’t know how to talk about it without spoiling it for you…but then I also cannot recommend that you, dear reader, seek this out for yourself.

It’s telling that the eventual direction of this is shocking even to the hard-bitten, disaffected Mallory, and that’s arguably why it’s told in this milieu: the resolution contrasts so shockingly with the familiar beats hit up to that point, and it really rocks you back on your heels. Were this placed in a purely SF setting, with unusual politics or transport, weird food, strange beings, and all the other trappings of the purely fantastical, it would be less affecting, and that’s sort of genius in its own twisted way — the crime story doesn’t need the imagination-pushing, boundary-challenging SF in order to work, it’s the SF ending which requires the hidebound, familiar nature of the hardboiled detective and all his associated baggage in order to hit as hard as it does.

It is to be hoped, however, that later stories integrate their genre boundaries a little more smoothly.

~

The 13 Crimes of Science Fiction [ss] edited by Isaac Asimov, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh:

- ‘The Detweiler Boy’ (1977) by Tom Reamy

- ‘The Ipswich Phial’ (1976) by Randall Garrett

- ‘Second Game’ (1958) by Charles V. De Vet and Katherine MacLean

- ‘The Ceaseless Stone’ (1975) by Avram Davidson

- ‘Coup de Grace’ (1958) by Jack Vance

- ‘The Green Car’ (1957) by William F. Temple

- ‘War Game’ (1959) by Philip K. Dick

- ‘The Singing Bell’ (1954) by Isaac Asimov

- ‘ARM’ (1975) by Larry Niven

- ‘Mouthpiece’ (1974) by Edward Wellen

- ‘Time Exposures’ (1971) by Wilson Tucker

- ‘How-2’ (1954) by Clifford Simak

- ‘Time in Advance’ (1956) by William Tenn