![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

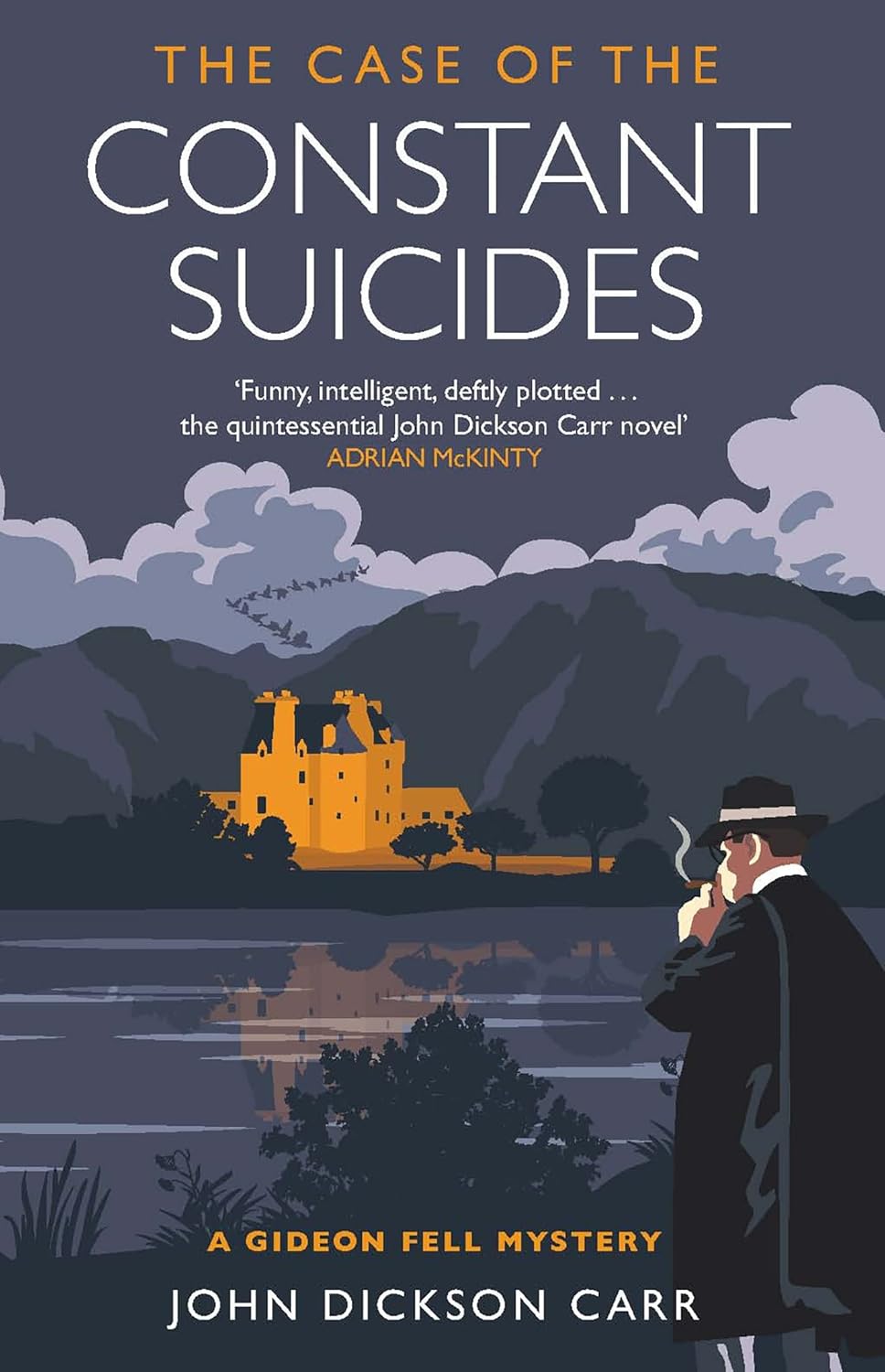

A man sleeping alone in a bolted room, five storeys up in the tower attached to his grand old house, wakes in the night and hurls himself out of the window to his death. Refusing to believe in spooks, spectres, and eldritch terrors, the man’s son determines to sleep in the room as well, and similarly hurls himself from the sole window while alone and the door is again bolted. And if that setup doesn’t entice you to read The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941), John Dickson Carr’s lucky thirteenth long form case for Dr. Gideon Fell, then, well, I don’t know how else to entice you in. It was this book that convinced me Carr was going to be my flavour of jam years ago, and I returned to it with great eagerness.

Of course, the book is not quite as I remembered it: the opening on the train is still good fun, with our bland-man-who-will-find-love Dr. Alan Campbell reliving an academic debate he is having in the newspapers with another expert about the Duchess of Cleveland, but there’s a lot more meeting people in Scotland on our way to the Castle of Shira on the isolated Loch Fyne. It turns out we’re about a quarter of the way in before that impossible death of Duncan Campbell is related, and the second plunge from the tower occurs well past the halfway point. It still nips along, though, and proves to be plenty of fun in the telling.

Carr seems to have hit here a lovely balance between the atmospheric…

Southwards, above spiky pines, you could see far away the great castle of Argyll, with the four great towers whose roofs change colour when it rains. Beyond would be the estate office, once the court house, where James Stewart, guardian of Allan Breck Stewart, had been tried and condemned for the Appin murder. All the earth was rich and breathing with names, with songs, with traditions, with superstitions.

…and broad comedy (a man getting stabbed in the arse, or having two buckets of water emptied over his head), rooted is some good character notes (“You know, I can’t decide whether I like that old woman or whether I’d like to murder her…”) and a solid mystery which, if it doesn’t quite exploit its setting, at least stirs in a ghost with only half a face and some lovely, mist-drenched scenes of chaos and ill reason.

You could not get away from anything that chose to pursue you here.

The unflappable Dr. Fell, then, who has been “haunted and pursued by such matters”, gets to the bottom of those plunges very quickly indeed, and the reader isn’t left in the dark for very long, with the mystery of what chased those men out of that window tied up much earlier than I recalled…and incorrectly, too. One wonders if this was the book that Isaac Asimov was referring to when he said that Carr’s lack of awareness in certain matters saw a plot “reduced…to a shambles”, and it’s amusing, too, to open the book and see the early line “Errors are errors, whoever writes them” lurking as if in early apology. Still, the principle holds even if the details aren’t precise.

And the plot has some good foundation for confoundment, too, such as our dead man taking out £35,000 worth of insurance policies on his life and so being unlikely to kill himself knowing there was a suicide clause in every policy. It’s not the sort of rippling, seething problem that confronts his players in the masterpieces Carr penned, but as an isolated little tale with its compact cast in this forgotten corner of the country it’s a nice little problem for an insurance man to be understandably reticent to pay out on, and for everyone else to be cudgelling their brains about how to convince him otherwise.

I can fault the book really in two areas: first the killer is barely in it and so unlikely to be landed on fairly by any reader, and secondly that the key piece of convincing information comes in the form of a photograph. Both are rather too key to be avoided altogether, and knocked my enjoyment of this down a star from what I remembered when it was 50% of the Carr I had read. In its favour, however, is a pleasing portrait of how the Second World War has affected even these isolated corners (“You should have remembered how [the roads] are patrolled late at night…”) and a sort of reminder of how much the war had worn on its contemporary audience:

It was only the first of September, and the heavy raiding of London had not yet begun. We were very young in those days. An air-raid alert meant merely inconvenience, with perhaps one lone raider droning somewhere, and no barrage.

One also takes comfort in knowing that the state of public transport remains about the same 80 years later (“The 9.15 train from Glasgow to Euston slid into Euston only four hours late…”).

I enjoyed this return, then, and would still hold up The Case of the Constant Suicides as a good place to start on your Carr journey. The Polygon Books reprint is a lovely artefact and, with some wonderful Carr novels also readily available, I am very envious of anyone who gets to experience him as a new prospect in this day and age. What a wonderful reading life you have ahead of you.

It was this book too that really hooked me onto Carr – following Death In Box C and The Hollow Man. It’s a bundle of fun, even if I’m pretty sure the murder method is utter nonsense.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s a shame Carr feels the need to go into the science, because he could get away with, well, something less scientific and we’d all be happy. Ho-hum.

Still, a highly enjoyable book, and a great place to encounter some of Carr’s trickery for an early or new reader.

LikeLike

It’s funny, but your comment about the murderer being obscure has made me realise how little I remember about this one. A quick check and it was one of the first blog reads so due a revisit, methinks

LikeLike

Good lord, that’s nearly 15 years ago. Funny how time flies, eh?

LikeLike

Yeah, I’m old…

LikeLike

For me, it was this and Hag’s Nook that hooked me in to Carr. I haven’t read this in ages, though. A revisit is due, perhaps 😏

LikeLike

Hag’s Nook was certainly an early one for me, because it was Hag’s Nook, Constant Suicides, Judas Window, and Peacock Feather that were published by Rue Morgue and therefore readily available at the time. I can understand how that title in particular might get its hooks into one — and thankfully Carr more than fulfilled the promise of both these titles in his work elsewhere.

Happy rereading when you get to it 🙂

LikeLike

You young fellows and your Rue Morgue Press! For me, it was Signet, and so my first titles were The Arabian Nights Murders, The Mad Hatter Mystery – and Constant Suicides! I remember absolutely nothing about it, except I believe I laughed and enjoyed it. Really, Jim, this should’ve been a book club selection for this year!!!

LikeLike

And think of the young types getting into Carr now — especially in the, er, wake of Wake Up Dead Man. Look at the sheer range of stuff available from the BLCC, the American Mystery Classics, these Polygon reprints…man, what a time to discover GAD and its associated joys.

LikeLike

Strangely enough, I remember the romance of this one more than the murder — though I do recall the basics of the impossibility. There’s a moment on that train when they look out the window and see their own reflections that stays with me to this very day. Even seeing this on my shelf brings up that moment in my mind. It’s rare for a Carr book.

LikeLike

It’s actually quite a good romance, given that it takes place in a GAD novel. There’s a little more to it than some books, where it can sometimes feel like the male lead and female lead turn to each other on the final page and go “Marriage?” just to appease…someone.

LikeLike

There’s a nice passage in Dorothy L Sayers’s Have His Carcase which is clearly poking fun at bad detective story romances:

LikeLike

Slightly ironic, given that Harriet and Peter have one of the most self-satisfied romances in all of fiction, but Sayers was rarely wrong when she turned her attention to things in this way.

LikeLike

I’m going to politely ignore that first part lol* and just say that I for sure think that one of Sayers’s big strengths was describing in a compelling way how the world and people work. Sometimes a bit of her… extremely specific worldview infects it but even when it does she’s brilliantly good at describing it convincingly. (I have some really big issues with parts of Murder Must Advertise that people seem to love for some reason; the overall book is fun but IMO the first really significant sign of Sayers’s entrenchment in her Views.)

*All I’ll say here is that a) for sure Peter and Harriet can be an acquired taste and b) in real life, many romances are as meaningful to the people within them as they feel self-satisfied and goopy to the people outside them, and for Sayers to capture that with these particular characters in Gaudy Night actually worked very well for me. I write and think a LOT about the Wimsey books but probably best not here lol

LikeLike

Pretty much everyone is more of a fan of Peter and Harriet than I am, so take my opinions with a pinch of salt 🙂

LikeLike

I think that what makes the romance in this one work is that there’s no attempt to make it “realistic”- it’s pure screwball and doesn’t try to pretend anything different, so it works on its own terms. So like other such romances it ends up being silly, but it’s MEANT to be silly so we’re happy with it.

LikeLike

…which is part of why I enjoy the Justuses in Craig Rice’s work so much. The knockabout nature of their interactions doesn’t ring true for a second, and yet it somehow makes their relationship at the middle of it all seem so much more worth investing in, for some reason.

LikeLike

Oooh yes, excellent connection, she’s so clearly also working within a screwball comedy framework there! I do get a bit tired of the Justuses when stretched across multiple books- there’s a reason why most 30s screwball comedies didn’t get sequels, because the dynamics of screwball don’t really stand up to deep relationship building*- and at some point one or the other of them will hit someone with the car while driving drunk. But she definitely understands the genre in each individual book.

*Nick and Nora Charles don’t count because they’re married already when we meet them, I’ve decided

LikeLike

Carr had basically the same romance plot in one of his short stories, with the two historians who are rivals. It was a good idea to use it in a novel as well.

LikeLike

Ooo, I don’t remember that one and so +may not have encountered it yet. It is a good romance, I agree — a rare thing indeed in GAD!

LikeLike

I read this 2 or 3 years ago; I mainly remember that I found the main impossibility of the eponymous constant suicides a bit disappointing, and the later impossibility, while somewhat technical, much more satisfying. I know it’s always been considered a classic Dr Fell but for me it gets overshadowed by the 3-book run that immediately followed it of The Seat of the Scornful, Till Death Do Us Part, and He Who Whispers.

LikeLike

Interestingly, my initial response was the other way round: the suicides were brilliant, and the technical explanation a little disappointing. With a second read, I think they’re all equally flawed, but then I suppose this was Carr’s thirty-fifth book in eleven years (!!!) and so he can be forgiven for resorting to some less-than-brilliant conceits at times.

And, yes, you’re quite right, the three Fell books that follow this are astonishing. Some authors would give a limb to write three books that good in an entire career.

LikeLike