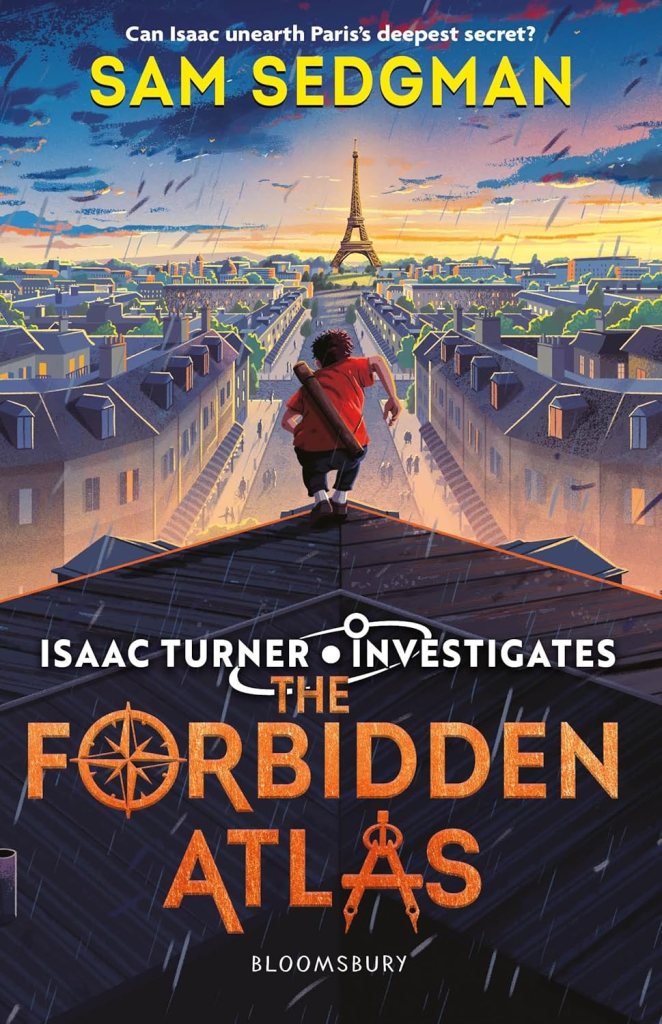

While I would have liked Sam Sedgman’s debut novel The Clockwork Conspiracy (2024) to be rather more clue-based, given his history in the juvenile mystery field, I nevertheless enjoyed its fast pace, high energy, interesting premise, and unusual settings, and so am back for its sequel, The Forbidden Atlas (2025).

This time around, given their — spoilers? — success in foiling the scheme in that first book, Isaac Turner and Hattie Bassala are in Paris to receive medals and congratulations from the International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Just as they take the stage, however, the lights go out, a shot is fired, and, in the ensuing commotion, they find themselves pursuing a suspect who vanishes in mildly-baffling circumstances.

Before long, the two friends have learned of a possibly-mythical treasure hidden around the time of the French Revolution, one which many people are still searching for today, and are engaged in a battle against an unseen foe who, once again, has a sinister and threatening myrmidon running around the city and encountering our intrepid protagonists at regular intervals. How do a series of graffiti tags tie into the mystery? Who or what is Mirage? And how does the gigantically rare map of Paris, the Laval Projection, apparently provide all the answers that Isaac, Hattie, and their unknown nemesis seek?

So, yes, this is once again a mystery-thriller more in the vein of The Da Vinci Code (2003) than any sort of detective novel, but it’s once again told with such verve and engaging energy that I ripped through it in very little time without really minding that most of the reasoning seemed to be people taking massive leaps and always being right. Sedgman really does write very well, his chapters flying past with superbly-paced revelations and plenty of intrigue that manages to also slip in a little edutainment along the way.

“I didn’t know France invented the Metric System,” said Isaac.

“But of course,” said Eveline. “Why do you think it works so well?”

We carom around Paris, learning a few interesting things along the way — trap streets, for one — and I particularly enjoyed that attention is paid to seemingly irrelevant matters (c.f. lighting a fire in a cave, establishing exactly what a metre is) in a way that speaks to a great consideration going into things behind the scenes.

I also particularly like that Sedgman has a good sense of his teenage protagonists as teenagers — taking a moment to reflect how out of the ordinary it feels to be unchaperoned in an unfamiliar city, for example, something which will really resonate with the intended audience of this book. There’s also a superb moment where, in the midst of all their adventuring, Isaac is genuinely terrified to have to continue further, and Hattie has to talk him out of his fear so that they’re able to continue (they’d be completely foxed if she wasn’t successful…), and it’s again a lovely choice to see these kids as kids who are in over their heads and having to learn and adapt, rather than simply having everything go to plan without so much as a turned hair.

So while it’s clear that Sedgman isn’t writing the sort of thing I’m after, it’s also worth acknowledging that what he is writing is well-explored, treats its intended audience respectfully, manages to maintain a fast pace without dropping into too many obvious info-dumps, and displays a freshness that feels telling in this crowded marketplace. Sure, it’s very much more James Bond, Jr. than Young Poirot, but as high-stakes adventuring that sees an Evil Plan scuppered by a couple of precocious young people it walks its fine line well and remains a blast in the process.

Next up for Isaac and Hattie is The Galileo Heist (2026), which will doubtless provide exactly the sort of experience I know I can turn to it for when I’m ready for some action alongside the cerebration I so crave!