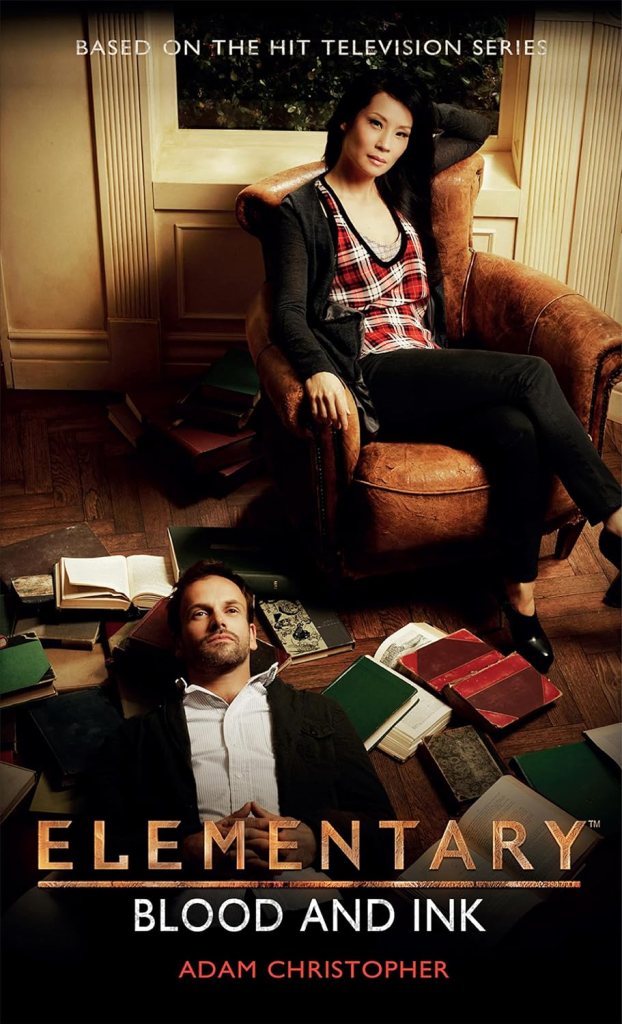

One of only a handful of tie-in novels I’ve read, Adam Christopher’s The Ghost Line (2015) did an excellent job of tapping into the feeling of Elementary (2012-19), the US TV version of the updating of Sherlock Holmes. And so to Christopher’s second and final novel for the series, Blood and Ink (2016), do we turn today.

The Ghost Line might have run out of plot in the final stretch, but Christopher did an excellent job of capturing the spirit of the show and, crucially, the characters of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Joan Watson as portrayed on-screen by Jonny Lee Miller and Lucy Liu respectively. So, with no extra seasons of the show apparently forthcoming — seriously, now, I would be so excited if they announced more Elementary — Blood and Ink is, perhaps, my final chance to bathe in the world of the show…before rewatching it, since I keep forgetting to cancel my Amazon Prime membership and might as well put that money to use.

So it’s a bit of a shame to report that, this time around, Christopher doesn’t quite do the sterling job he did in that first novelisation. The characters feel right, and the methods feel just about right — hacker collective Everyone really are an excellent way to get around the sheer profligacy of media these days, as you would need thousands of people poring over footage as Holmes asks them to do here — but the point the plot has reached at about the 90% mark is where most episodes of the show would be after 20 minutes, and, wow, does the lack of incident really show.

Called to the scene of a murder in a seedy hotel — the fact that Captain Gregson mentions it’s a stabbing is, apparently, enough to pique Holmes’s interest, even though there must be, what, hundreds of stabbing in New York every day — Holmes and Watson are greeted by the body of a man stabbed through the eye with an extremely valuable fountain pen and, given his position as the CFO of a hotshot financial services firm, plenty of private security in situ. And, now that I sit down to write this, I realise that practically nothing is done with the private security once the focus moves from this scene. It, like, never comes up again.

Additionally, when they go to the dead man’s highly-fashionable and very expensive apartment, it’s interesting that he seems to have no electronic records of anything, preferring to keep a paper diary, in which he writes with one of his Brobdingnagian collection of pens:

“With his expertise and experience as a security analyst, it seems Mr. Smythe had an aversion to technology, at least in his private life, and instead liked to do things the old-fashioned way.”

From here, a mysterious appointment sets us on the path of business guru-cum-snake-oil-salesman Dale Vanderpool, and from there…it just sort of circles around a lot, with some slow progress made via dodgy means (not once but twice do we rely on interpreting scenes reflected in windows), lip service paid to Holmes’s intelligence (the use of “trigonometry” is, of course, never explained), and the sort of obscured declaration that is common in the Holmes canon but gets frustrating when you realise that some of what you’re not told (“He drank his coffee back at the precinct with his left hand.”) would have worked on TV.

Very occasionally we get something that feels like this version of Sherlock Holmes being as intelligent as he can be, such as when reviewing the movement of the employees of that financial services firm — they all have trackers in their phones — he “identif[ies] two extra-marital affairs (one between two employees), one terminally ill close family member — possibly an aunt, although that was mere supposition — and an expensive addiction to champagne and a very particular kind of imported Turkish delight”. Elementary never traded too heavily in Holmes explaining his deductions, and I wasn’t really expecting it to be a feature of this, but it’s at least nice to see how the man’s intelligence can’t help but find patterns and explanations even when they’re not relevant to what he’s looking for.

[T]his was the moment Holmes strived for. To solve the case, catch the perpetrator, protect the innocent — yes, these were all part of it. That was why he did it, because he had a talent, and he knew he had a duty to put that talent to good use.

But there was something else, too. Above all else, Holmes wanted to understand. Not just the criminal mind, but the mind in general — what made people tick, what made them human.

The whole thing hangs together only because of two huge coincidences, and I wouldn’t mind if they were fun…but instead they’re just there because otherwise there’s no plot, and the plot there is barely warrants even this degree of effort. If you told me that Christopher had an idea for how this was going to go, started writing it, and then found out that his contract wasn’t being extended beyond two books, I’d believe you. He did some really good work in The Ghost Line, and his robo-detective trilogy starting with Made to Kill (2015) is loads of fun, but his heart’s not in this and it shows.

All told, then, this is a disappointing final visit to the Elementary universe, but thankfully the show remains and has delights galore to offer. It’s a shame no-one has, like with Monk (2002-09), exploited the potential of the show — with its fast-moving plots, sudden reversals, entertaining setups, and superb character dynamics — into a series of novels, because the original literary heritage of Holmes shows that the written word can treat him well when done properly. I guess we’ll just have to console ourselves with the plethora of Holmes-adjacent literature published over the years, and keep striving to find more that has the fun it should with the concept.

~

Elementary recommendations on The Invisible Event: