![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Few people are as surprised as me at how much I’ve enjoyed the opening novels of S.S. van Dine’s career. They’re not fair play detection of the sort I’d like, but as an example of rigorous police work alongside an amateur dilettante they’re swiftly-plotted, lightly-written, and a very pleasing way to pass a few hours. And the fourth in the series, The Bishop Murder Case (1929), improves on the previous three in the matter of the killer not being frankly bloody obvious well before the halfway stage. Sure, you have to swallow a few coincidences, but, meh, where would classic detection be without that? Did anyone ever complain that Hercule Poirot or Perry Mason always happened to be on the scene of a murder? Think of what we’d have missed! Kick back and enjoy, that’s what I say.

The murder this time around is not that of a bishop, but instead of promising archer Joseph Cochrane Robin — not, thankfully, known as ‘Cock’, but nevertheless found with an arrow in his chest having just been hanging out with a love rival with an aptly relevant name. Echoes are found in the famous nursery rhyme, and a note pointing this out is sent to the New York papers, signed THE BISHOP. And so it begins.

“So it’s a real murder mystery, is it — with a corpse, and clews, and all the trappings? May I be entrusted with the tale?”

As before, District Attorney John F.-X. Markham brings in man-of-all-trades Philo Vance, and the two banter back and forth while murders echoing the theme of this first, with notes sent to the papers after each one, occur regularly and Vance insists that psychology is the only way to get to the root of things. This is, of course, not my first Vance’s rodeo, and I was pretty well-prepared for what was going on here, and as a fan of the man’s career to date I was pleased that this unfolded along more or less the expected pattern.

Van Dine isn’t content to merely repeat himself, however, with more work going into the ancillary characters this time — mostly consisting of a set of mathematicians and chess fanatics who, despite their common interest, are kept distinct through consistent portrayal of their attitudes. From the tolerant benevolence of Professor Dillard, around whose house so much of the slaughter centres, to the confrontational hunchback Drukker whose “mind is like a furnace that’s burning his body up”, and his melodramatic elderly mother who is fatally obsessed with the wrong she feels she did him in his youth, Van Dine is to be commended on the clarity of the people herein. I’ll remember them far more than anyone beyond the repeating characters who featured in the earlier books, and not just because of Vance’s lengthy and amusing categorisation of mathematicians.

There’s also the university lecturer Sigurd Arnesson, who, in order to test his theory that “mathematics is the basis of all truth however far removed from scholastic abstractions”, asks to be included in the facts of the investigation so that he might construct an equation that will identify the murderer. I’ve seen this elsewhere talked about as if Arnesson is in competition with Vance, paving the way for the sort of ‘duel of detectives’ that most series try to work in at some point — c.f The Murder on the Links (1923) by Agatha Christie, The Eight of Swords (1934) by John Dickson Carr, and countless others. In truth, nothing really comes of this, Vance and Arnesson on very friendly terms throughout, and so it’s an odd narrative choice to introduce the conceit and do so little with it, implying that maybe even Van Dine himself wasn’t sure about it.

“There’s far too much emotion in the world. Passion is not going to solve this case. Cerebration is our only hope. Let us be calm and thoughtful.”

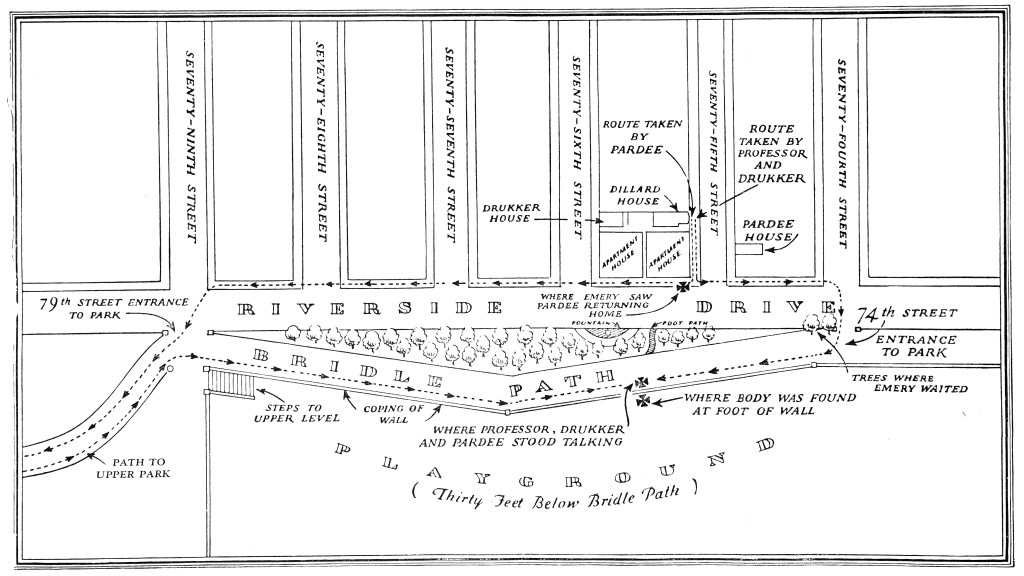

Once again, the solution is reached by wonky psychology and a complete absence of any actual clues, furthering my appreciation of Ellery Queen taking this as their model, because for all its success there is that very noticeable absence at the heart of these books. Markham remains stoic, Van Dine makes an amusing narrator — the footnotes remain entirely irrelevant to the plot, but crucial to enjoying the fun — and there’s something new in the denouement, I’ll give Van Dine that…even if I do wish he’d follow his own damn rules and actually include some evidence to point the reader to the guilty party for once. Also, thanks to Sergio’s review, I know that my Fawcett Gold Medal edition pictured above is missing this map, which is a shame if hardly crucial:

All told, I continue to enjoy Van Dine, almost because of his shortcomings where clewing is concerned. A swift, intelligent, archly-communicated time that will veer suddenly across three lanes of traffic to deliver a terminal surprise is precisely what I’m after when I pick up these books now, and to get that makes me very happy. If the books fall a little short, I can at least understand why they were so popular in their day, and I look forward to spending more time with Vance & Co. in 2026 and beyond.

~

S.S. van Dine on The Invisible Event

1. The Benson Murder Case (1926)

2. The ‘Canary’ Murder Case (1927)

3. The Greene Murder Case (1928)

4. The Bishop Murder Case (1929)

This might be just above Greene as my favorite SSVD even if it doesn’t quite capture the sense of dread and impending doom that its predecessor does. And as far as I am aware it’s the first detective novel to have the crime(s) structured around nursery rhymes!

Excited to hear your thoughts on Scarab whenever you get to that, my estimation of it has grown a bit since I read it earlier this year.

LikeLike

It has advantages over Greene, I agree. I still think my favourite might be Canary, despite the flaws within it as a mystery. But it’s a thin line between these first four, which really do maintain a very consistent standard.

I can see how someone who didn’t like his style could grow weary of Van Dine and Vance very quickly, but for someone like me who finds it all rather charming it’s a real delight to pick these up and find them to be so fresh and invigorating. Let’s see how long that continues…

LikeLike

So glad this went well for you Jim, really am. Cheers me up no end!

LikeLike

There’s hope for me yet, eh?

LikeLike

I read this a couple of years ago and bounced off it a bit. But then, I’d pretty well-absorbed the whole “Van Dine is bad” canard, which didn’t help! It’s interesting and maybe if I reread it with fresh eyes I’d get more out of it. You’re right, it’s not really a traditional fair-play whodunit at all. I remember wishing he’d done more with the nursery rhyme plot; it’s well integrated with the first murder, with multiple layers with how the suspects correspond with the rhyme, and then felt weaker with the latter ones.

(ROT13: Gubhtu sbe nyy zl pbzcynvaf, nf n uhznavgvrf znwbe, V zhfg fbyrzayl abq va nterrzrag jvgu Ina Qvar’f whqtrzrag ba zngurzngvpvnaf.)

LikeLike

It’s very easy to absorb accepted wisdom, especially in a small community where a couple of people saying something makes it as good as canon. I was guilty of this with Freeman Wills Crofts, and readers of this blog will know how that turned out when I eventually decided to challenge the assumed consensus.

I wasn’t dissimilar with Van Dine — it felt like I had to swallow a lot of doubt to pick up Benson (despite reading Kennel years ago, I remembered nothing about it) — and he works for me, much to my delight. But nothing’s for everyone, and I agree that the nursery rhyme could be better integrated; as a piece of imagination, though, it’s a very enjoyable jaunt.

As for mathematicians…no comment 🙂

LikeLike

I read this ages ago in an obscure, badly dated Dutch translation that kept referring to the murders by the archaic term “treurspel.” The first few times added some old-timey quaintness to the story, but after a few chapters, I wanted to beat the translator to death with his own typewriter. And poor Van Dine. He basically invented a new trope, murders set to nursery rhymes like lyrics, only to be outdone by nearly everyone who tried their hands at it.

LikeLike

Yes, Christie pretty much perfected this ten years later, and had a good go in a few other cases, too. Who else wrote good murders based around a nursery rhyme? My mind blanks after The Dame…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course your mind blanks!!!!

“There was an old woman who lived in a shoe . . .”

LikeLike

Oh. Them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like these. I really liked Greene and Bishop when I was younger, and the others in the first 6, though not as much.

Be warned the quality falls off a cliff after Scarab.

LikeLike

Yes, I hear the back straight is pretty tough; we’ll cross that bridge when we stumble over it, wishing the torment would end 🙂

LikeLike