We’ve had some serious detection this week already, so time for pulpy thrills!

I do not know how, when, or where The Rose Bath Riddle (1933) by Anthony Rud came to my attention, but the same could be said of about twenty books that I have eBay alerts set up for. Sure, this one has an entry in Adey — we’ll get to that in due course — but what are the chances of me plucking one title at random out of that wonderful reference work? Not zero, sure, given that I’ve been known to browse the possibilities on offer therein, but I’d be surprised if my original awareness came from there.

However I found it, The Rose Bath Riddle will hopefully not be my last encounter with Rud, because, while derivative and in many ways little more than a Shilling Shocker, it is well written, luridly memorable, and slick enough to imply that a good time could easily be found in the other works from his mind. Don’t rush out and spend your next mortgage payment on a copy, but if you share my weakness for pulpy, loosely-plotted, fun shenanigans, there’s much here to enjoy.

Amidst the wealthy enclave of Long Island, the investor/financier/businessman — I’m really not sure how to describe him — Simon Corlaes would appear to be the wealthiest and most fabulous, as betokened by the glorious party he throws at his rambling house to celebrate the, he says, end of the Depression and a return to profit and glorious financial stability. His aggressively ebullient spirit is checked, however, when upon returning to his private apartments he finds his loyal valet murdered by a blow to the head…the first, little though he knows it, of six or seven — I lost count — deaths that will occur in the mansion over the next twelve hours.

Fortunately, Corlaes knows the esteemed private detective J.C.K. ‘Jigger’ Masters, and immediately runs to him with the job of saving his, Simon’s, life — elder Corlaes brother Alfred having been murdered several months before, and this new murder perhaps a continuation of that. And so Simon and Masters return to the mansion where the party remains in full swing and, well, a lot more people die, with Masters and the police foxed at every turn.

I don’t know quite how to do justice to this, because it’s an odd proposition: for the first couple of chapters I honestly had no idea what was going on, with murder discovered, a beautiful woman visiting a dodgy pawn shop-owner, and Simon’s almost-adopted son Marshall intervening on her behalf. And, to be honest, it didn’t bother me one jot: clearly Rud believed in the characters and the setup, and I liked that he didn’t parade endless people in front of us just so we could get them fixed in our mind — or, more likely, forget we were ever told who they were — before getting on with the plot. Dive in, trust that things will become clear, and more fun is to be had.

What did it matter to any of them that a valet whom few of them had ever seen, had died mysteriously? These were people of importance. Or, if they were not really important, they wished to seem so. What did Lieutenant Connor expect to do? Put them through a third degree, perhaps strangle them or break their necks the way the Bristol police had done with a robbery suspect a few years earlier?

The police are already on the scene, for reasons best left to the reader to discover, and so the report of the murder confuses the trail a little and means it’s longer than usual before any response is made. And, when they find Masters already engaged and keen to take an active role…

Masters had no standing in [this case] as far as the law was concerned, yet in Essex County they were proud of this detective. Connor knew him personally, and had the tingle of something close to hero-worship along his spine whenever he was fortunate enough to work in conjunction with Masters.

…so that’s nice. Thus everyone works together, people keep dying, and Masters — not really anything to report about him, except a strong sense of moral duty (“Masters had the interest of his new client at heart. Despising the man had nothing to do with a conscientious performance on the detective’s part.”) — is increasingly confounded as every new development seems to result in a dead or badly beaten body. Honestly, it’s just a lot of fun, and even lays one obscenely blatant clue for the reader to pass over where the matter of guilt is concerned — though whether this is Rud’s legerdemain or simply the bald statement accidentally dropped in something that’s been speedily written I’ll leave to the reader to decide.

The text positively ripples with subtle touches (“That blue isn’t the first uniform you’ve worn, I take it!”), sharp little character descriptions (“…a quiet little man who looked like a bankrupt stockbroker resigned to clipping hedges for a living…”), and some lovely visual writing (“On the dead white of her cheeks two angry splotches of unshaded color showed like strawberry jam on a tablecloth.”). There’s also a pleasing sense of Masters as an intelligent man, with some scientific principles thrown around meaningfully that thankfully in no way recalls Craig Kennedy, showing that American Pulp writing could at least feel intelligent at times.

Masters is a likeable enough central presence, surrounded by a cornucopia of assistants who don’t quite measure up to his hopes — the portly Gildersleeve, one of many people rightly feeling wronged by the unscrupulous Corlaes, being my favourite — and wondering, when not obsessing on the possibilities of there being more than one killer to account for the slaughter, if one of the suspects might, should they prove innocent, make a good companion for later cases. I love this human element to him, so much better than a detective falling in love with a suspect, and it’s exploited well throughout, even as the madness deepens.

The rose bath of the title concerns Corlaes’s elaborate toilet facilities, including a shower which has “twenty or more spray nozzles which sent water upon the bather’s body not only from above but from all sides”. It is someone stepping into this and being frozen to death that earns the book its aforementioned entry in Adey, but, come now, it’s hardly impossible stuff and, more than likely, the solution will have occurred to you before the end of this sentence. Yes, it’s odd; yes, it’s garish; yes, it’s gruesome; yes, it’s unexpected; but an impossible crime? No, Bob, not by a long shot.

That answer is fun and pulpy — you’d never get it in a straight novel of detection, and that’s a shame — and the novel around it is always fun without really feeling like it’s doing anything else that’s new or notable (also, anyone who asserts that “no one but a Japanese could bathe with comfort in water at such [scalding] temperature[s]!” needs to talk to at least three of my ex-girlfriends). The writing hits some great notes at times (“Probably even murderers had their home lives and their personable traits, when not actually engaged in their grim avocation.”) and, all told, this could certainly be taken as a superior example of the type it represents, should you feel encouraged to track it down.

The reader is warmed…!

~

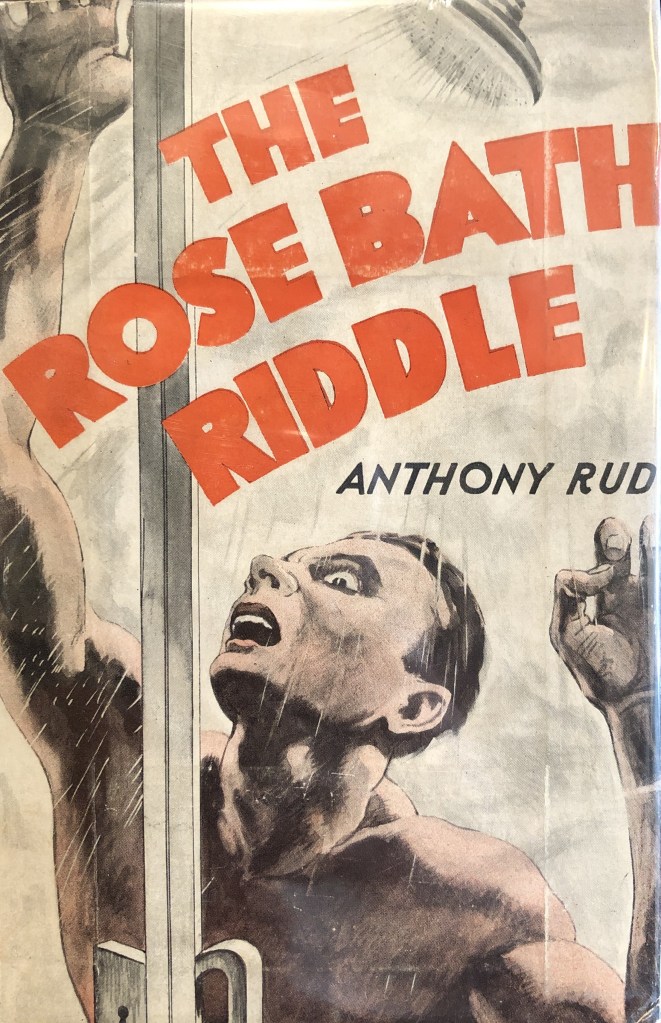

This title has recently been published as part of the Argosy Library in the edition pictured here, but I’m not sure whether it’s the same text as the Macaulay hardcover version I read. I know the book version of Murder on the Way! (1935) by Theodore Roscoe was very different from the version published in the Argosy (under, admittedly, a different title, A Grave Must Be Deep), so it wouldn’t be without precedent that a text was rewritten in some way before its publication as a novel. So if the above makes you eager to rush out and look for this, and you stumble over the edition shown on the left here, well, beware: that might not be what I read.