Today is the tenth Bodies from the Library Conference, at which, until other considerations intervened, I was due to present on the topic of inverted mysteries. And you can bet I would at some point have talked about Six Against the Yard (1936), in which six crime writers put their ‘perfect murder’ on paper and ex-CID man Superintendent Cornish picked holes in their plans.

I seized this with avidity upon its republication in the paperback edition above about 2014 or so, but clearly it didn’t make the strongest impression, as I had to go out and get another copy to write about it now. I remember enjoying the rigour — which I now know to be characteristic — of Freeman Wills Crofts’ effort, and rereading Dorothy L. Sayers’ ‘Blood Sacrifice’ in Final Acts [ss] (2022) got me thinking that I should try this collection a second time…and so here we are.

Furthermore, I seem to remember that poor ex-Superintendent Cornish had something of a thankless task, given that he could hardly go “Yup, they’d totally get away with that” and therefore set a great many would-be murderers on the path to committing a multitude of undetectable homicides. So how does this collection stack up at second visit? Let’s find out…

We begin with ‘It Didn’t Work Out’, in which a parallel universe Margery Allingham who performs in burlesque and revue shows watches her friend Louie marry a clearly unsuitable man…

He was an undersized, flashy little object with so much side you wondered he didn’t fall over.

…who goes on to undermine Louie’s career, abuse her, and generally turn into “a monstrous deformity that was dragging her to death”. When a shot at redemption come for Louie, our narrator knows there’s nothing for it but to kill her husband…and lays the foundations well, even admitting to the moment of his murder as if it was born from panic rather than design.

Cornish, titling his rebuff ‘Would the Murderess Tell?’, acknowledges the “diabolically ingenious” nature of the crime, laying rather more stress on the risk of being overlooked — that hardly matters, since our killer has already “admitted” to what happened — and a nebulous waft of a suggestion of “fingerprints which suggested that the…account of the tragedy was incorrect”.

There’s a slightly confused moment where Cornish seems to think that the story Allingham has written is diegetic and so could be found by the police, but he rallies for an interesting psychological argument that, if not entirely convincing, at least opens up the possibilities for discovery. Murder, Cornish reminds us, continues in real life rather than stopping at the final page of an artfully-constructed story and, in fairness, we none of us know how the pressures of continued existence may play upon us.

I can well believe now that I gave away my original copy of this book just to get ‘The Fallen Idol’ by Ronald Knox out of my house. While occasionally as dry in tone as you’d expect…

In the recent coup d’état — I beg its pardon, the recent Liberation…

…this story of the murder of the military leader of a fictional country is ohmygod so circuitous and tedious, and doesn’t play the game by hiding its murderer among a positive fusillade of activity, leaving it up to Cornish to solve, which isn’t the point. A fault on the detective’s part does not a perfect crime make.

Poor Cornish does what he can in ‘Murder in Uniform’, but if he honestly read this all the way through then he’s done more than most people who encounter it will. Between this and his contribution to The Floating Admiral (1931), I’m becoming more convinced that Knox’s sole notable contribution to the Golden Age was his Decalogue, and even then, because he couldn’t simply write a straightforward sentence, he managed to screw things up.

Of course, you couldn’t undertake something like this without involving the genre’s gameplayer-in-chief, Anthony Berkeley, and with ‘The Policeman Only Taps Once’ he gives us American tough guy Eddie Tuffun, low on funds — though, heaven knows, he seems to spend a lot of money herein without earning any — and so marrying Myrtle Frumm, who, with “a face like the back view of a cab horse”, he imagines will be free with her money in gratitude.

This is pretty standard stuff until Berkeley reminds you that he’s one of the most fondly-regarded GAD writers, despite his relatively tiny output, for a reason. That this manuscript is diegetic there’s no doubt — talk herein of burning it seals that — and it ends with a lovely reversal that really does feel like the perfect murder…brewed under just the right circumstances to delight and baffle in equal measure.

‘…And Then Come the Handcuffs!’ says Cornish, outlining a not-too-specious series of arguments based, in fairness, around a character we know next to nothing about. The detail he goes into reminds me very much of one Inspector Joseph French, and it’s to be wondered if this might have been the starting point for my love of the Humdrum mystery that brings so much joy to my reading life to this day. Good work by the ex-copper.

‘Strange Death of Major Scallion’ (why no ‘The’?) remains the only work by Russell Thorndike I’ve read, and this slow gathering of the conditions required to seek murderous revenge on the eponymous, boorish, blackmailing relative has about it more than a tinge of horror — especially when you get to the victim’s death and realise how much our anonymous narrator has done to ensure he suffers.

Interesting to note the moral element of these stories, too: not just that the people in them wish to get away with murder, but that it matters that the victims are all deserving of their death. No-one just finds someone they don’t like and decides to dispatch with them. It speaks a lot to the game-playing element of Golden Age murder that we, the audience, are fine with knowing these minutely-planned deaths are going to occur so long as they people being killed are bastard enough.

Anyway, Cornish rebuts with ‘Detectives Sometimes Read’ and highlights the similarity here to what I believe might be one of Thorndike’s own novels — bit bloody cheeky, that, not even coming up with a new murder, Russell. Crucially, though, Cornish seizes upon the one element of the story which struck me as false, which makes me wonder if it was added purely so that there was something concrete to base an accusation of murder upon.

To Dorothy L. Sayers next and ‘Blood Sacrifice’ which, as noted above, was the motivation for reading this collection a second time. And trust Sayers to buck the trend: there’s nothing really unpleasant about Garrick Drury, the West End impresario who takes John Scales’s miserablist play Bitter Laurel and turns it into a heartstring-tugging hit. Scales just wishes it was closer to his original intention, is all, and arguably brings his unhappiness about by not reading the contract he signs.

Sayers bucks the trend, too, in this not really being a murder, since accident intervenes twice to put Drury at — and, well, through — death’s door. And Cornish agrees, his riposte entitled ‘They Wouldn’t Believe Him!’ and laying out his perspective in no uncertain terms: “I say this ‘perfect murder’ is not murder at all”.

Interesting to finally meet a supposedly ‘guilty’ character and have little sympathy for them, however. Boo-hoo, John Scales has no idea what the public will pay to see and so ends up making loads of money from the efforts of someone who knows this stuff better than him to make his frankly unappealing play much, much more appealing. God, he’s a pillock.

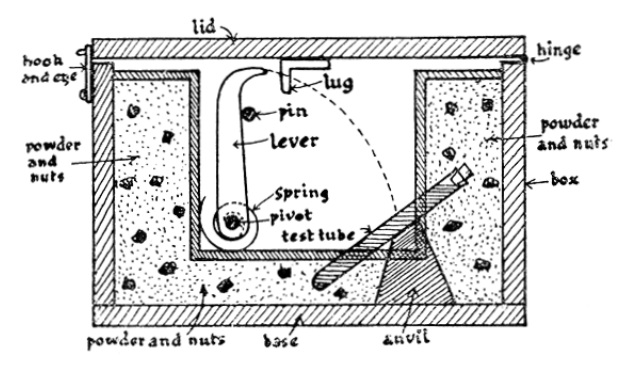

Finally, my good friend Freeman Wills Crofts, and ‘The Parcel’, which sees yet another blackmailer pulling rather too insistently at the hand that sustains him and paying the price. It’s amazing to think how much casual knowledge of murderous Chemistry there seems to have been in the populace in the 1930s, but that aside this is an enjoyable little tale that benefits from another ingenious murder trap from Crofts’ terrifyingly fertile mind.

‘The Motive Shows the Man’ says Cornish, doing a spectacular job in an initial piece of reasoning here, but then going on a few flights of possibility that somewhat weaken the brilliance of that first deduction, even acknowledging it himself: “Am I making things too easy for the detective by imagining all these possibilities?”. Still, this is easily the longest investigative outline in the book, so Cornish is at least aware of the difficulties Crofts has presented him with, and his exploration of how to extricate himself from these difficulties is intelligent, well-reasoned, and done in good spirit; Joseph French would be delighted.

What, then, of Six Against the Yard?

Honestly, I remembered it more positively than this. Sayers’ story is superbly written, but doesn’t fulfil the brief; Thorndike’s is really more of a borderline horror tale, Knox isn’t playing the game — so wipe out 50% of the contents straight away. I also remember Crofts’ story being more watertight than it turns out, but, given that good man’s strong moral inclinations, I suppose it would be somewhat counterintuitive to provide, to the paying public, an actual perfect murder.

The thing that comes through most for me on this second read is the personality and intelligence of Cornish — all credit to him for rising to the challenge, and for showing how assiduously and intelligently the art of detection can be applied (he’s certainly more believable than was poor Superintendent Walter Hambrook, who took on a similar, more thankless task the following year with Crofts’ Found Floating (1937)). One gets the impression that Cornish would be a great man to just sit down and chat with, on all manner of subjects, and it’s a shame that the GADisphere didn’t see more of him.

A Happy Bodies 2025 to all who are celebrating today!

I really enjoyed this collection and playing referee in my review, which ended with Cornish beating the Detection Club 4-2. You’re right it’s a shame we didn’t get to see more of Cornish. I think he would have some interesting and insightful things to say about the Humdrum mystery.

LikeLike

Ah, I wasn’t able to visit the Library this year either… next year, hopefully.

I think I was less generous to Cornish in successfully “catching” the killers in my review, but he’s a good writer and a thoughtful and observant reader.

No idea what Knox was thinking on this one. I get what he was thinking with the bit in The Floating Admiral, but that doesn’t mean it was a good idea (perhaps as a memo to the upcoming writers rather than forcing it on the poor readers…). Since I think Solved by Inspection is also pretty bad, that leaves The Three Taps – which I actually think is pretty delightful (and available on Gutenburg).

LikeLike

I gave up on Knox’s Footsteps by the Lock, so it’s good to know there’s a book out there you rate. Maybe I’ll find some joy in him yet, but history is not on his side…

LikeLike

While I liked “Solved by Inspection”, I had mixed feelings about Knox’s “The Three Taps”, which I just finished. As in “Solved by Inspection”, the puzzle is clever in “The Three Taps”. Unfortunately the middle 100+ pages sagged horribly with nothing much happening. I almost set the book aside out of boredom. To be fair, the last forty pages did pick up the pace nicely and I liked the solution, but overall I cannot recommend the “The Three Taps”.

LikeLike

Yeah, I think I’m happy to leave Knox’s fiction to others for the foreseeable future; he doesn’t inspire confidence in what I’ve read so far, and there’s so much else to read in the genre first.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this when I read it! Sayers was apparently really pissed with Cornish’s demolition of her mystery, and while I thought the story was great it’s impossible to disagree with him. She tried to be so clever about leaving no trace of the murder that as she erased the things that could leave clues she left no actual murder at all.

I will say though, as something of a Sherlockian I have to also pay tribute to Knox semi-accidentally inventing Sherlockian/Holmesian higher criticism! Sure, he may have been TRYING to use Sherlock Holmes analysis as a way to take down biblical higher criticism, but who can blame generations of canon fans for taking his analogies and using them as a launchpad into something much more fun.

LikeLike