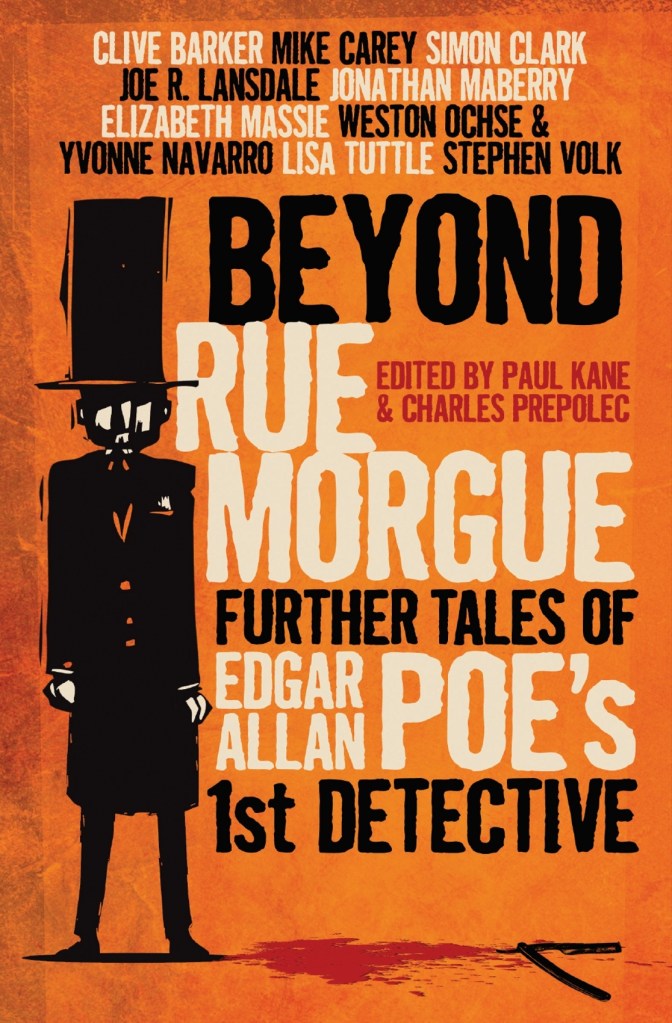

I have an undeniable fondness for the work of Edgar Allan Poe, having looked at his tales of ratiocination on this blog as well as written a novel inspired by one of his most famous stories. So Beyond Rue Morgue [ss] (2013), a collection of stories edited by Paul Kane and Charles Prepolec purporting to extend the career of Poe’s unfathomably influential detective C. Auguste Dupin, was certainly an intriguing find.

Containing eight new stories, plus one from 1984 included, the cynic might suggest, to get a famous name on the cover, this collection covers a range of possible cases for Dupin and his descendants from the abecedarian to the ghoulish and ghostly. My interest is much keener where tales of ratiocination are concerned, but let’s try and give everything a fair go as we pick through and see how much care has been taken here with the work of the Grandfather of the Detective Story.

We start with Poe’s original Dupin story, ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841), which I’ve read countless times and dissected at length here, so forgive me if I pass over it an onto the new material. I just thought you might like to know that it is included for those yet to experience it…though why you’d be picking up this collection with no knowledge of the story which inspired it is beyond me. But, anyhoo. And, look, I can understand why they didn’t include ‘The Mystery of Marie Roget’ (1842), but to also not include the magisterial ‘The Purloined Letter’ (1844) is a criminal oversight.

First new story ‘The Sons of Tammany’ (2013) by Mike Carey concerns the murder of 20 men working on the new Brooklyn Bridge when Dupin is in New York in 1870 for uncertain reasons and being shown around by newspaper cartoonist Thomas Nast. The mystery here hardly requires Dupin’s expertise, but Carey writes well…

[T]here was a lot of shouting and shoving of the kind that normally signals something unusual has happened, and — undeterred by that past tense — people are jostling to line up in its wake.

…and manages some good imagery (candle-clutching workers gathering around the dead bodies “like they were about to burst into a Christmas carol”) even if the most compelling part of the plot is left rather hand-wavey at the end. It doesn’t need to be a Dupin story, but it is and you can’t complain too much about it; neither, though, can you get too excited.

A quick online search tells me that Simon Clark is an author best known for horror, but ‘The Unfathomed Darkness’ (2013) is a decidedly earthly tale. Concerning at first the apparent impossibility of a dead body in the middle of unmarked snow, with a nearby row of footprints beginning and ending near no houses or obstacles, Dupin is quick to explain this away and Clark then builds on this setup with some lovely imagery (“A lady clad in pure white stood on a branch, high in a tree.”).

It’s not the most ratiocinatory story you’ll ever read, but I cannot deny that it proves very enjoyable (if a little talky…) on its way to a surprisingly effective climax. However, if you’re going to invoke the name of such an important character in detective fiction, I would hope that the solid and well-reasoned deductions in the early stage would be the very least the character does in that line, not the totality of it. I would, though, very much like to read more by Clark on this evidence.

‘The Weight of a Dead Man’ (2013) by Weston Ochse and Yvonne Navarro is a cowboy story set in 1895 with Dupin’s grandson as a Pinkerton detective. It concerns a missing painting, some missing women, and a Masonic blood cult, and devolves into a shootout with minimal detection along the way. I could believe it’s a good example of its type, but I did not care for it.

‘The Vanishing Assassin’ (2013) by Jonathan Maberry is very good indeed, and if its “line of bloody footprints [that] vanished mid-stride and were not seen again” is resolved without much fanfare, the reasoning that goes into the explanation is superb. Maberry really does capture the sense of ratiocination that underlines the Dupin stories and, while no-one has strictly tried to pastiche Poe yet, he has an impressive tone at times:

“The evidence we collect are elements of circumstance and a predisposition of mind that not only lacks clarity and is likely fatigued, but which is also shaped into a vessel of belief because of the macabre atmosphere.”

The cultural background to the events herein is fabulous, and really well-deployed, too. Maberry is another writer primarily known for his horror fiction, and, damn, that’s a shame, because I’d read a whole book of mystery stories by him on this evidence.

The fact that ‘The Gruesome Affair of the Electric Blue Lightning’ (2013) by Joe R. Lansdale contains a skybeam, the Necronomicon, an intelligent ape, and a mad scientist from Frankenstein Castle means you’ll get an idea of what direction it heads. It’s well-written (“G– solves most of his crimes by accident, confession, or by beating his suspect until he will admit to having started the French Revolution…”) and doubtless a good example of its type, but, like the cowboy story above, not really of interest to me.

The Rear Window (1954)-esque setup of ‘From Darkness, Emerged, Returned’ (2013) by Elizabeth Massie sees Molly Dupin, the housebound great-granddaughter of our Chevalier, trying to figure out who has murdered the delivery boy she had fallen in love with from afar. When Dupin comes to her in a dream, she is moved to look at the possible motivations for the people she sees moving around the neighbourhood.

There’s one particularly heart-breaking development in this, but in order to keep the suspense high Massie has to resort to a few unlikely developments, throws in an apparent clue which doesn’t end up applying to the solution (and, no, it’s not a red herring), and then resolves it all with an answer that requires you reject the core tenet of the whole thing. A very nice idea, this, but a few more drafts needed.

My caution was aroused when ‘After the End’ (2013) by Lisa Tuttle begins with the note “with apologies to E.A. Poe”, and sure enough this spends a lot of time telling us that Dupin did lots of clever thinking on his way to catching a murderer, but never shows us what any of that thinking was. Then the story continues, invoking spiritualism as an actual thing that works, its eventual thrust painfully evident and not worth the effort of pursuing.

Final new story ‘The Purloined Face’ (2013) by Stephen Volk is the longest in here, and mixes the brew somewhat, being a Sherlock Holmes pastiche — narrated by a young Holmes himself — with the detective being Poe, who has escaped to Europe and taken up residence under the name of his famous detective. It’s sort of a reimagining of The Phantom of the Opera (1910) but is about four times too long — like other Holmes pastiches of my recent acquaintance — and is resolved by the sort of grim realism modern writers feel the need to insert into historical mysteries to the benefit of no-one.

Finally, ‘New Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1984) by Clive Barker, which does a thing I hate: make out that an author’s work is only the result of them being told the story by another party, rather than that they came up with it themselves (one of the Ed Hoch Sherlock Holmes stories did this with Erskine Childers, and it still bothers me). As a creative yourself, why would you call into question the work of someone in this way?

Here, ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ is true and was told to Poe by the cousin of the man who actually solved it, but that’s then cast aside for another story involving murder that goes to such an odd place I honestly can’t recommend it. Barker of course does good work with the unsettling and disturbing, but I came here for detection and that this certainly ain’t.

A top five? In a collection containing only ten stories? Sure, why not:

- ‘The Vanishing Assassin’ (2013) by Jonathan Maberry

- ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841) by Edgar Allan Poe

- ‘The Unfathomed Darkness’ (2013) by Simon Clark

- ‘From Darkness, Emerged, Returned’ (2013) by Elizabeth Massie

- ‘The Sons of Tammany’ (2013) by Mike Carey

Coming at these collections with the perspective of a classicist is proving to be something of a folly — c.f. the recent Ronald Knox-inspired collection from Crippen & Landru — but, even then, I can’t help but wonder why the thread of “new” Dupin stories was used here despite so few of the tales displaying any of the ratiocination Dupin is known for. Still, when it’s good — and Jonathan Maberry’s story is excellent — it shows the potential that exists, the spark that must surely have been the instigating act behind this collection.

It’s a shame more of the stories here don’t stick to that brief, because there’s some genuinely great work that could be done in imagining new cases for Dupin. Thankfully, the introduction mentions the stories in this exact vein written by Michael Harrison in the 1960s, so now all I need to do is track them down: anyone got a spare copy of The Exploits of the Chevalier Dupin (1968) I can borrow…?