![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

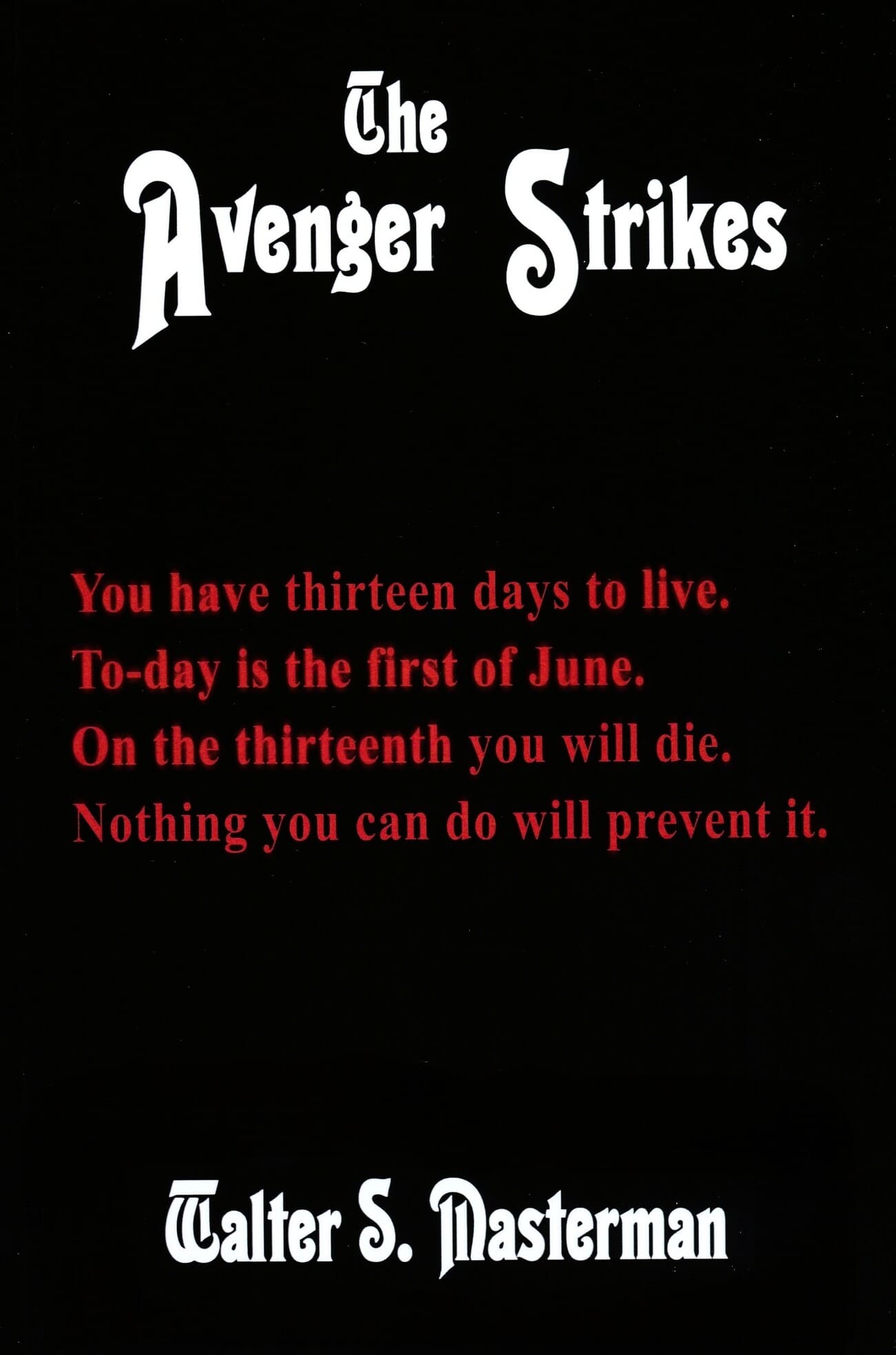

Not to split hairs, but if you receive an anonymous note on the 1st June telling you that you have thirteen days to live, the person threatening your life is going to kill you on 14th June, not the 13th. Either way, the wealthy George Hayling waits the best part of a week, receiving one note a day along similar lines — including a threat to poison his dog, which is duly carried out — before consulting the police. As luck would have it, he’s ushered into the office of Chief Inspector Floyd just as that worthy is completing a discussion with the esteemed Sir Arthur Sinclair, and something about Hayling’s case piques Sinclair’s interest. Only, with so little time remaining, can Sinclair keep the man alive?

You never know what you’re going to get with Walter S. Masterman, or how wildly he’s going to veer off the rails into unadulterated catastrophe, and it’s one of the things I most enjoy about reading him. The Avenger Strikes (1936), then, is a delight for how well-marshalled it proves to be, with Masterman keeping a firm hand on the tiller pretty much the whole way through, and showing no small amount of cleverness in some of his plotting. As a piece of pure Sturm und Drang it might even be the best book by him I’ve read to date — light on atmospherics, but well-plotted and with a few surprising developments that others in this game might not have deployed.

To Masterman’s credit, there are a couple fairly obvious answers as to who might be moved to threaten Hayling’s life that our author does not seek to mystify us with for too long. By about 15% of the way in, two possible plots, both of which the sort of thin fare you’d worry Masterman might just keep as a limp surprise for the penultimate chapter, have been thoroughly aired, and one of these is used for a pretty good piece of deduction by Sinclair in chapter VI. It’s a shame there aren’t more suspects — Sinclair is exaggerating when he claims at one point there are “up to six” — because the guilty party rather stands out come the clever machinations of the halfway point…but that, in a way, is also credit to the thoroughness with which Masterman constructs the second half of this.

An interesting seam runs through this, too, of Hayling being far from the sort of man whose life one would choose to save. He’s bullish, overbearing, cowardly, and generally unpleasant, and it’s a fun tweak to procedure to see this as the life at stake; Sinclair must try his best for the sake of mere professional pride, but at times, especially given Hayling’s well-documented craven streak…

The shadow of the grim enemy lay across his soul with the icy coldness of Dante’s lowest circle — that reserved for traitors.

…it’s understandably difficult to want to go to the efforts he does.

The second half of the narrative unfurls even more criminal activity, and avoids being too glib in its reasoning (“Some people seem to imagine that because a man is a criminal in one line he must be one in every other.”) in a way that was wonderful to see. Honestly, Masterman is a high-wire act of such intensity that I sat waiting for the house of cards to topple in on itself and…it didn’t happen! Good reasoning, some clever deductions, a neat piece of fair declaration to set up the denouement you know is coming — this was really well done, and Masterman deserves credit for keeping it together as tightly as he does.

Some good ideas — the winding forward of the clock, say, or the secret being guarded by an ex-serviceman and his wife — hold hands with some solidly impressive writing on the nature of justice, with Sinclair free to do as he likes and worry about the moral implications later (“A word from me and [a suspect’s] whole life is blighted, his family brought to ruin, and probably suicide for him. And yet what good would his arrest do except to satisfy intrinsic justice?”). It’s not quite Peter Wimsey crying on the morning of a criminal’s execution, but it’s fun to see a morally grey sleuth play with such a free hand, right the way up to the surprisingly moving conclusion of the whole skein.

You should not expect The Avenger Strikes to be a lost masterpiece, and you’ll enjoy it more if you have experience of Masterman’s tendency to veer at a moment’s notice into lanes of plotting that only a madman would consider, but as a solid and well-wrangled example of the detective novel, written at a time when the First World War was within painful memory and so needed to be written about with the tact shown herein, it has much to commend it. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that this has made my Walter S. Masterman experiment worth it, but I can’t deny being pleased at my perseverance paying off in this small way. Who knows what other delights await us…?

~

Walter S. Masterman on The Invisible Event

Featuring Chief Inspector Arthur Sinclair:

The Wrong Letter (1926)

The Curse of the Reckaviles, a.k.a. The Crime of the Reckaviles (1927)

The Mystery of Fifty-Two (1931)

The Nameless Crime (1932)

The Baddington Horror (1934)

The Rose of Death (1934)

Death Turns Traitor (1935)

The Avenger Strikes (1936)

The Secret of the Downs (1939)

Back from the Grave (1940)

Featuring Inspector Richard Selden:

The Bloodhounds Bay (1936)

The Border Line (1937)

Standalone:

The Perjured Alibi (1935)