It is no doubt fitting that the last Sherlock Holmes pastiche I read saw our Great Detective tackling a copycat of the Jack the Ripper killings in 1942, given that the next one I would go on to read would see him tackle the actual Ripper killings in 1888.

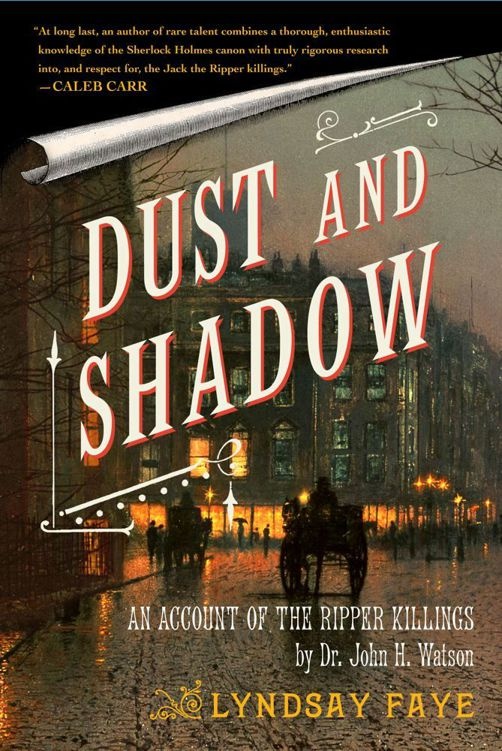

Back in January, I asked for recommendations of Sherlock Holmes pastiches, and first mentioned was two books by Lyndsay Faye — the novel Dust and Shadow (2009) and the short story collection The Whole Art of Detection [ss] (2017). I did some research and found out that Faye’s Holmesian pastiches are very highly rated, so figured this would be a good place to start a month of Tuesday posts on that exact topic. So, how did I fare?

I’ll be honest, I love the way Faye opens the book, after the almost-obligatory preface telling us that this is all super-secret and too shocking for society at the time, etc. Frankly, I’d like Sherlockian pastiche writers to do away with this — we get it, it’s a new story not published at the time of the original canon because you weren’t born in the mid 1800s — but the opening lines of chapter one are superb:

It has been argued by those who have so far flattered my attempts to chronicle the life and career of Mr. Sherlock Holmes as to approach them in a scholarly manner that I have often been remiss in the arena of precise chronology. While nodding to kindly meant excuses made for me in regards to hasty handwriting or careless literary agents, I must begin by confessing that my errors, however egregious, were entirely intentional.

It’s a confident start, to immediately dismiss one of the most commonly-stated complaints about the canon whilst simultaneously thumbing a nose at those who might take this sort of thing, y’know, a little too seriously. It’s also a good tone settler, confirming up front that the voice of this is going to more or less meet the expectations and hopes of the none-too-casual reader who is here looking for a continuation of the Great Detective’s career. And so we learn of a beastly murder, and that to be followed by another, and another…the career of Crimson Jack has started, and Holmes is swiftly brought into things.

Though, to be honest, I’m not sure how I feel about this melding of fiction and reality. Butcher all the fictional people you like and I’ll barely turn a hair, but you can’t get away from the fact that the Ripper’s victims were real people who really died, no doubt in agony and terror, and so blithely folding them into the world of fiction feels a little…not quite disrespectful, but at least not quite the done thing. We can at least be thankful that Faye doesn’t go Full Deconstruction and make Holmes himself is the Ripper — someone’s fucking done it, I’m sure, and that person should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves — but, if I’m honest, I felt a little uncomfortable with truth rubbing so damn closely against fiction.

Faye at least seems to get the details right, from my loose understanding of the Ripper case, and works in some good psychology (“Crimes of jealousy require a measure of regard for the victim.”), the like of which might not have gone amiss at the time, were such elements of detection in use. And she’s good at era-appropriate wrong-headedness, too (“[N]o native Englishman could ever have killed a poor woman so.”), even if, being that our author is American, I couldn’t help but see something like a smirk peeking around the edges of these small attacks on English snobbery. But, no, she’s playing with a straight bat — ha, another English idiom — and seems to be enjoying herself in the milieu, complete with references to “the affair of the second cellist” and “the incident involving Fenchurch the weaver and his now-infamous needle” that add to the lore in the most tantalising of ways.

What Faye, similar to Caleb Carr — from whom a laudatory quote on the cover — fails to get right, however, is the sheer pace of Doyle’s writing. I know not everyone’s a fan of The House of Silk (2011) by Anthony Horowitz, but I remember him saying that, essentially, the Holmes style was never really built to support a longer narrative, and so to make his book novel length he essentially came up with two plots and had them overlap in the middle. Faye doesn’t seem to appreciate this, and so her chapters meander, with about 60% of what’s involved being redundant and there simply to make the book novel length. Honestly, you can follow the plot just by reading the chapter titles, and some of them — like chapter five: ‘We Procure an Ally’ — achieve little more than they state and, gleeps, take an age in doing so.

It gets, well, boring.

If you have the patience for it, the book is undoubtedly well-written…

[I]t seemed an age had passed since we had first set foot into that terrible pen, open to the sky but closed off from every vestige of the human decency we had been raised to cherish.

…and Faye understands that, as a society, we have perhaps supped full enough with horrors not to be too moved by violence on the page and so writes about the Ripper’s desecrations with a careful and righteous air, but, honestly, this draaaaaags, and I found myself skipping ahead and not missing very much when I did, and as soon as I notice that about a book its hold on my attention is…numbered? And, after all this, the solution she offers is shocking only in the most basic of ways, and surely far from original — I’m not minutely-versed in Ripper lore, but I’ve read the broad strokes of what she suggests in at least a few other places before this. And while there are a few clever touches — the third murder (or maybe the second…I’m vague and not going back to find out) has a really clever idea at its core that is to be celebrated given the need to display fidelity with reality — I don’t think the destination warrants the journey.

Looking back through this now, I found the following which sums up my feelings pretty aptly:

Lestrade’s diligence commanded our respect even when his utter lack of imagination strained the independent investigator’s nerves.

There’s much to respect in Dust and Shadow, but it’s a book written with a complete forgetfulness of the need to entertain, and with, it feels, a lack of appreciation of what made Doyle’s original stories so popular and enduring. So my experiment has stumbled at the first hurdle — well, okay, about the twentieth hurdle, this being far from the first Holmes pastiche I’ve read — but this experience has at least clarified what I’m looking for in a successful pastiche. And I would absolutely read Faye’s Holmes short stories on this evidence, so expect them to follow in due course.

Next week: someone else’s turn…