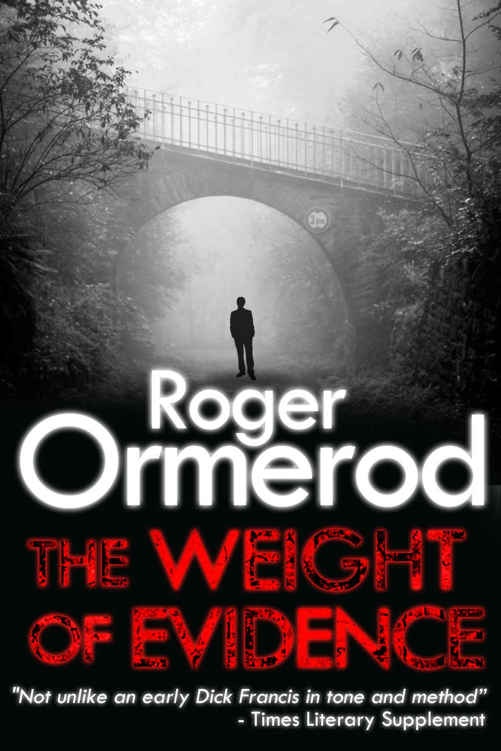

Having enjoyed-if-not-loved my first encounter with Roger Ormerod’s work, Time to Kill (1974), he’s hovered on the fringes of my awareness as someone I should get back to. So a timely recommendation for The Weight of Evidence (1978) sees us pick up again with David Mallin

Four years and ten books previously, Mallin had been a Detective Sergeant with the Birmingham police, but clearly something has happened in that interim since this opens with him now operating as a private investigator along with a partner, George Coe, who is also a former policeman. Mallin make reference to the events herein being the first case the two have taken on together, though whether it’s Mallin or Coe who’s new to this I was unable to determine. But, as first cases go, it’s a doozy, with an unpopular member of a construction crew vanishing from a tin shed that had been lowered in place over him with its door a mere six inches from the high fence that surrounds the building site.

The problem is made more intriguing by certain features — the shed was placed on a foundation of solid concrete, which our vanished man then fixed the shed onto thanks to bolts fixed in the concrete before the shed was lowered over him — not least of which is that there was a window our vainshee could have smashed to get out through but didn’t. So, why not? And how could he have disappeared in such a cast iron — well, poured concrete — classically locked room setup?

Wisely, Ormerod explores this setup thoroughly before revealing how it was achieved well before the halfway point, but the unravelling merely reveals a second impossible setup: a body found shot in a cellar that was bolted on the inside. Indications are that the body has been there for some 13 years, and George seems insistent that the shooting isn’t suicide and so must therefore be another impossibility to explain. George’s reasons aren’t exactly without flaw — the gun might have been clasped in the corpse’s missing hand and taken away when whoever opened the hatch went down into the cellar for whatever reason — but the book’s more fun if you don’t cavil too greatly (Mallin does enough of that for any sceptical reader, worry not). And, anyway, the fact of a more recent body possibly shot by the same gun proves problematic enough: because if the first body was suicide then the gun used to shoot the second one would have been left in a damp cellar for a decade and a half and would surely not be in any sort of utile condition.

In Ormerod’s favour, then, is an interesting setup which explains its first impossible mystery very intelligently (convenient luminol notwithstanding — surely it’s not that effective…) and then proceeds through the plot in a, yes, workmanlike but still very swift and arresting way. His characters are largely Types, but he has a good eye for memorable descriptions (“He was wearing a dented tin hat, from under which his hair sprouted like a wheat sheaf at sunset.”) and does a highly commendable job in keeping his focus on this core group of six or seven people, the various relationships always looping back around to add new layers and interpretations to events.

I also like the relationship between our narrator Mallin and George. Though you don’t get a great sense of them as people — late on, Mallin demonstrates an offhand familiarity with classical music that comes out of nowhere — there’s an easy, unspoken bond between them which is played for laughs at times (George “pulling in his belly in a way frightening to see” when trying to fit into a tight space, say) but runs somewhere closer to mutual respect, giving some credence to Mallin’s tolerance of George’s insistence that the second crime they’ve uncovered has this impossible aspect. So, as they barrel around an unnamed city (presumably still Birmingham) from stock location to stock location (flats! hotel! flats! building site! house! flats! — the budget for the TV show would have been quite manageable, one feels) they remain good company.

Counting against Ormerod is that sometimes — quite frequently, in fact — it can be very difficult to follow the thrust of the narrative’s developments, especially when he relies on dialogue. This is well-demonstrated in the following (apologies, slightly long) passage, in which Mallin is speaking to the police force’s firearms expert, Collison, without wishing to divulge that he, Mallin, is no longer a policeman and so does not have an inside line on the investigation:

“[Superintendent Meakin] hoped you weren’t too quick with those bullets. It makes things awkward,” I admitted.

“Quick? It only takes a few minutes.”

“I mean, with one of them in the body so long…”

“Beautifully preserved. Nickel-jacketted, you know.”

“But still, it seemed it could have caught a rib. Otherwise, a thirty-two, it should’ve gone right on through. The range would have been close.”

“Did he send you to ask these things?” said Collison with interest. “Is it me you’re querying — or him?”

“You’re the expert.”

“Then I’d advise you not to query Meakin. You don’t seem to realise that a lot of illegal weapons are loaded with very old cartridges. The charge deteriorates, you know. No — it hadn’t touched any bone. Perfectly marked.”

The shot that killed [the other body] had also failed to emerge. It was an uncomfortable similarity.

“The thing is,” I persisted. “Don’t want to be difficult, you understand. But if the charges can deteriorate, how about the gun itself?”

“If it’s well kept, I don’t see why…”

“A gun lying in a damp cellar for thirteen years?” I asked, feeling a fool.

“Who’s said that?”

George had said it. My partner, who’d go to his death still maintaining it. That’s who’d said it. “The suggestion has been made.”

“Does [Meakin] know?”

“It was he who suggested it.”

“Then he’s going senile. Can’t keep his mind off —”

“I’ll tell him what you said.”

“Edited, I hope.”

The upshot of this is that Mallin now knows that the two victims were shot with the same gun, but precisely how we’re supposed to know he divined that is, I’ll be honest, somewhat beyond me. This might, in part, be a deliberate ploy on Ormerod’s part, however, getting you used to Mallin making connections without the reader quite being able to hold onto his coattails, because it will prepare you for the series of closing revelations where our Porsche-driving P.I. simply suddenly knows how everything was done and why and…well, it’s a very good explanation indeed and makes superb and satisfying use of most of the events which have preceded it, but how he was able to figure it out is, once more, above my comprehension.

The Weight of the Evidence is to be celebrated for how it brings a pretty damn vintage-style plot that would have worked in 1937 and drops it almost fully-formed into the late-1970s, an era which, remember, probably had little time for rigorous, puzzling constructions. It’s not perfect — it sags a little in the middle, for one — but it’s an exciting discovery from an era that it would have been all too easy to overlook, and you can be damned sure that I’ll be getting back to Ormerod before too long. He wrote about 40 books, so how many great little puzzles are there still to enjoy?

“how many great little puzzles are there still to enjoy?”

I particularly enjoy When The Old Man Died, a unique locked-room mystery set-up in which the victim is found shot dead next to a clock that has clearly had its face destroyed and the hands tampered with. However, when the clock’s face was destroyed, the glass landed in front of the door, where it clearly remained undisturbed. In other words, the detective is sure someone tampered with the clock to fabricate an alibi — but unless the clock was destroyed from outside, it’s impossible to then leave the room after tampering with it. And if the clock was destroyed from without, then it’s impossible to get in and tamper with the clock. A true blue locked-room alibi in which the murder itself isn’t the locked-room problem — the act of tampering with the clock is.

Face Value is Ormerod’s best and probably one of the 10 — maybe even 5 best detective novels written after 1950 in my opinion. It is also a locked-room mystery.

More Dead Than Alive is Ormerod’s most classical effort, being the locked-room disappearance of a magician from the top of a tower in an old castle — very classical. The locked-room mystery’s solution is incredible, both in the sense that it has an insane degree of panache and boldness, and in the sense that it is LITERALLY not credible. It’s the type of solution to make you roll your eyes and go “that’s such bullshit”, and whether that’s in a good or bad way will depend entirely on your mood.

Happy reading, hope you keep enjoying Ormerod!

LikeLike

I really appreciate this rundown, thank-you. Now I’m torn between reading one that we already know to be pretty good, and forging out into the unknown titles like everyone else has done before me in the hope of uncovering some gold myself…

LikeLike

Just read ‘Face Value’ thanks to your recommendation and is terrific. As with the other one or two Ormerod’s I’ve read the characters are a bit cardboard and melodramatic but the murder plot is superb. Thanks for the heads-up

LikeLike

Another blogger who I follow is a an Ormerod fan and introduced me to his books. So far I have read “Face Value”, which was good, with four others on the big pile.

Don’t make the mistake that I did as “Face Value” is the UK title but was published in the US as “The Hanging Doll Murder”. I own both thinking they were different books, which they’re not.

LikeLike

It’s vexing when ghat happens.

I remember early on in my John Dickson Carr days finding Lord of the Sorcerers and thinking I’d come across something unknown to the list of titles I’d compiled…alas, it’s merely The Curse of the Bronze Lamp in new clothes. Not even a good book!

LikeLike

You can pay in installments if £1.99 is beyond your means in one go!

LikeLike